Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Of the 65 European masterpieces on loan to Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art this winter, Titian’s circa 1550 painting Venus and Adonis is the work that affects QAGOMA director Chris Saines the most: “It’s almost like an opera in the way this story is told.”

Classical myth, when a goddess and an earthbound mortal unite, tends to end in tears, and so it seems fated as Venus clings to Adonis and implores him not to embark on a hunt, where a wild boar will charge him. Saines adores the work as a “rich and complete story” that is emotional and dramatic, while Titian’s “breadth and fluidity and looseness” in his brushwork “tell you there is a great genius in the making of this painting”.

The other works on loan include Caravaggio’s The Musicians, Rembrandt’s Flora and Vermeer’s Allegory of the Catholic Faith—but how does one even begin to edit 500 years of European masters into a representative 65 works? “That’s a little like saying, ‘How do you understand Western civilisation without reading the British Library?’” Saines laughs. “It is possible to encompass a big story arc with an exhibition like this.”

The exhibition is divided into three chapters: the development of the Renaissance through devotional imagery; into the Baroque; then right up to the early 20th century. Indisputably, European Masters from the Met is a serendipitous event for QAGOMA audiences: the exhibition has come about because the Met is renovating its European art galleries, and might not have been loaned to Australia otherwise.

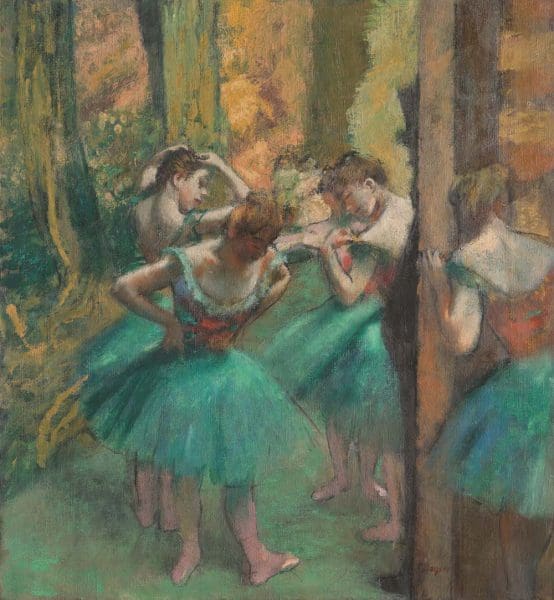

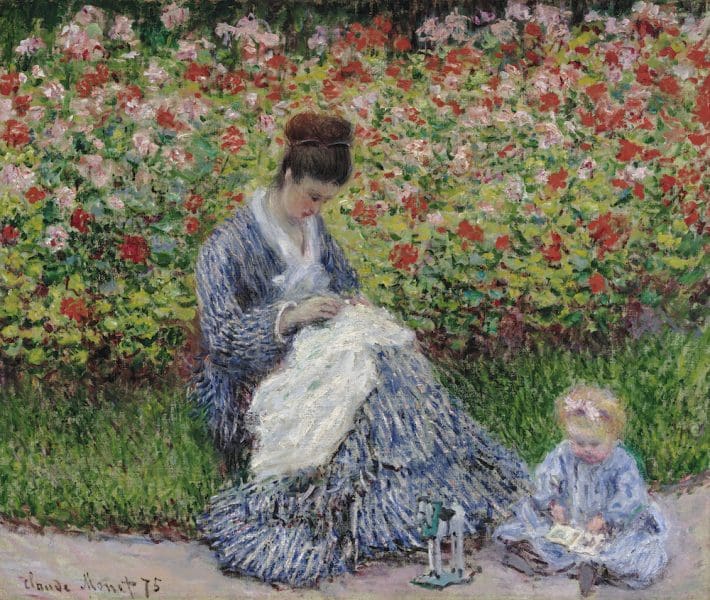

QAGOMA’s opening of this show in June coincided with the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) opening its French Impressionism exhibition direct from Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, with more than 100 works by the likes of Monet, Renoir and Pissarro. In addition, the NGV is showing Goya: Drawings from the Prada Museum, comprising more than 160 works on paper by Francisco Goya (1746-1828) and featuring 44 drawings on loan from the Prado Museum in Madrid.

Why do the European masters still resonate so widely for audiences? “These are paintings that have survived for hundreds of years,” says Saines. “The stories these paintings tell cause us to go back in time and consider the context in which the work was being made, whether it was the result of the rise of Catholicism, or whether it was an increasingly secular world such as the modern era.

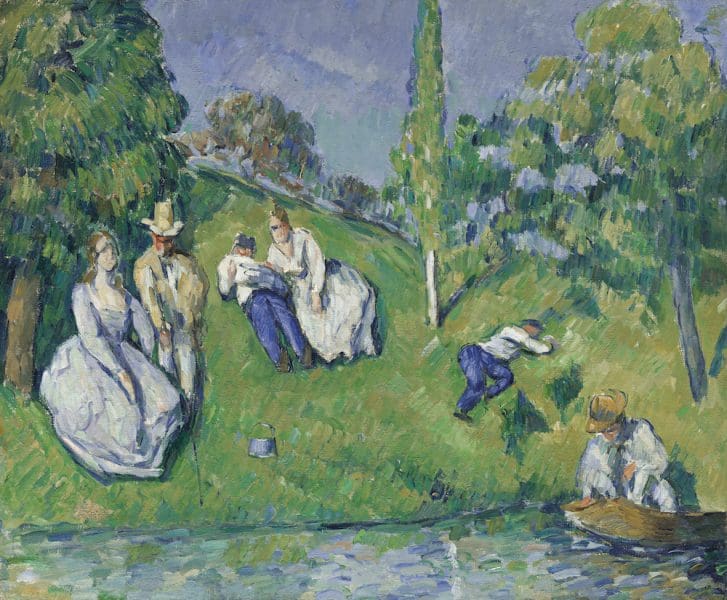

“When you see these stories bound together in one show, so often it’s artists looking back to artists who have preceded them. We’ve got two wonderful works in the show by [post-Impressionist] Cézanne, who looked back to [French Baroque] painter Nicolas Poussin, because he wanted to give painting that solidity of classical painting, as opposed to the flux and ephemerality of Impressionism, per se.”

The NGV’s curator of international art, Ted Gott, counters that the attraction of the Impressionist works is their “timeless beauty”. He says it is impossible to pinpoint what he is most excited about in the French Impressionism exhibition—although from the 19 Monet paintings, he nominates one of the Haystack series from 1890-91, as well as Renoir’s famous Dance at Bougival from 1883, which shows a couple dancing closely at an outdoor beer garden in summer on the outskirts of Paris.

“They were cutting edge artists at the time of what they were trying to do politically, in breaking away from the conservative exhibition system that was constraining them—but they also created works of art that were beautiful to behold and perennially enjoyable,” says Gott.

“I think that’s a large part of the continuing success: it’s one thing to be politically astute and groundbreaking as an avant-garde artist; it’s another thing to create works of art that are just so exquisite that they will forever be in the canon of humanity’s beauty.”

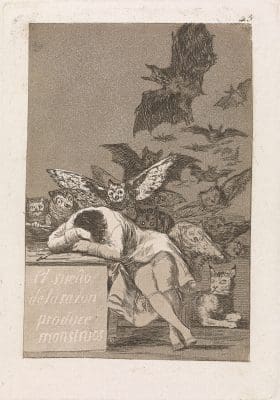

Story and mythology meanwhile are a big part of the legend of Goya’s work, ranging variously from his time in Madrid, his work as a court painter during the Peninsula War when the French Army invaded Spain in 1808, and then onto the later black paintings when he withdrew from public life.

Politically, Goya was a liberal angered by the Catholic hierarchy’s rejection of the 1812 Spanish Constitution and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1814. In 1793, Goya had suffered an undiagnosed illness, leading many to speculate about the impact of his resulting deafness on his art.

The NGV’s senior curator of prints and drawings, Cathy Leahy, says Goya found drawing “incredibly freeing, because he could give free rein to his imagination and his powers of invention”. These uncommissioned, private works show what Goya really thought about Spanish society, with pieces ranging from 1794 through the self-exile of his final years.

For Leahy, the work of European masters resonates “because that’s the canon of art history.” She continues: “They’re the artists written about the most or considered exemplars of a particular style or period. The work resonates in terms of its draughtsmanship or painterly qualities.”

Goya, meanwhile, continues to have relevance for many contemporary artists, says Leahy, being considered the “first modern artist” for exploring “the psyche and humanity’s inner world”. This begs the question: do such European masters offer audiences experiences and engagement that contemporary art cannot, as much as new art might echo their past achievements?

“Art is a continuum,” says Leahy, “and the very best art helps the viewer to reflect on universal themes. If you think about Rembrandt and love and the inter-relationships between people, just like good literature, good art gives one an entrée into ways in which the tenderness between a mother and a child, for example, is encapsulated in an image. “The masters can give you experience into earlier periods in a very direct way . . . They shine a light on a time in history.”

European Masters from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gallery of Modern Art

12 June–17 October

French Impressionism

National Gallery of Victoria

25 June–3 October

Goya: Drawings from the Prado Museum

National Gallery of Victoria

25 June–3 October