A hundred years after Farrago’s first print-run, it is no surprise some pundits have questioned if the near-legendary University of Melbourne student union newspaper is still revolutionary, or whether it has become redundant.

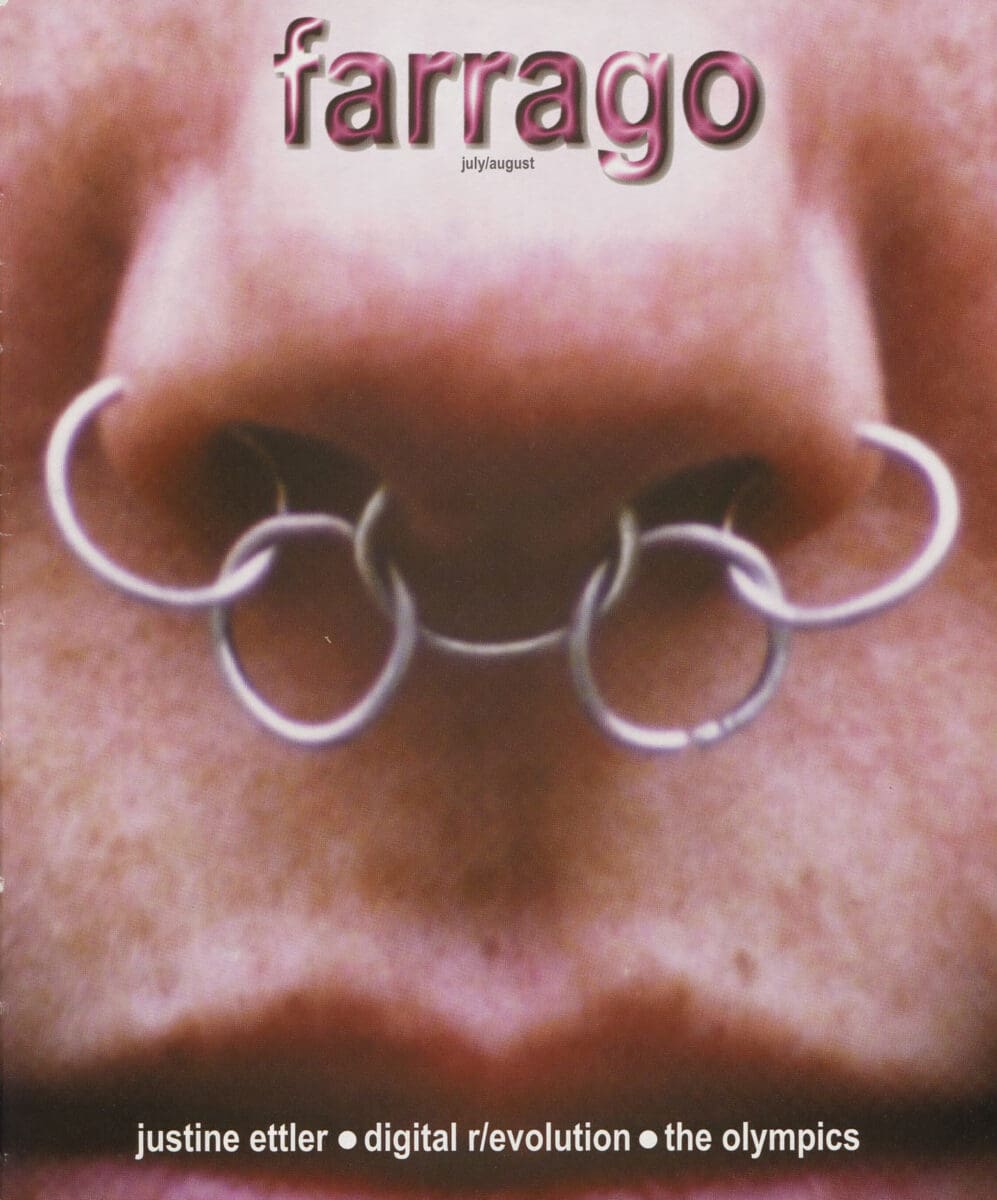

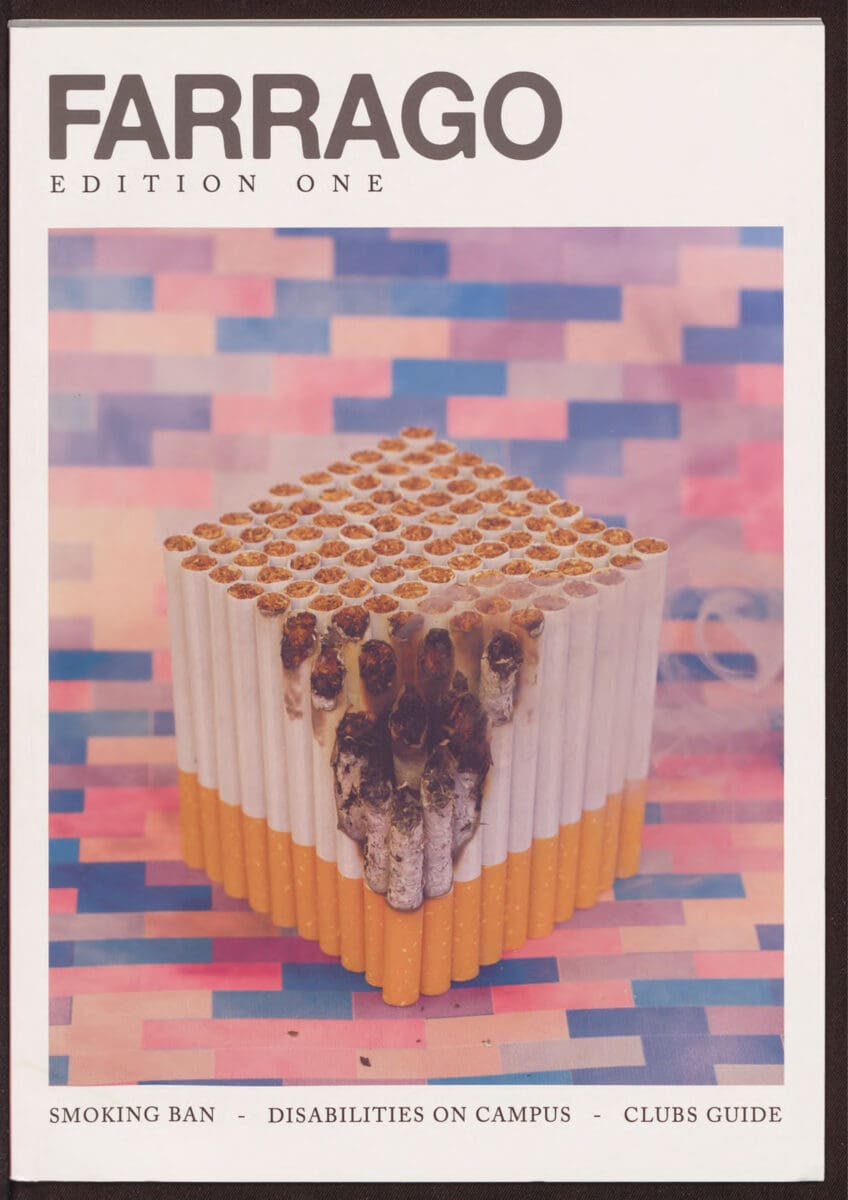

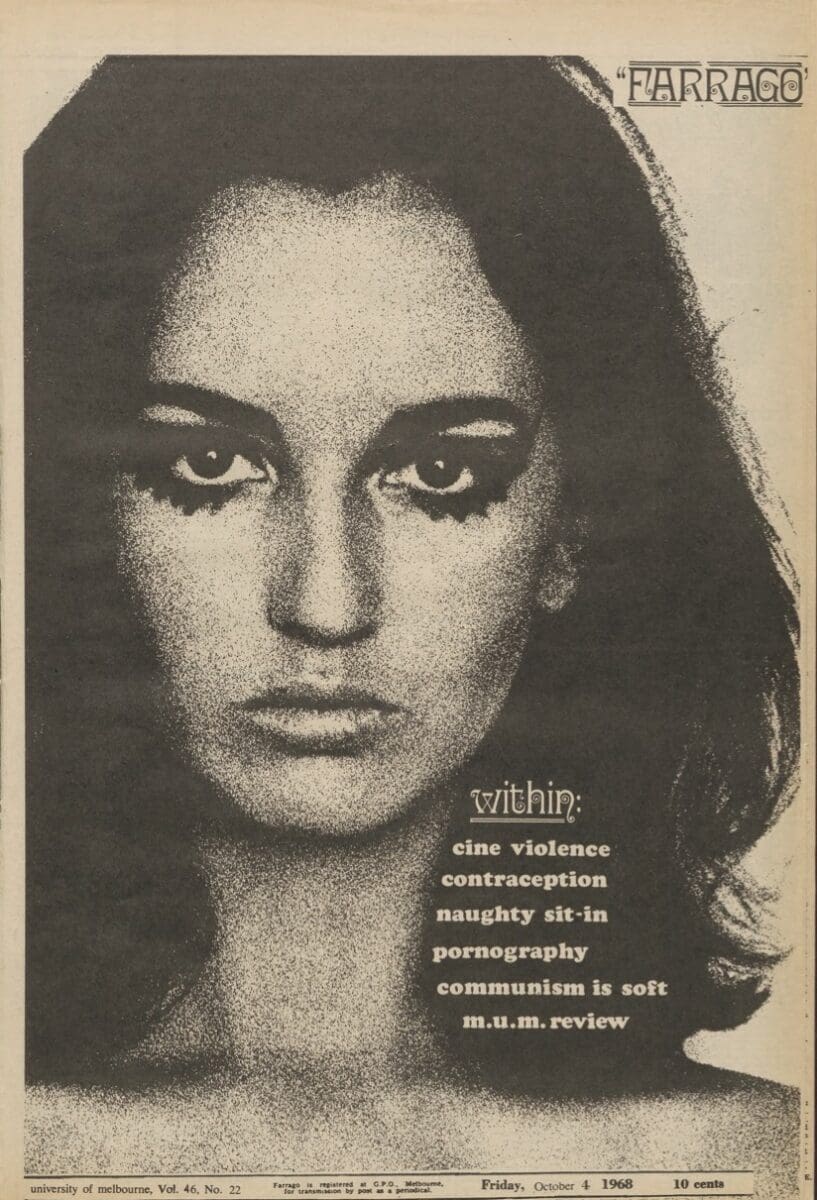

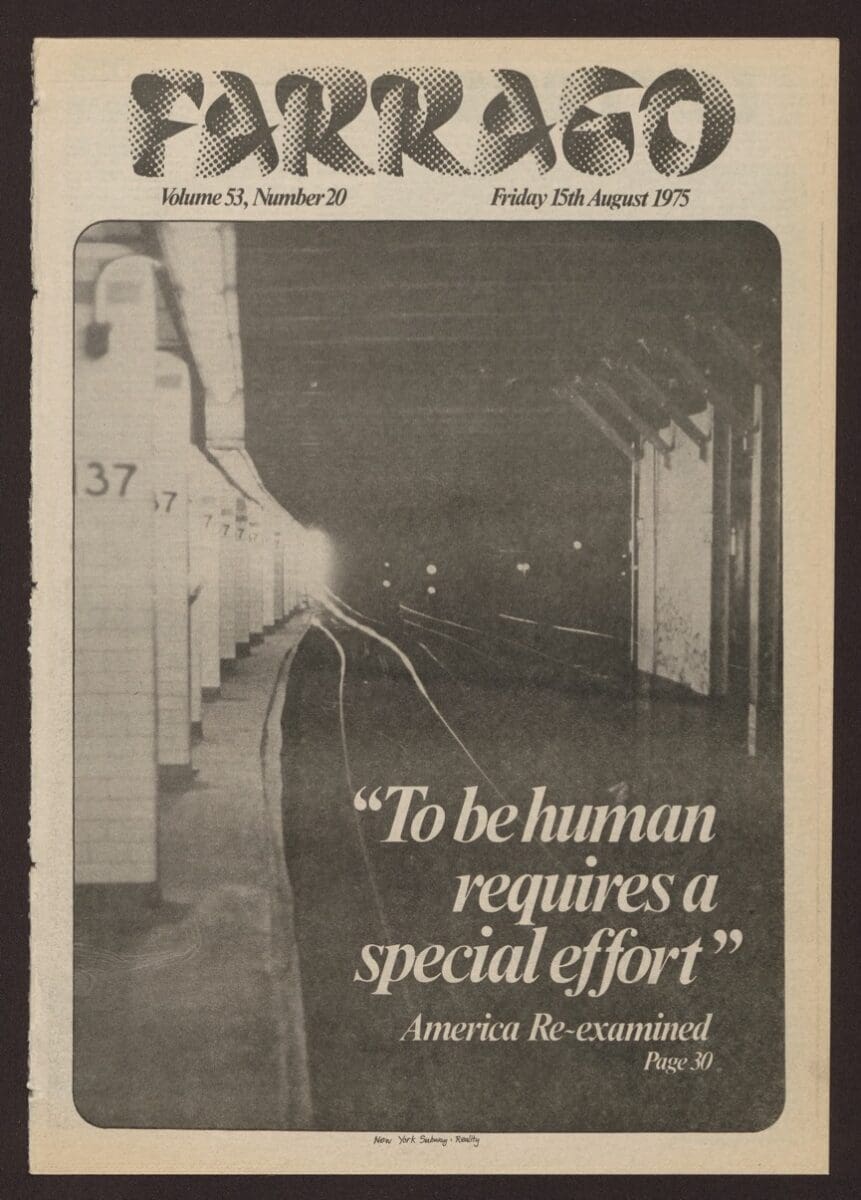

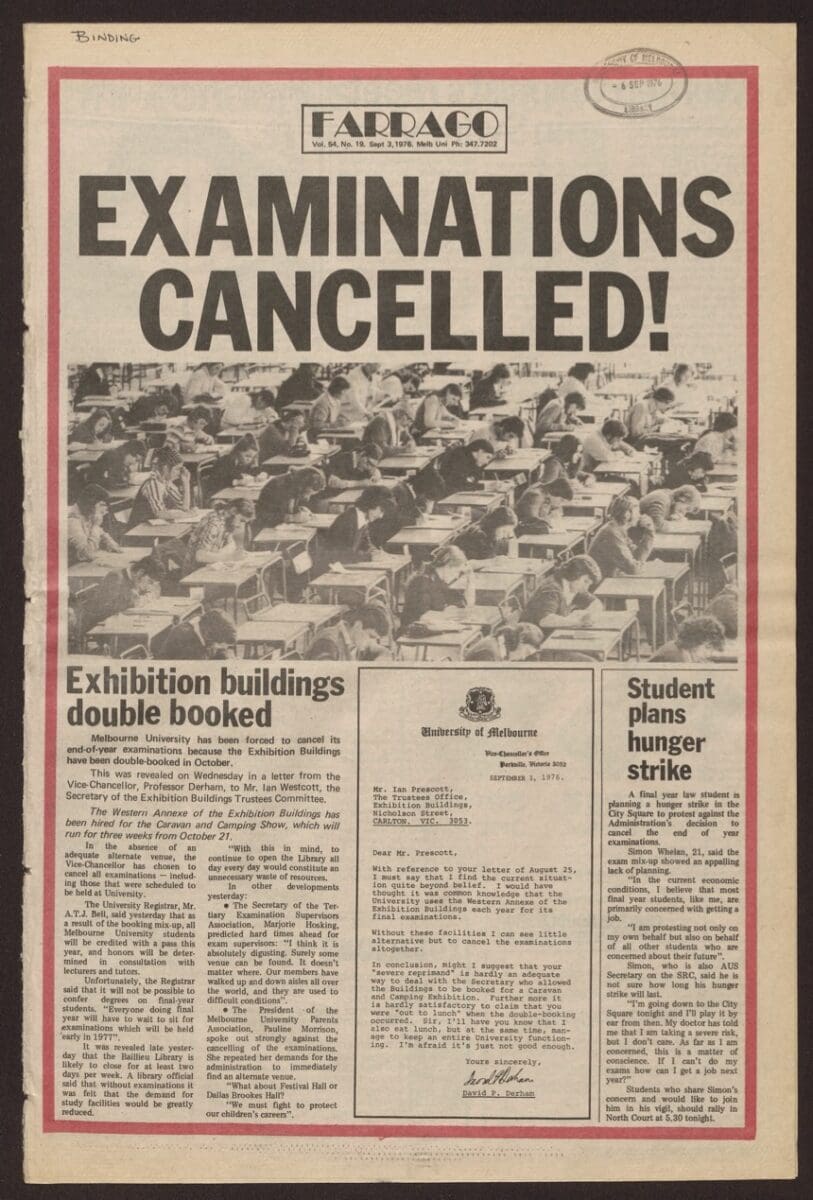

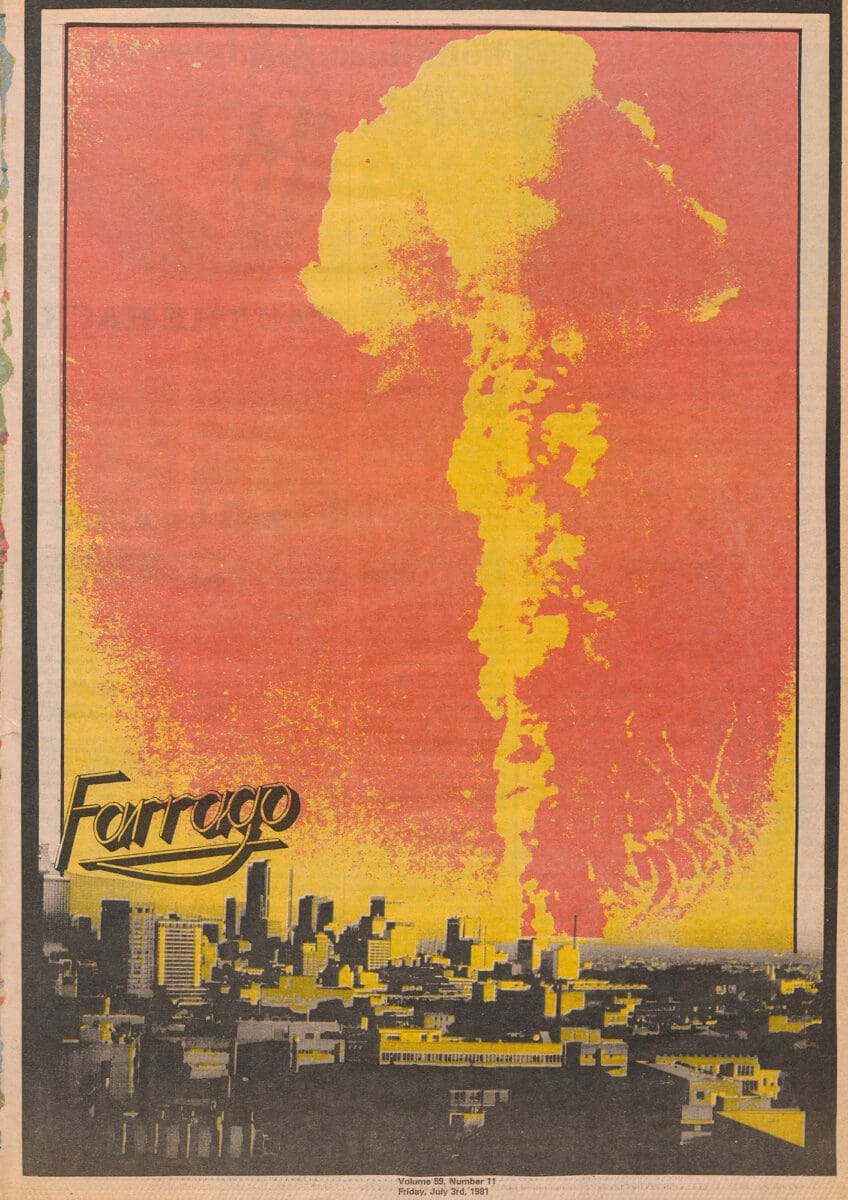

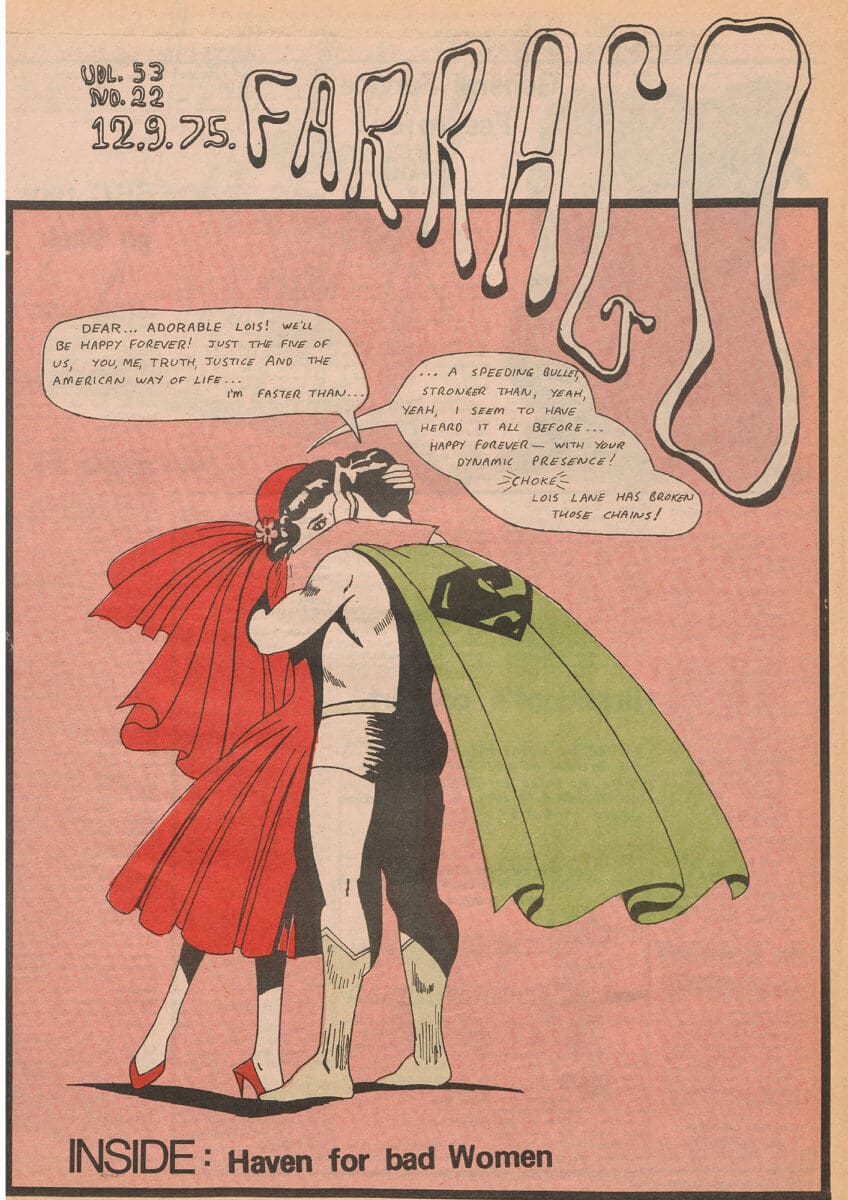

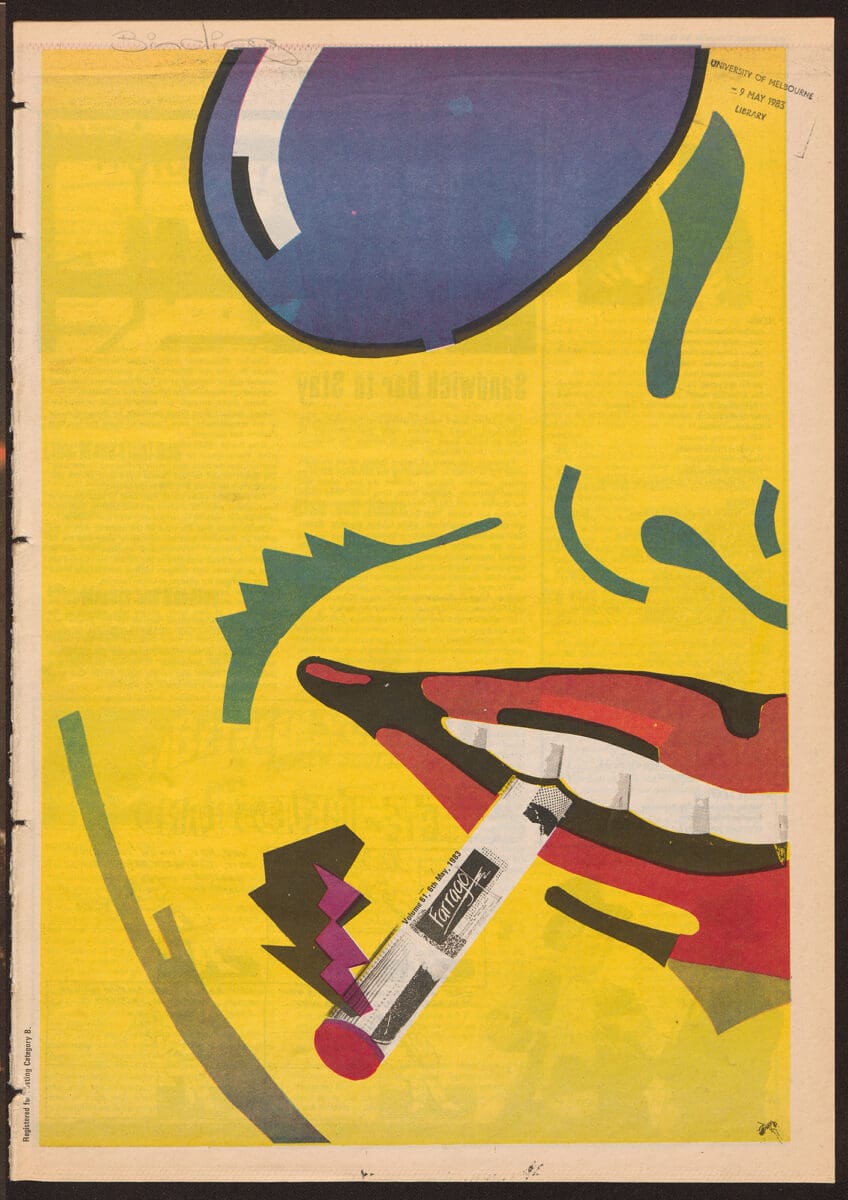

Flip through its decades of eye-grabbing front covers and the breadth of tone and content is extraordinary, ranging from trenchant activism to solid reportage, and from the compelling to the fashionable. Yet, always, there has been one unifying element: a proclivity for boldness.

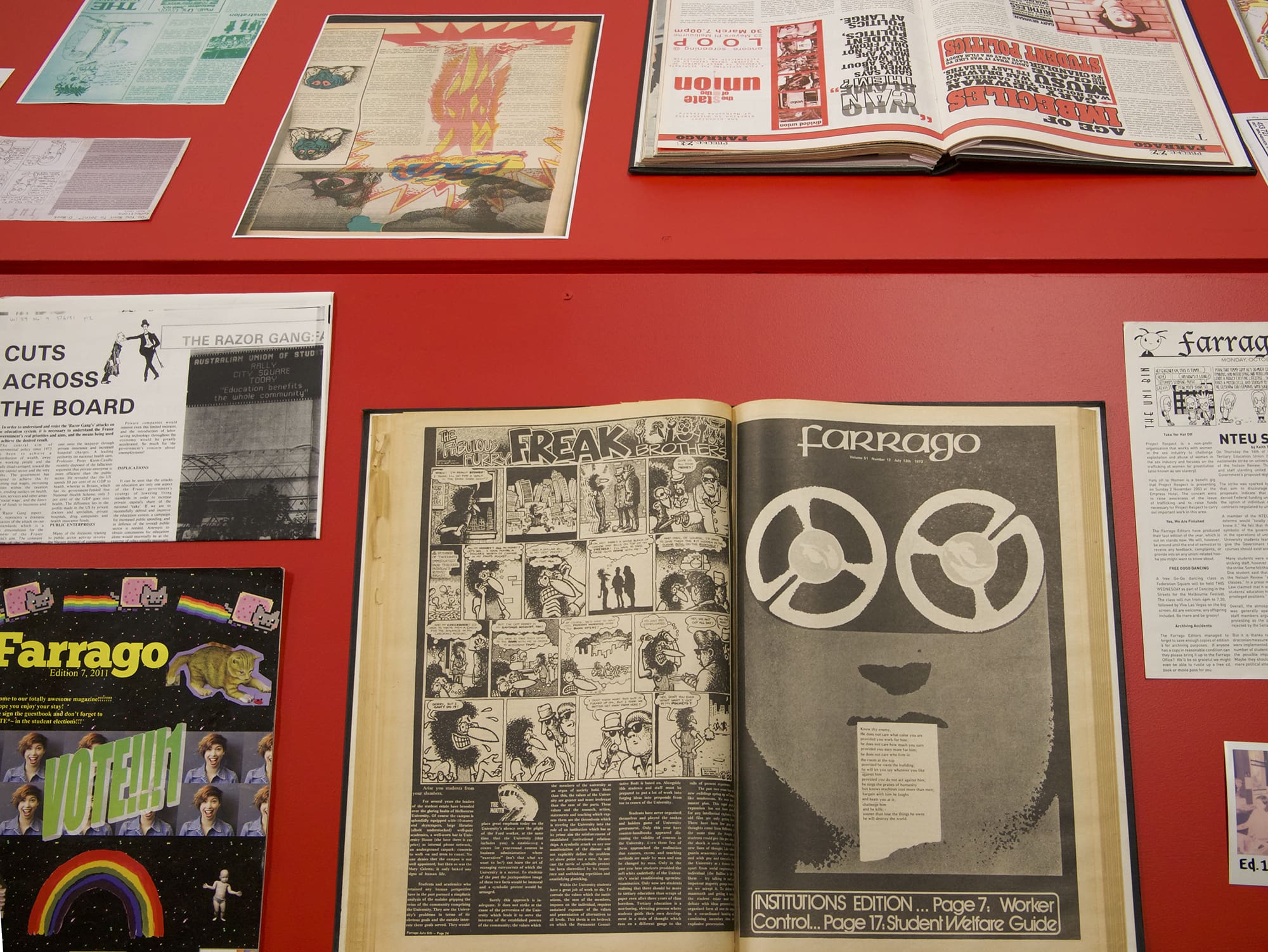

To mark its century of rousing up the Parkville campus, the exhibition Farrago 100 Years features many of those arrestingly designed covers, along with memorabilia and video footage. All of it begs the question: what is the secret to the fiery publication’s impressive longevity?

That might be down to the quality of its long rollcall of editors, many of whom have gone on to brilliant careers in publishing, as noted in a 2018 Farrago article titled Revolutionary or Redundant? Farrago Then and Now. Luminaries such as Christos Tsiolkas and Nam Le, along with historian Geoffrey Blainey, The Conversation’s editor-in-chief Misha Ketchell, lawyer Nicola Gobbo, writers/editors Kate Legge and Sally Whyte, and many others, have left their inky fingerprints on Farrago over the years.

The George Paton Gallery exhibition comes at a time when print publishing, especially in the arts, remains under severe pressure, most recently with the extremely unpopular decision by Melbourne University Press to close Meanjin, the revered literary quarterly that has been running for 85 years.

As Monash University media lecturer Ben Eltham wrote recently in The Conversation, if an institution as venerable and important as Meanjin can be killed off with the click of a mouse – there was no warning or consultation for staff—then “few cultural organisations in the country can feel safe.” Eltham also led a protest of hundreds of people—the sort of thing Farrago has always staunchly supported and publicised—outside the MUP offices, calling for the magazine to be saved.

Farrago, like Meanjin, is certainly a cultural institution, which is why the exhibition is divided into three broad brackets—a loose timeline is featured along one wall showing Farrago’s journalistic prowess and key news moments such as Vietnam War protests; an appraisal of its richly groundbreaking visual and design history graces another wall; and an engaging display of many issues of the magazine itself runs through a central area of the gallery.

Gallery director Channon Goodwin says the challenge within a modest-scaled venue has been to unpack such a lot of history represented by printed ephemera. “This goes back to its early days when Farrago was a newspaper-formatted weekly,” he says. “The exhibition allows us to navigate the visual aesthetic and physical form of the magazine and what that says about student journalism on campus.”

As he says, Farrago’s evolving format not only reflects changes in content and emphasis, but also developments in the world beyond. “Once, it was all about urgency, news and the issues around the university campus; it was a key news source.” This focus inevitably extended over time into broader political coverage, and its heyday of front-line picketing visuals from the 1960s and 1970s, when student unionism was famed for anti-war and feminist concerns.

“They are the things that have made up Australia’s socio-political history over the past hundred years, echoes of the sort of frontline engagement which are still obviously rippling down to this very moment.”

As Farrago moved towards more of a magazine-style by the 2000s, it began to grapple with the new, rapidly spreading social media landscape. “The question now is how does [Farrago] cover the urgent issues of the day when you have a million sources from where people get their news? It’s not a hot-off-the-press urgent news source anymore, but it does represent a more reflective engagement with the political issues of the day, and it also represents the diversity of voices which the magazine needs to service on campus.”

Farrago still serves up polemical journalism, arresting design and visuals, and retains its legacy of always featuring groundbreaking artwork, illustration and photography, Goodwin says. “With Meanjin having just been closed, and with stalwarts of the scene dwindling, it’s a really important question about how you keep these things alive, and why they should be kept alive,” he says.

Farrago 100 Years

George Paton Gallery, University of Melbourne, Parkville Campus

(Melbourne/Naarm)

18 September—10 October