Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

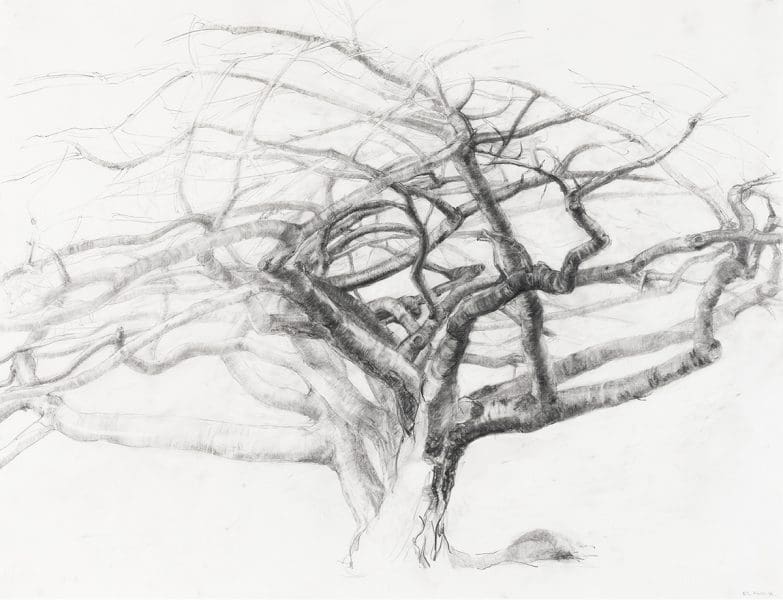

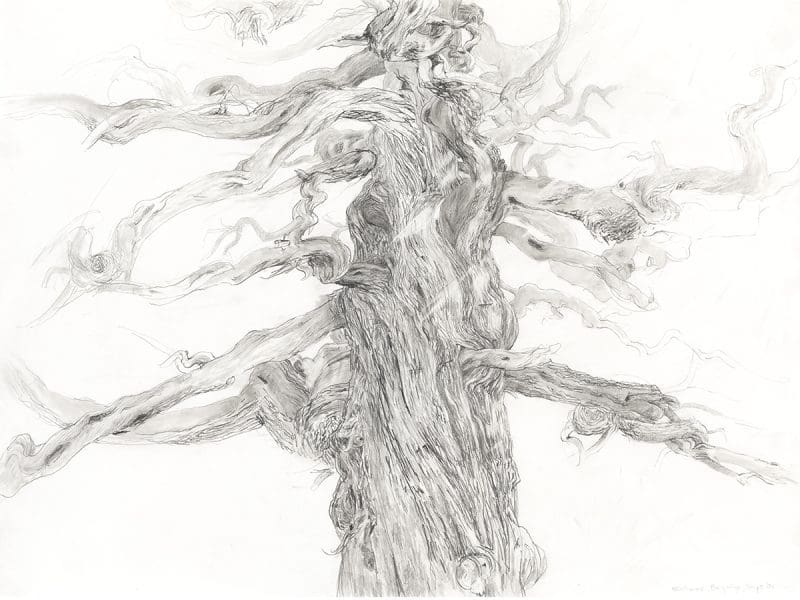

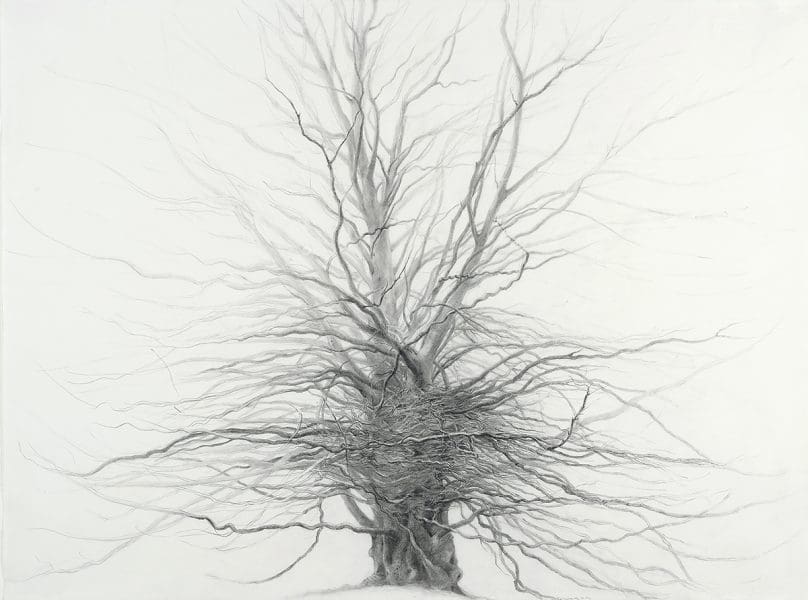

Melbourne-based curator and art historian Elizabeth Cross is less known for her own work as an artist, but this identification is shifting with the opening of her exhibition, Arborescent, at the Australian National University’s Drill Hall Gallery. Cross spends hours at a time committing pencil and graphite to paper en plein air, and is a regular fixture around Sydney’s Domain and Botanic Gardens capturing the Moreton Bay figs prodigiously planted throughout the harbour city. Steve Dow spoke with Cross about why she has kept her artistic talent largely hidden from public view, and the limitations of Western thinking about nature.

Steve Dow: Your Arborescent exhibition consists of 24 drawings of trees. Why are many of the trees depicted as denuded?

Elizabeth Cross: I’m responding very much to the trees as bodies; they have an allegorical alliance to us as human beings. We talk about being rooted to the ground or being grounded, and the twisting limbs of trees are very much like our own limbs and musculature. It’s an identification with the trees as a metaphor for our own existence. You could in some way see them as having an environmental statement, but that’s not their precise purpose. There’s a grander statement about the majesty and complexity of nature itself, and our closeness to that.

SD: In promoting your exhibition, the Drill Hall Gallery notes that the Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer and the baroque artist Claude Lorrain were also inspired by the lines of trees, likewise Cézanne, Van Gogh, Matisse and Mondrian. Which artists inspire you?

EC: Probably all of those people. I have been looking at drawings for a very long time. My ancient mother, months before she died, told me I had been drawing trees since I was a child.

I have looked quite closely at those wonderful early drawings by Lloyd Rees of Moreton Bay figs around Sydney. The density of mark-making in them, the concentration of tone, gives them an intense presence. It’s the sense of the rich quality of life. We imbue these trees with a spiritual meaning, but the sense of something intensely lived is for me their intrigue.

I certainly have looked at Dürer’s wonderful etchings, and that early series of Mondrian’s trees that morphed finally into abstraction; those grand apple trees he drew. Odilon Redon, the French symbolist artist, made some wonderful studies of trees. There’s a whole language of them.

When I used to sit in the parks in Paris and draw the bare trees in winter, people would often stop, and because art is much more woven into European lives, you would get conversations about other artists who worked in the manner I was working in.

SD: Did you have a pastoral upbringing?

EC: No! Not at all. Very suburban upbringing. I was born in Williamstown, Melbourne and we moved to the western suburbs. But my family cultivated a garden and loved trees. My father, who was an Englishman, mourned the absence of lots of oak trees, but he would take us to see the elm trees in autumn in the Fitzroy Gardens.

I spent a lot of time working and living in Europe, so I drew a lot of deciduous trees there. But I grew up with those in Melbourne, which, a bit like Canberra, has wonderful deciduous trees. In the Jardin des Plantes in Paris, which dates to the age of Enlightenment, they have a wonderful collection: great Cypresses from Lebanon, and wonderful Prunuses [the genus that includes cherries and peaches] that are probably a couple of hundred years old; an extraordinary tangle of branches that seem to have a weight of air on them as autumn descends. Very crusty barks on the lower end of the trunk, so you get this range of textures.

SD: Can you talk about the media and method you use to draw trees?

EC: I sit in front of trees for hours. I never work from photographs. I did work for a while in pastel and charcoal, but I now work almost exclusively in pencil and graphite. I use mostly fairly light pencils, I use an HB, and I’ve used harder pencils: B and F pencils. Some darker 6B pencils, which give a much richer black sheen, rather than silvery grays. And I use a tightly rolled soft paper [a stump] that acts like a pencil, but which you can use to spread the graphite on the paper. I use an eraser to take some of the graphite off, to bring the highlights back, or catch the effects of light. I sit with a large board on my lap with a large sheet of paper, on a folding stool. I work on smooth paper, a hot press paper because I love the way it allows the graphite to slide across.

SD: You are best known as an art historian and curator. Why have you kept your talent out of the public eye?

EC: I loved teaching art history when I was teaching in the 1980s through the early 90s. And it’s very demanding, so drawing was done in patches. I always felt uncomfortable making grand claims for myself as an artist since I wasn’t working day in and day out like fellow artists.

I think in museum culture there has been a slight sense of prejudice against people who are artists as well as curators – as though that might make them prejudiced about what they were looking at. Which is in a way a nonsense because we all have preferences for kinds of art. There has been that sense you need to be one thing or another. I showed work when I was very much younger.

SD: In January, the Federal Government rejected an application by an Indigenous group to stop sacred birthing trees being torn down to duplicate a highway in Western Victoria, but in April, the world convulsed when Notre Dame burned. Why do people seemingly care more about buildings than about trees?

EC: Yes, it’s a very interesting phenomenon. This is in a way a measure of Western societies, and the post-Enlightenment valuing of human endeavour rather than of nature itself. There was a much greater synergy between nature and human activity, even up to the time of the Renaissance. But increasingly it became about what mankind achieved under our own steam.

Buildings have become a measure of what mankind has achieved with civilisation, whereas trees are always something that has been there and live independently of us. It’s a very egocentric thing, I think, Western culture is in a way, ‘We made this, and that’s more important than what nature is doing.’ And we’re all finding out to our cost that this is profoundly erroneous and destructive of our capacity to go on living on the planet.

SD: So, you fear for the future of the planet given forest and habitat destruction?

EC: I do, without any doubt. Like many people, I subscribe to a lot of the great work being done by environmental groups. I think we are rapidly destroying our planet, and that’s quite tragic. If my modest tree drawings are a reminder to people about the fundamental existence of things beyond us, then that’s really good.

Arborescent

Elizabeth Cross

ANU Drill Hall Gallery

20 April – 9 June