Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Mathematical Expressionist is a survey of work by painter Edwin Tanner (1920-1980). Accompanying 60 works from Tanner’s 30-year oeuvre is The Arbour and the Orrery, by artist and composer James Hullick whose mechanised sound installations engage Tanner’s works in dialogue. Anna Dunnill spoke to exhibition curator Anthony Fitzpatrick about Tanner’s ongoing legacy, the links between music and mechanics, and the impact of technology on human life.

Anna Dunnill: Edwin Tanner’s painting was influenced by his many diverse interests. What was his background?

Anthony Fitzpatrick: Tanner left school at about 14-years-old, during the Depression. He was a high achiever and determined to excel, so he studied by correspondence and achieved his professional engineering qualifications. He moved to Tasmania in 1950 with his young family and became an engineer in charge of a hydroelectric commission there.

That was also when he began painting. He’d never studied art, but at the age of 30 he enrolled in art lessons at the local technical college while working full time, and then took on an arts degree where he majored in philosophy and literature. He also struck up a friendship with Gwen Harwood, one of Australia’s leading poets, and had a decades-long correspondence with her.

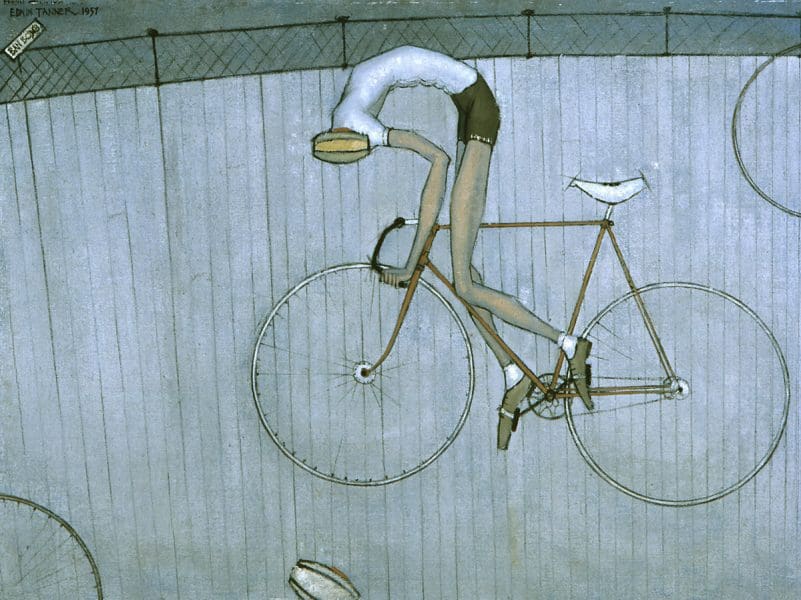

Somehow all these different influences – his work as an engineer, cycling, his experiences as a pilot, his interest in music and literature – made their way into this very complex rich pool of imagery and experiences from which he could draw out his idiosyncratic compositions. It’s little wonder that people couldn’t pigeonhole him or position him in a particular school.

AD: Can you tell me about James Hullick’s new work The Arbour and the Orrery – and what does ‘orrery’ mean?

AF: Traditionally, an orrery is a moving 3D model of the solar system: a central disk with different arms and armatures holding up the planets, which rotate around the sun on their ellipses. James has used this idea in his sculptural sound piece The Orrery of Human Desires which has three arms suspended from a rotating disk. Instead of a planet at the end of each arm there’s a speaker that will emit the sound of an original musical composition. James has written two scores, each in response to one of Tanner’s paintings: Operatic Aria, 1960, and Odd Man Out,1964, and the orrery will play those as it moves in a circular fashion. It’ll be interesting to see how the sound is affected by the speakers rotating through space.

He’s called it The Arbour of Doors, and is constructing a kind of speaker-cave made out of fitted-together door frames. Within that are recycled audio-visual components that will play a soundtrack he’s recorded, and some of Tanner’s poetry recited by volunteers direct to camera. These two installations continue James’s interest in the spatial qualities of music. Both the Arbour and the Orrery could be conceived of as new instruments in a sense.

AD: What are the challenges of presenting sound works in the gallery space?

AF: It’s always a bit of a negotiation. Every museum knows when you put on sound works it’s something that, unlike a static work on a wall, takes on a life of its own and infiltrates space. But we do want the two shows to interact. In a way, what James is doing is letting us know what it might sound like if some of Tanner’s paintings did emit sound.

AD: In Tanner’s earlier work there’s a technical drawing quality and engagement with mechanics, and then an increasing anthropomorphising of mechanisms. Would you say that’s a connection between the two artists?

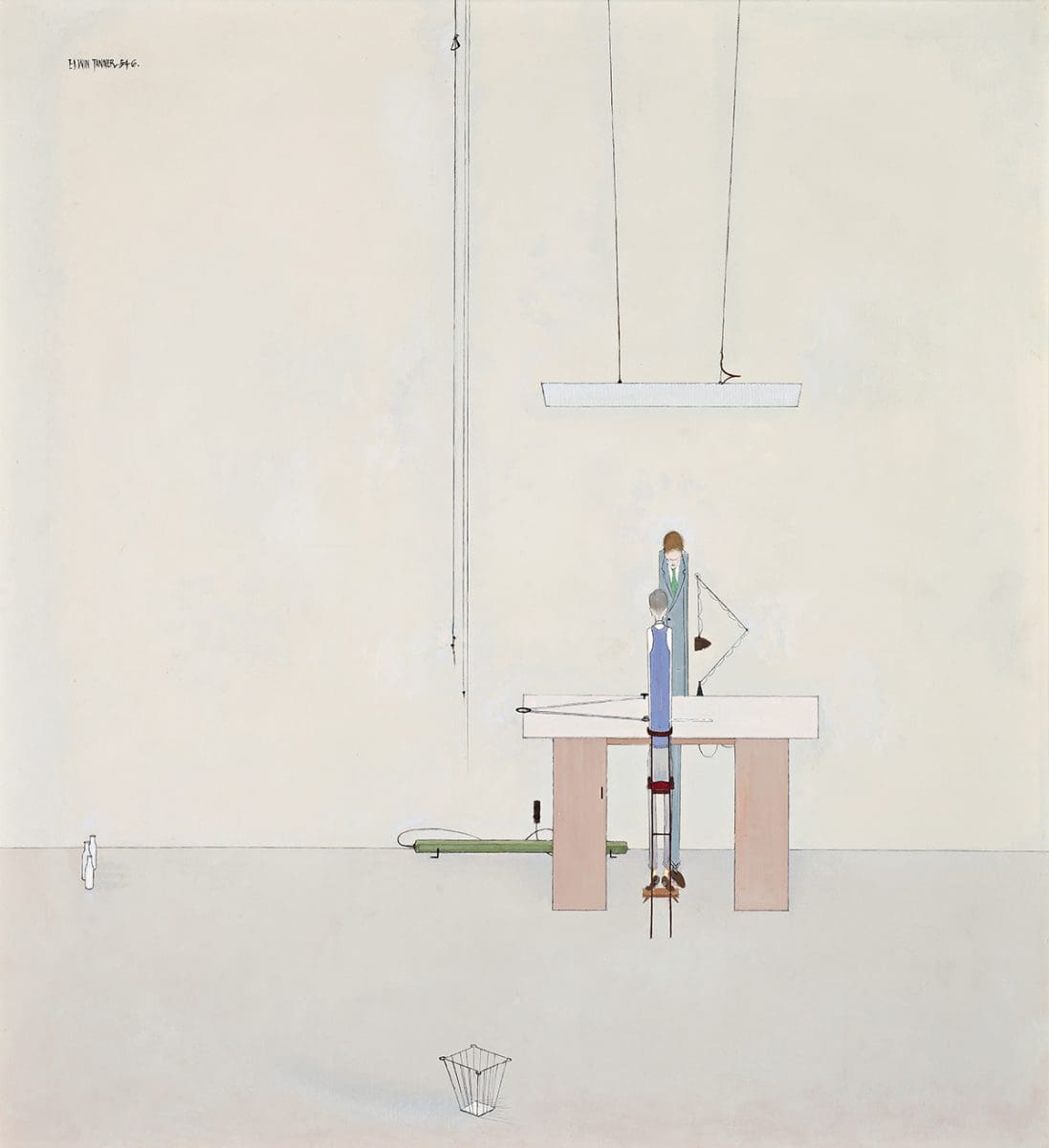

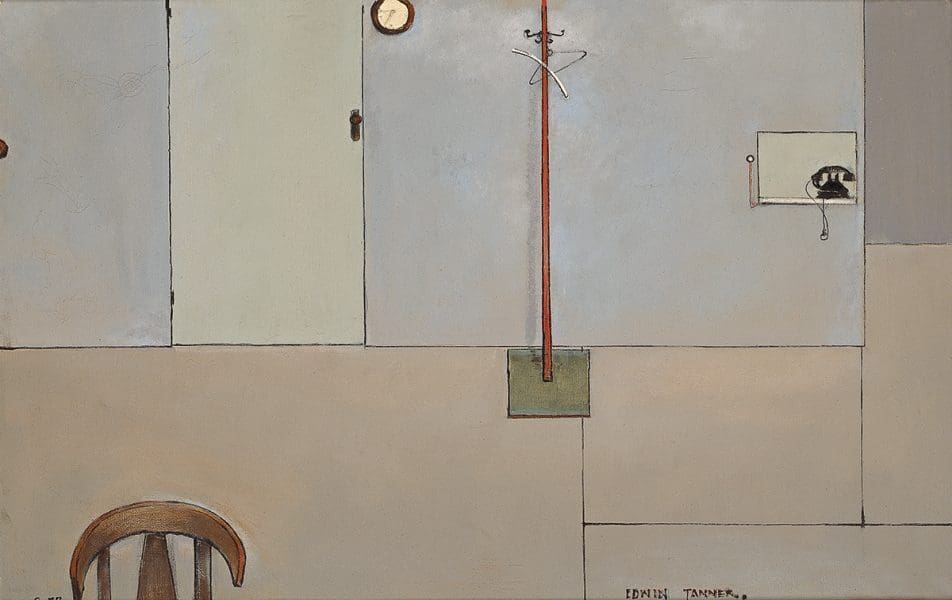

AF: Yes, these were the paintings that James responded to. They look like they’ve come straight off the drafting board, some of those early works; the figures are quite elongated. But then gradually the human figures morph more into machine-like entities and the machines take on a life of their own.

Tanner was also interested, as a lot of abstract painters have been, in how ‘composition’ is the same word we use for a sound piece and a painting, and how elements of painting can evoke the qualities of sound: the modulation of colour or even the placement of elements can be read like a score. That translation between painting and music is something Tanner explored; the paint having a rhythmic quality, or pulsating in a way.

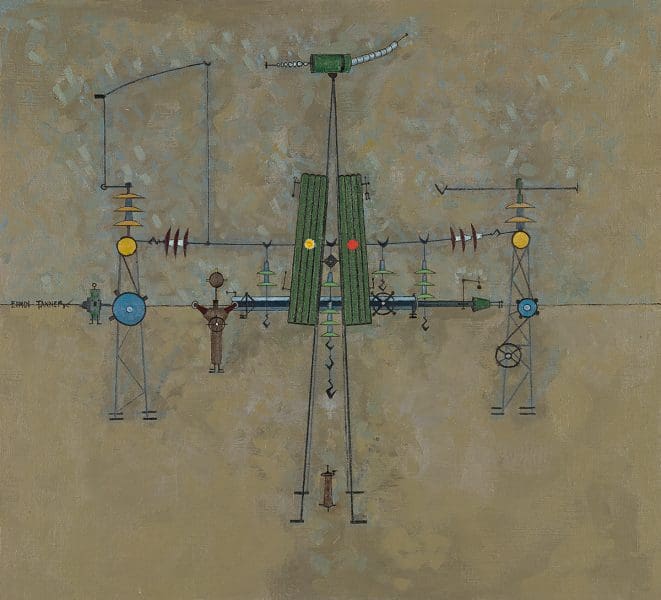

In one work, Madrigals, 1960, Tanner has rearranged the components of an electrical switching station into this ensemble of parts that look like they’re conducting, or some kind of strange music is being generated out of industry. In another, Lightning Conductors, 1961, there’s a row of quasi-mechanoid humanistic things with faces, made out of bolts and rods and parts, floating in a very ethereal cloud like background. They’re all cobbled together out of different components, in the way that James constructs his mechanical systems. Of course the title is a play on words: a lightning conductor which burns electricity, and also a conductor of music.

AD: This is the first survey exhibition of Tanner’s work since 1990. How do you think his work reads in a contemporary space?

AF: For me, these works look at a fluid interrelationship between humans and technology. For someone who was so intimately involved in the technological infrastructure and environment that is now the world we inhabit, there’s a foreshadowing of the increasing digitisation and mediation through technology that underpins so much of our daily lives.

In the paintings from the 1950s and 1960s, computers and cybernetics were burgeoning, and Tanner was starting to see the way automation was replacing the human role in manufacturing and industry.

AD: Do you think the darker sides of technology is something that Hullick’s work explores as well?

AF: Yes, a lot of his work has a social comment to it. Like Tanner, he’s concerned with the human condition and how our interface with technology can impact on our relationships. How we think about our place in the world, how we interact, how we communicate. Those things are definitely present in both artists’ work.

Edwin Tanner: Mathematical Expressionist

James Hullick: The Arbour and the Orrery

TarraWarra Museum of Art

12 May – 15 July