Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

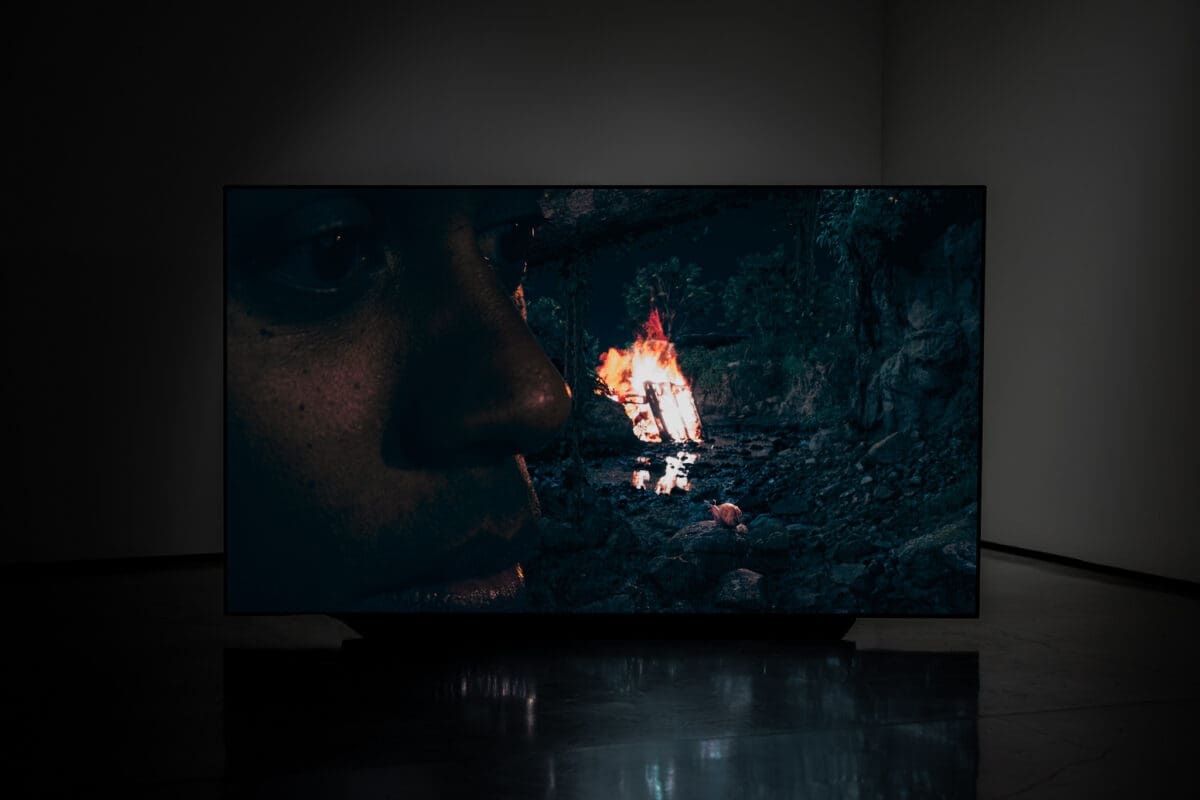

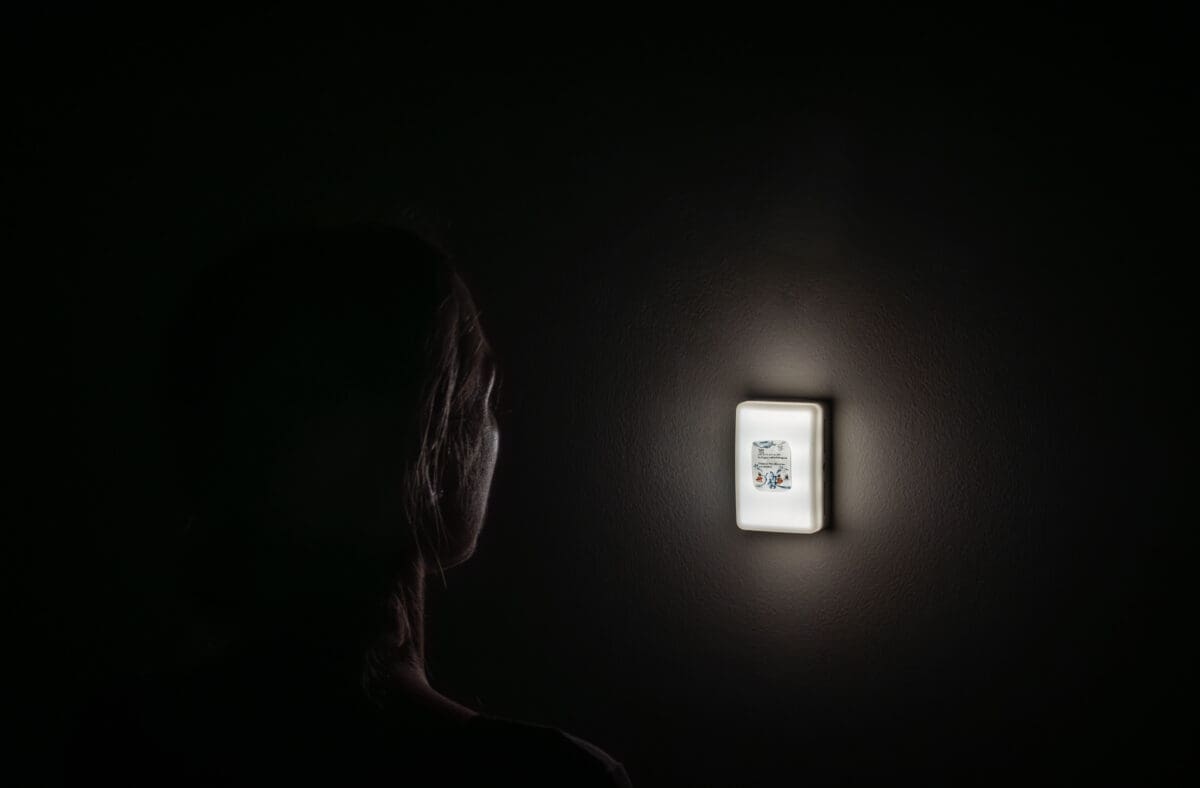

Entered through a heavy black curtain, the gallery is dark and its sparse layout is mirrored: two flatscreens crouch in opposite corners, separated by a large, central, double-sided projection. This spatial mirroring reiterates the content of the work itself—cyclical conversations between the artist and a snail; the trajectory of mineral extraction → manufacture → obsolescence, as objects re-enter landscape as shiny relics; political cycles of social progression followed by reactionary regression. Mounted on opposite walls is a pair of small, illuminated blocks: night lights. By the time I get around to the first one, it’s too bright to look at directly. It hasn’t taken long to acclimatise to the darkness.

Extinguishing Hope is an exhibition by Akil Ahamat at UTS Gallery, first staged through a West Space Commission in Melbourne in 2024 and curated by Sebastian Henry-Jones. It continues a project of worldbuilding that Ahamat has developed since 2019 through a series of interconnected works. With Dante’s Divine Comedy in mind (the inscription above the gates of Hell is generally translated to the English as: “abandon hope all ye who enter”), the exhibition title could be read as a dramatically grim statement: we’re not just abandoning hope as we enter Hell, but extinguishing it, perhaps as Earth itself becomes a hellscape.

There is little doubt that we are moving into dark times. At first it seems antithetical, but holding onto hope can be paradoxically harmful. Once we accept collapse, we can start to think about what comes next, rather than seeking transformation from institutions that will not, or cannot, change. In Ahamat’s proposed world, extinguishing hope is not a descent into stasis, but a propulsive force—letting go of hopeful but unhelpful fictions (like the idea—discussed in-depth in Melissa Ratliff’s catalogue essay—that hard work always delivers reward) can be generative. Perhaps it’s actually generous to put out the fire of hope, burn its fictions, and cover our tracks so that no one else repeats our mistakes.

Giving up things, and giving up on things—beliefs, relationships, plans—also makes room for new possibilities. In the world of Extinguishing Hope, the protagonist/artist is separated from the rest of humanity, but this enables them to connect with a non-human entity: the snail. Solitude, here, is not antithetical to belonging and intimacy. Instead, it opens up possibilities and connections.

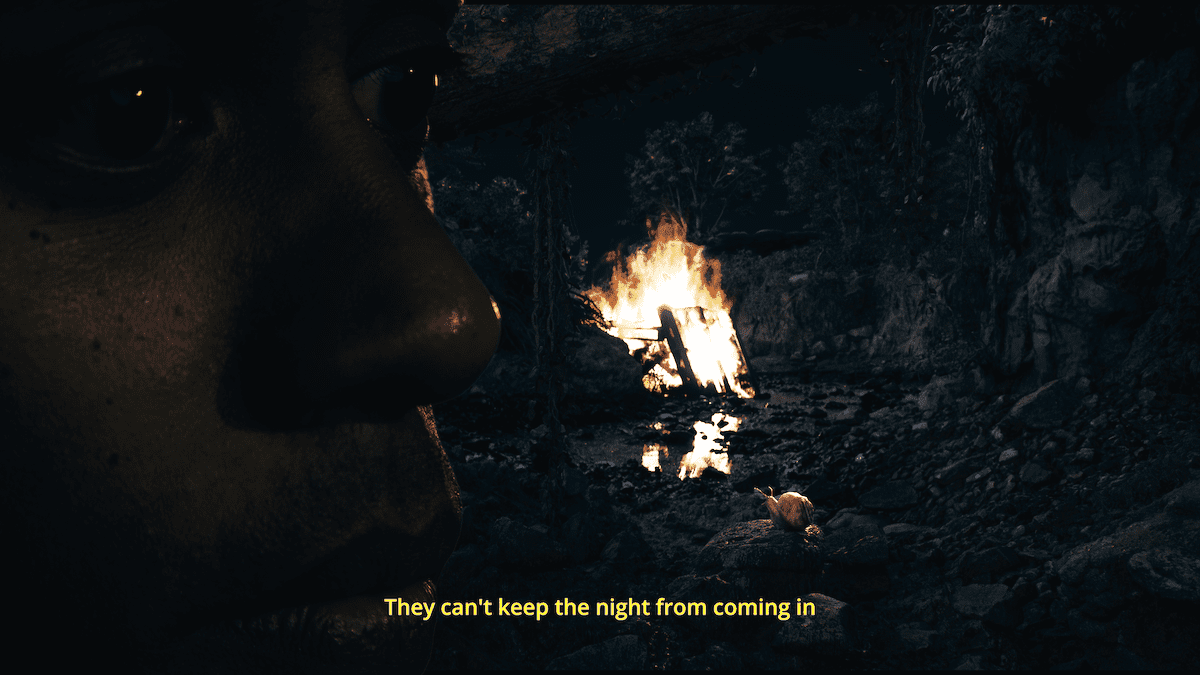

The conversation between artist and snail takes place in a rocky ravine within earshot of a large crowd. The artist’s voice is soft, gentle, almost plaintive, as if half-awoken from a dream. The snail’s voice is a close, wet, crackling squelch, like an excretion: a slimy aural artefact, subtitled in English. Ahamat evocatively describes their connection as a “fragile, intimate sonic space”. Listening to it is like hearing an alien (the snail) try to understand human behaviour by asking a human—but it landed on Ahamat, who has pretty unusual philosophies about what it means to be human.

Ahamat: “Promises don’t always mean something. They’re just something we make up to hold us together for another day”

“Like a story?”

“No. Stories always mean something. I guess promises do too. But you just don’t know if they’re fiction until later”

“So, it’s a story you have to be patient with?”

“Yeah, I guess it just slows things down a bit.”

Separated from the noisy, invisible crowd, Ahamat and the snail discuss promises, stories, miracles, visions, belief, and faith. They ask and answer a lot of questions in their intimate, looping conversations, but at their core they are asking: what do we do when we can’t trust what we see? And: how do we find each other in the dark?

Ahamat denies a singular reading of their work. They’ve painstakingly crafted a world using an open-source gaming engine, spending hundreds of hours alone in the process (they joke—I think—that ‘extinguishing hope’ describes the process by which the work was made). We are then invited into this constructed world, and from its language, mood, and visual cues, we can extrapolate and render meaning in any number of directions. This is our contribution to the work, to its world.

Like a snail, this work is slippery. If you try too hard to pin its meaning down, or attach a singular reading to it, it retreats. But it leaves looping traces; like a snail, it cannot hide its tracks. A generous publication accompanies the exhibition, and its cover is a bibliography—a meandering, glistening thread that leads us through a chain of divergent thinking, corralled into relation through the artist’s unfolding curiosities. The references are something solid to hold onto, a guide through the dark.

At some point in our conversation, Ahamat suggests that the key to being ok in the dark is to stop looking, and I think they’re right. We can’t see in the dark. Once we stop expending our energy on impossible feats, on fighting grim inevitabilities, maybe that’s when we reach out with our hands, and find each other.

Extinguishing Hope

Akil Ahamat

UTS Gallery

On now—19 May