Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Ella Barclay is a kind of techno-alchemist. She is known for her immersive installations in which computer wires, water, mist and diodes are transformed into pulsing organisms.

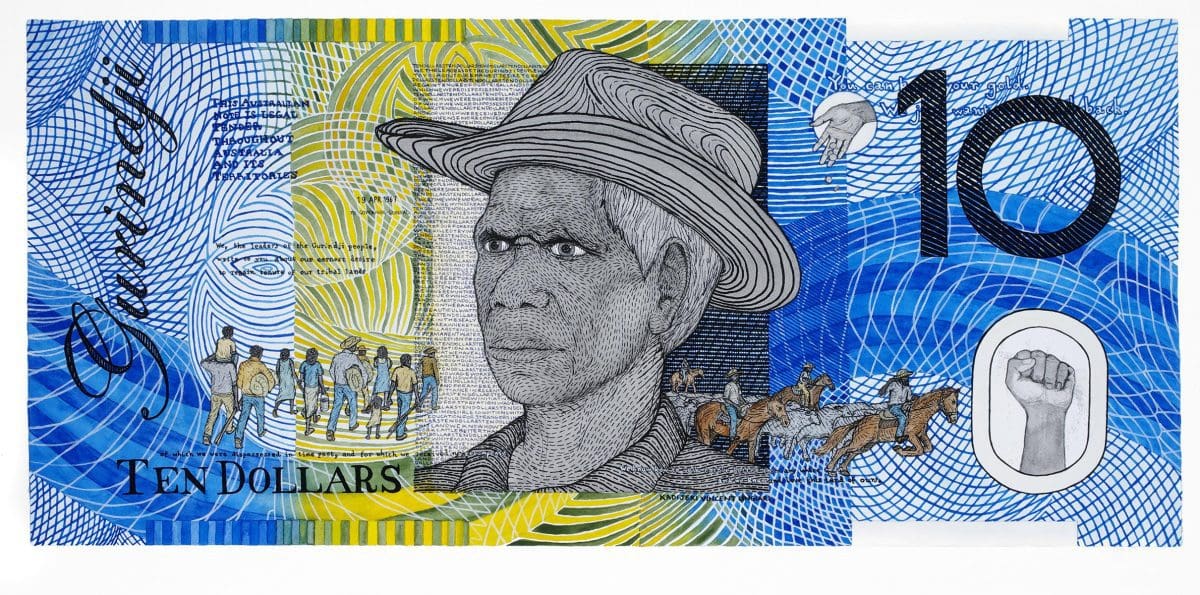

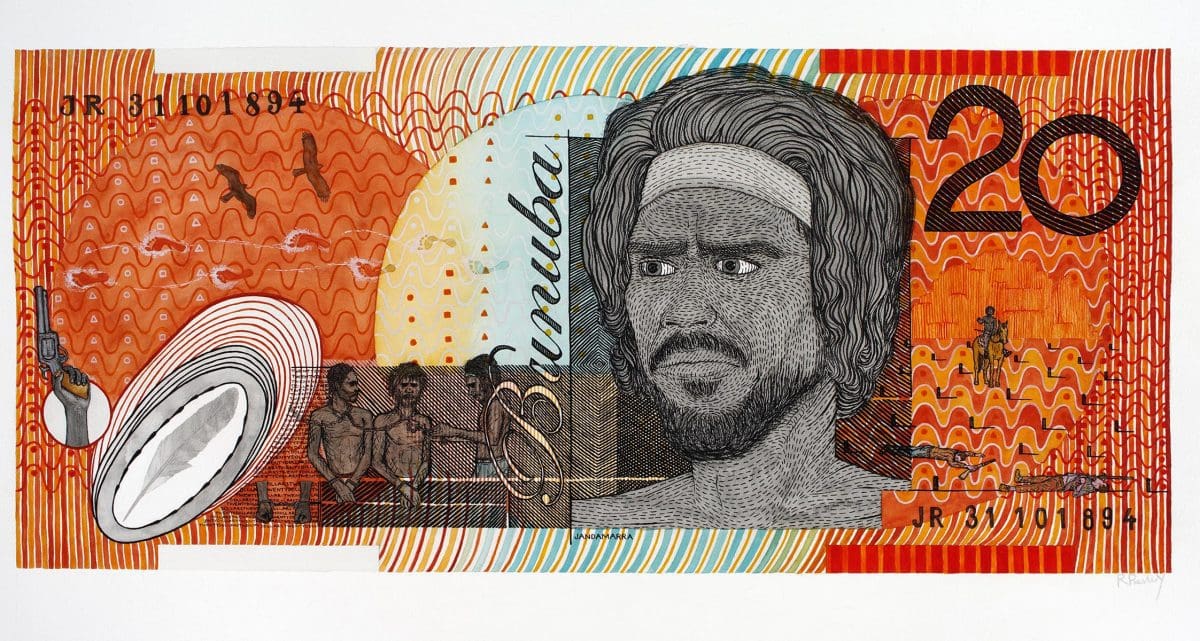

The show features: Hany Armanious, Simon Denny, Beau Emmett, Eva and Franco Mattes, Soda_Jerk, Jess Johnson, Alexis Mailles and Yujun Ye, Ryan Presley, Zoe M. Robertson, Suzanne Treister, and Pope Alice, an international line-up of artists and disruptors who challenge mainstream narratives of progress and technology. Rebecca Gallo talked to Barclay about conspiracy theories, post-truth in the post-internet era, and what it means to be an artist-curator.

Rebecca Gallo: You’re best known for your artistic practice. According to the internet, New World Order is your first outing as a curator or co-curator. What led you to branch out?

Ella Barclay: The last time I curated an exhibition was 10 years ago in Melbourne, and I’d sworn off it after half my artists disappeared on a bender during install week. This process has really been nothing like that. I’ve always been fascinated by other artists, and it has been such a privilege to put this show together. Casula Powerhouse has been really supportive, and my blue sky wish-list of artists engaging with this topic was nearly entirely answered.

RG: On the Casula Powerhouse website, New World Order is described as “an opportunity to think about how we make sense of the world in a post-internet era.” Arguably art is always a way of making sense of the world. What is it that drew you to these artists in terms of how they interpret the world?

EB: Conspiracy theories are central to this show, and have been an interest of mine for years. We’ve never had more access to information, but there has never been less truth. The show also looks at internet mysticism, and how knowledge structures are shifting. In a pre-internet model, knowledge came through the education system and political, legal and religious hierarchies. In the era of the internet that has all shifted, and people can seek out the information they choose. All the artists Toni and I have picked deal with these phenomena in one way or another.

RG: Could you talk me through a couple of the works and how they address those ideas?

EB: Sure! I’m really excited to be working with Eva and Franco Mattes. They were internet artists in the 1990s under a pseudonym [0100101110101101.org] and have developed an incredibly interesting critical practice over the decades. For the work in this show, they contacted content moderators for the big social media sites. These moderators, often based in India and the Philippines, look over and flag inappropriate content.

It is a globalised system in which the morals and ethics of workers in post-colonial, developing nations are making judgement calls on what we see in our feeds; they’re cleaning them. Which means that they’re exposed to the trauma of all the horrific shit that is cleaned away. The interviews, presented through digitally generated talking heads, reveal an underlying system that we’re not even aware of, but that is governing how we access information.

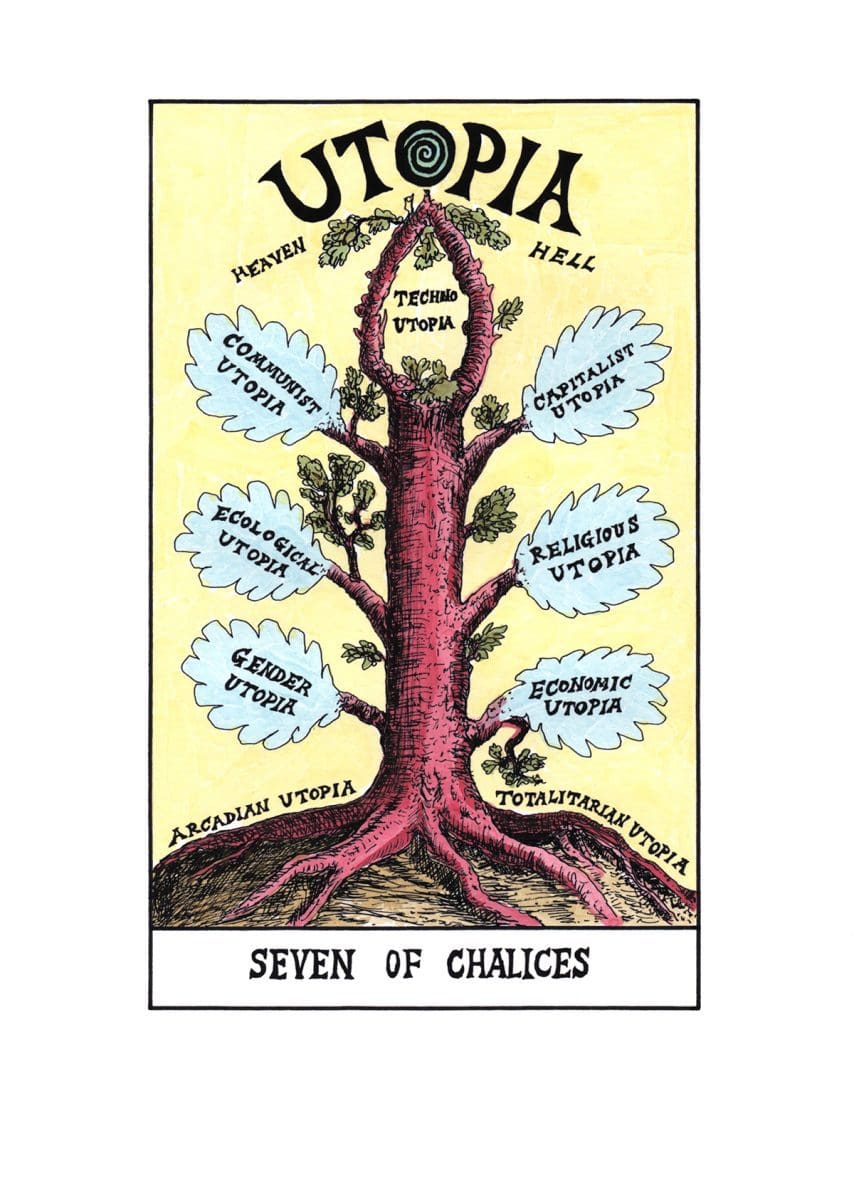

A lot of these net artists were real fringe dwellers in the 1990s, and I think the art world has finally caught up to them, not the other way around. That’s definitely true of Suzanne Treister, a British artist who is kind of a genius. We’re showing two works of hers, one is a series of banners, and the other is a set of tarot cards. Each of the 78 cards is represented by a drawing that speaks to relationships between computer programmers and psychedelics, philosophers or the military-industrial complex. We’re told a lot less about these stories than the Silicon Valley tale of a few white dude businessmen who dreamed a big dream.

RG: Is there any literature in particular (sci-fi, theoretical or other) that has provided inspiration for this show?

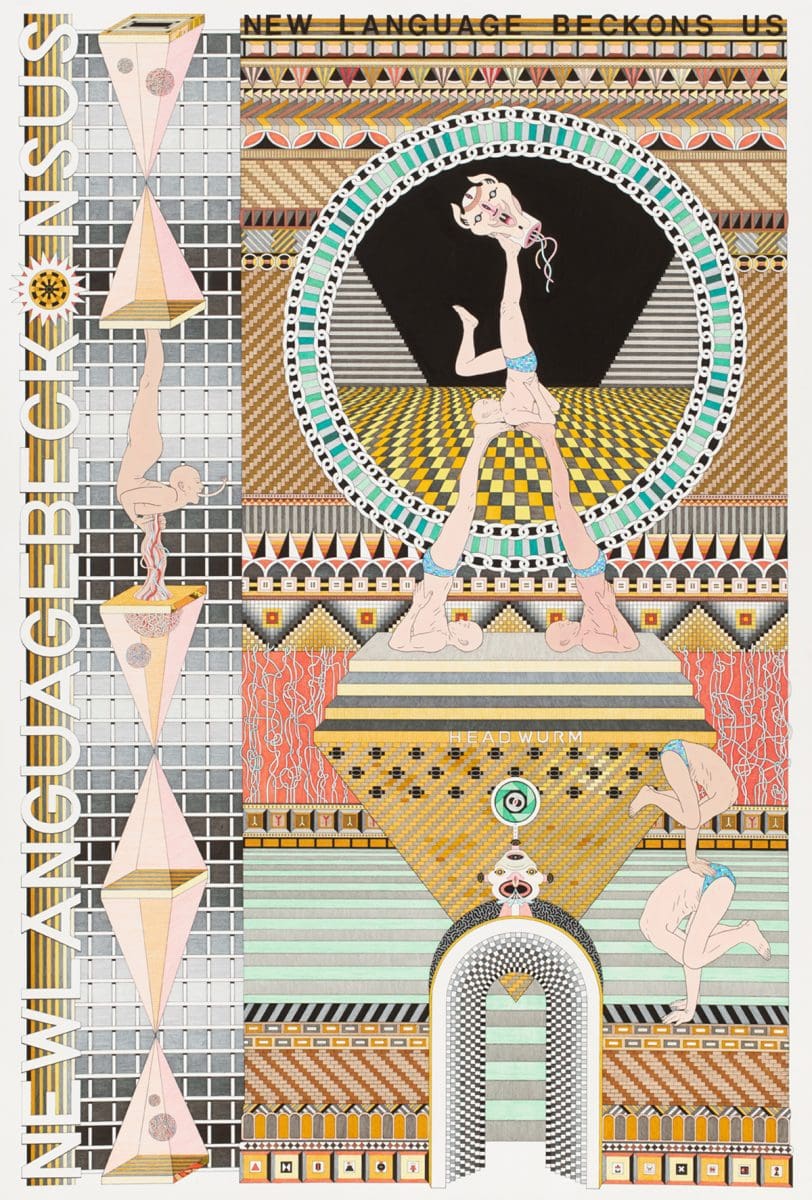

EB: It’s certainly the case for some of the artists. Taiwan-based artists Alexis Mailles and Yujun Ye are recreating elements of the cityscape from the beginning of Bladerunner. It’s a real check-in: have we arrived at this future? And Jess Johnson is heavily influenced by sci-fi, exploring very different writers, particularly from the 1970s.

It’s really interesting to look back at those techno-utopian hopes and dreams that went into building the structures that exist around us. I think this show is timely in lots of ways, with the US election results, and the fact that just yesterday, ‘post-truth’ was nominated as the Oxford English Dictionary word of the year.

RG: Funny you should mention the US elections. I was going to mention that when I did a Google search this week for New World Order, a lot of the links that came up were related to Trump.

EB: I’d love to say that I’m psychic, but I think we’ve known for about ten years that something was due to happen, and I guess now it’s starting. We’re experiencing a seismic shift at the moment, but how it will manifest we don’t know yet.

So much is going on: climate change, the destruction of the neoliberal dream, tech-icons are treated like royalty, the great data-acceleration. We’re not really even aware of how we’re using technology or what we want it for. We’re just kind of all turning into data feeds. Weird times.

RG: What do you think the artist’s role is at this time, as systems that have been built up over the last hundred years start to unravel?

EB: It’s a big question, and of course we all have different levels of institutional critique, and we have to ask whether having work that is passive in galleries and museums has real agency or not.

But at the same time, I think the level of criticality that artists offer the world is paramount. More and more in my daily life, I hear about creative people being brought in to consult with big corporations to offer insight into how to be critical and light on their feet. These are all skills that, since at least the 1960s, artists have been gearing up for.

Crossovers between art and science, research and creativity, are really powerful and in secular societies artists can be seen, as Bruce Nauman says, to reveal mystic truths. I think art is an amazing tool for people who are willing to see it.

RG: Do you think you will continue to develop a curatorial practice alongside making art?

EB: I think it’s important to do this show. In terms of a vocation, there are too many things that I want to explore within my own practice. But I really love what this opportunity has offered, and I’m definitely enjoying it. I think what a lot of curators love, is that even if you’re doing the most mundane things towards a show, you end up looking at amazing artwork. It’s energising work.

New World Order

Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre

9 December – 12 February