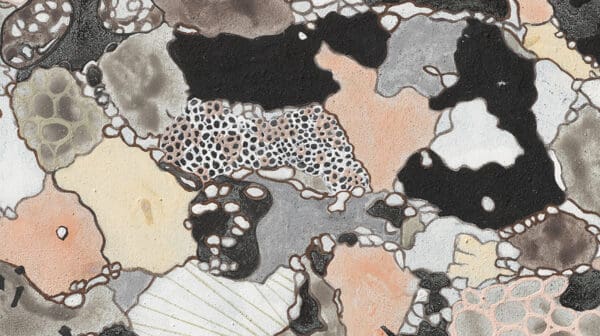

Shirozato to Shinju (White Sugar and Pearls) is the culmination of artist Elysha Rei’s creative research and practice exploring the interconnected histories of the Japanese diaspora in Australia, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries to the present day. Using the craft practice of 切り絵” (Kiri-e), hand-cut paper, Rei creates intricate works from single pieces of washi paper.

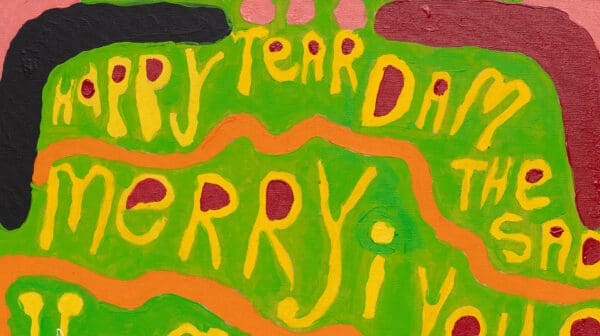

“I’m really interested in how my practice uses craft to lure people into this safe and beautiful space where they also encounter important and sometimes confronting historical stories,” Rei says. “There’s a tiny work with 114 punched holes in it, which just looks like a Japanese flag, but actually each of those holes represents the 114 people of Japanese ancestry who were able to remain in Australia after World War II, after thousands of people were interned or forcibly deported, some who had never been to Japan or spoken Japanese.”

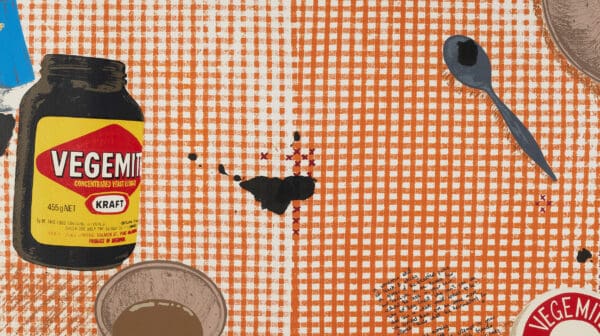

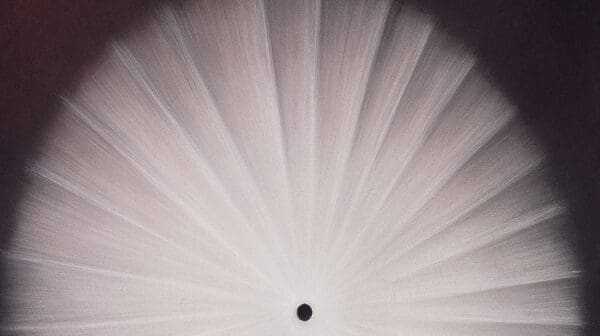

The late historian Tracey Banivanua-Mar referred to 19th century Northern Queensland as a colonial borderland, where race and whiteness were constructed and made invisible through the restriction of the freedoms, rights, and access to land of others. In forgetting the history of this construction, racial and national identities can seem immutable rather than the fragile fictions they are, built over the complex and interwoven nature of living communities through time. Townsville (Gurambilbarra) was the site of the first Japanese Consulate in 1896, during the final years of the Meiji Restoration, when thousands of Japanese people migrated for work to Australia. Elysha Rei describes how all her works in the exhibition are white as a reference to the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901, also known as the White Australia policy. “When that policy came into place in 1901, there were 3800 Japanese people living in Australia. They were pearl divers, sugar cane farmers, [and] families, and there was an erasure that came from this racialised legislative process, this bureaucratic violence of silencing these stories and histories.”

The works in this exhibition mark an expansion of Rei’s focus, building on her previous work exploring her personal Japanese lineage and ancestry to represent the stories of many Japanese communities in the Australian settler colony. “There’s one work that I’ve made that connects to the first recorded Japanese-Australian person, Sakuragawa Rikinosuke, who was an acrobat. I took his name, which means ‘cherry blossom river’, and created a papercut branch of a blooming cherry blossom tree pinned onto the wall with string like a tightrope.” Rei sent a preview of the work to a fourth generation Japanese-Australian ancestor of Rikinosuke, who was thrilled.

Rei describes the eye-opening experience of looking at newly digitised photographs and records accessed through a Postgraduate Fellowship with the National Archives of Australia. “I found out a lot of parts of Australia’s history that even I wasn’t aware of. I almost felt ashamed that I didn’t know enough about my own community’s history. There’s a sense of responsibility that I should really know about these histories, but also other people should know about these as well.”

This sense of responsibility and historical connection has affected the materiality of Rei’s work and process. “All these works are hand-cut in washi paper, which is a first time for me, that an entire body of work was made out of this substrate. This is a decision I came to when I did the Past Wrongs, Future Choices residency on Vancouver Island, Canada. The materiality is just as important as the content, as it is a substrate that has been sourced from Japan. There is one work made from sugarcane pulp in reference to Japanese labourers in the sugar cane farms as well.” Rei also describes how her creative process transformed during the creation of these works. “Usually I use a digital interface to plan works prior to cutting, but once I started to cut into some of the pre-planned works, something didn’t feel quite right about my original design, so I ended up abandoning that plan and started improvising in order to honour each story.”

As the inaugural chair of Nikkei Australia—an organisation preserving and promoting the legacy of the Japanese diaspora in Australia—Rei explores these stories not only as an individual artist, but as a community facilitator and representative, and as a supporter of historians. Her hope is that Shirozato to Shinju (White Sugar and Pearls) connects with people of all backgrounds. “I think it’s important to use contemporary art as a tool and a mechanism to engage with these histories, as a way to feel them, not just intellectualise them—that’s what’s really driving me.”

Shirozato to Shinju (White Sugar and Pearls)

Elysha Rei

Umbrella Studio Contemporary Arts

Townsville QLD

Until 27 July