Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

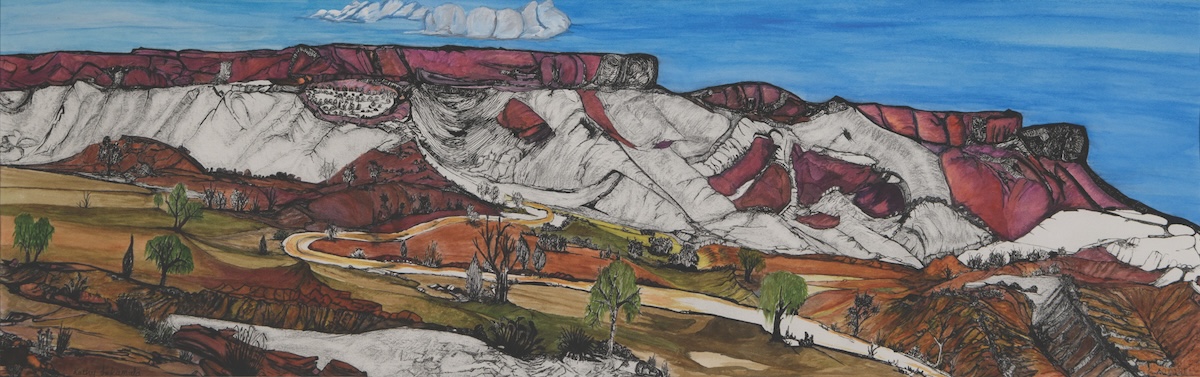

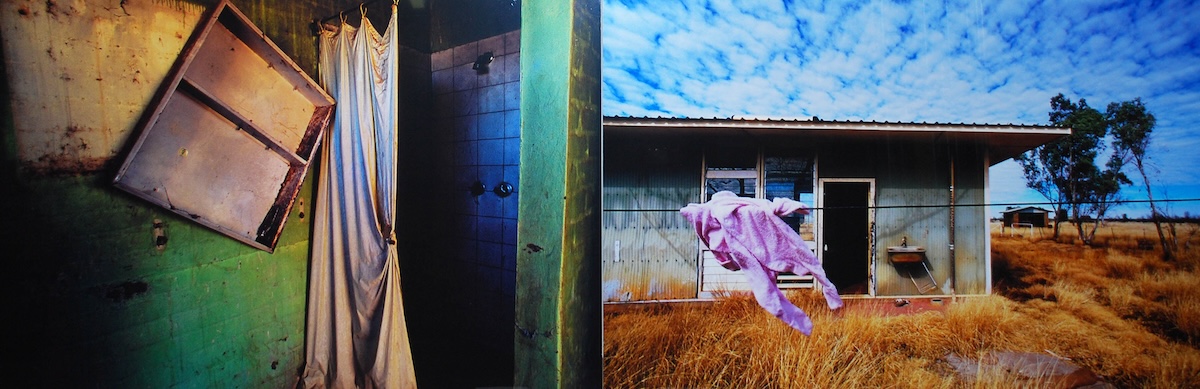

In 2013, when New Zealand-born artist Jennifer Taylor painted her mountainous oil triptych Lost landscapes in situ at Ross River, east of Mparntwe/Alice Springs, she had been immersed in that particular part of Arrernte people’s country for three years.

Being non-Indigenous, Taylor, who has lived in Alice Springs since 1994, benefited from conversations with Aboriginal Elders who had been born and grown up there. “I was grappling with that sense of being in a place, as someone who doesn’t know the place,” she says, “and trying to come to see it properly through painting.”

On the day Taylor painted the work en plein air, industrial earth movers were stirring up dust, the resulting filtered light incorporated by the artist on her canvas. Beneath that surface, however, Taylor was trying to grasp histories invisible to visitors: strong cultural ties and land rights Arrernte people held over the area.

Lost landscapes will feature in a large exhibition, GROUND SWELL, celebrating Araluen Arts Centre’s 40th anniversary in Alice Springs, among some 200 works comprised equally of Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists. In painting her work, Taylor says she felt a “sense of loss and sadness” that colonisation had changed traditional lives “so radically”.

The gallery and collecting institute, funded by the Northern Territory Government, champions Central Australian artists responding to Country, place and the “heartbeat of the region”, says curator Stephen Williamson. This focus remains unchanged since the centre opened in 1984 on land once occupied by the old Alice Springs airport.

Today Araluen boasts some 1,100 works in its collection, focused on collecting art in dialogue with the Central Australian region. The centre is not only a keeping place for stories and significant works, but presents performance and film in its 500-seat proscenium arch theatre. Local artists are celebrated with exhibitions and creative residencies within the wider cultural precinct.

Across three of its four galleries, artworks in GROUND SWELL will be presented grouped in “currents”—five themes respectively named catalyst, immersion, collision, divergence and surprise—which Williamson says is a way of “breaking down constraints to focus on the whole collection”, rather than presenting Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists in separate spaces.

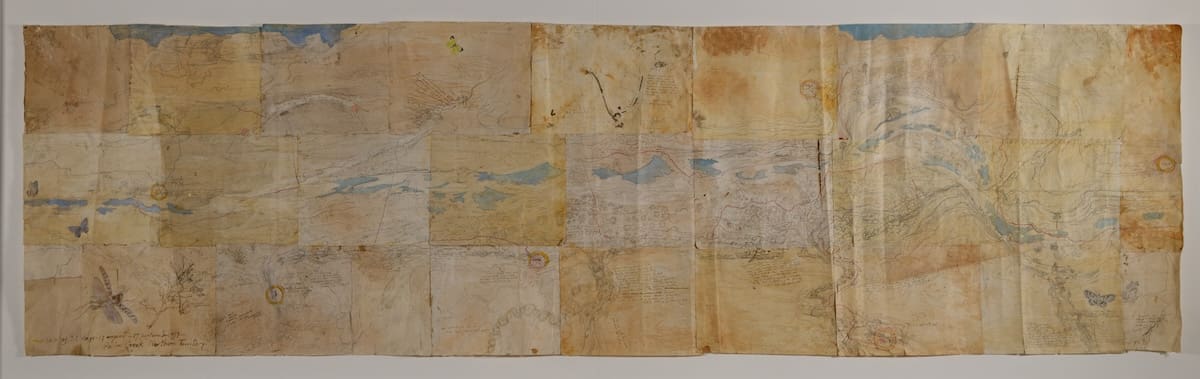

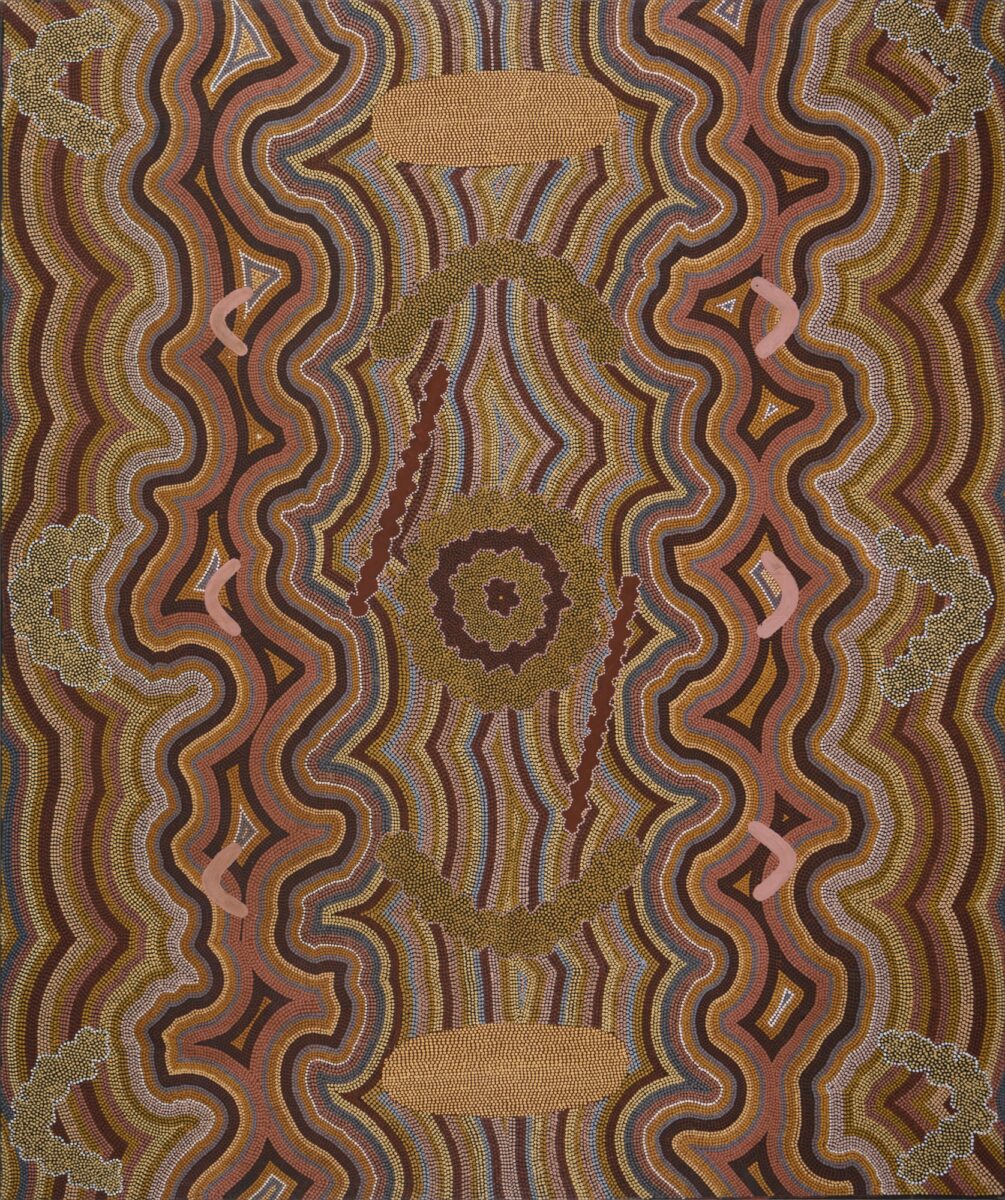

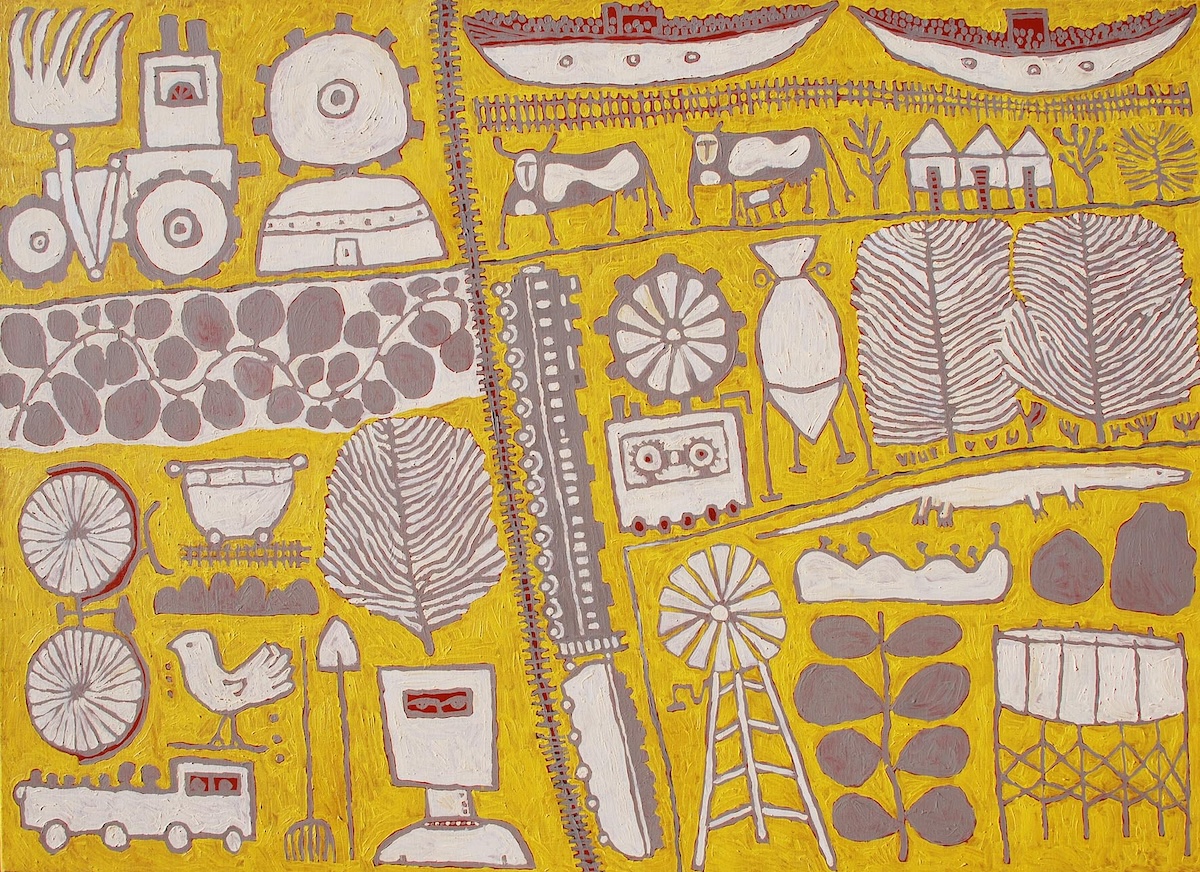

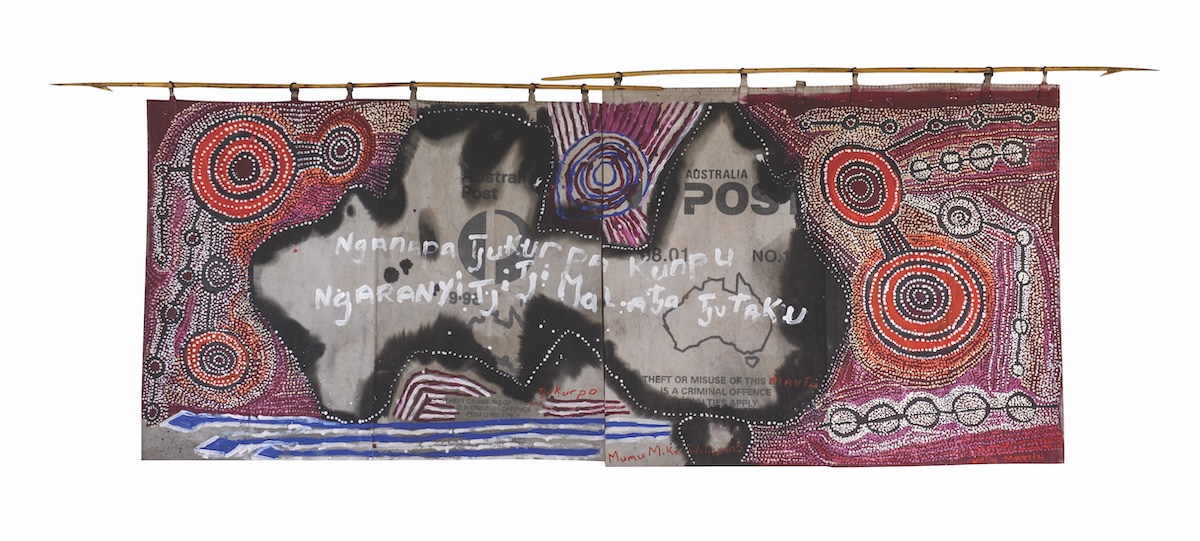

Through juxtaposition of artworks, audiences can contrast and speculate on influences. For the curator, the exhibition’s starting point was two very different works: Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri’s 1983 acrylic on linen work, Mulga seed Tjukurpa, “drawing on cultural knowledge handed down for millennia”. This is contrasted with UK-born John Wolseley’s 1980 mixed-media Map of 32 Days, articulating Wolseley’s interaction with the landscape over a month spent at Palm Creek in 1978.

Both Tjapaltjarri and Wolseley’s works won the Alice Springs Art Foundation’s The Alice Prize, open to artists across Australia, established in 1970 as a way to bring contemporary art from around the country to more isolated regions, and which today is run as a biennial event.

Part of Araluen’s ongoing significance is its collection of winning entries from this prize as well as those from the Central Australian Art Society’s Caltex Art Award. That award was established in 1968 and, a decade later, became the Northern Territory Art Award. Today, it is known as the Advocate Art Award, and is open to all artists from Central Australia.

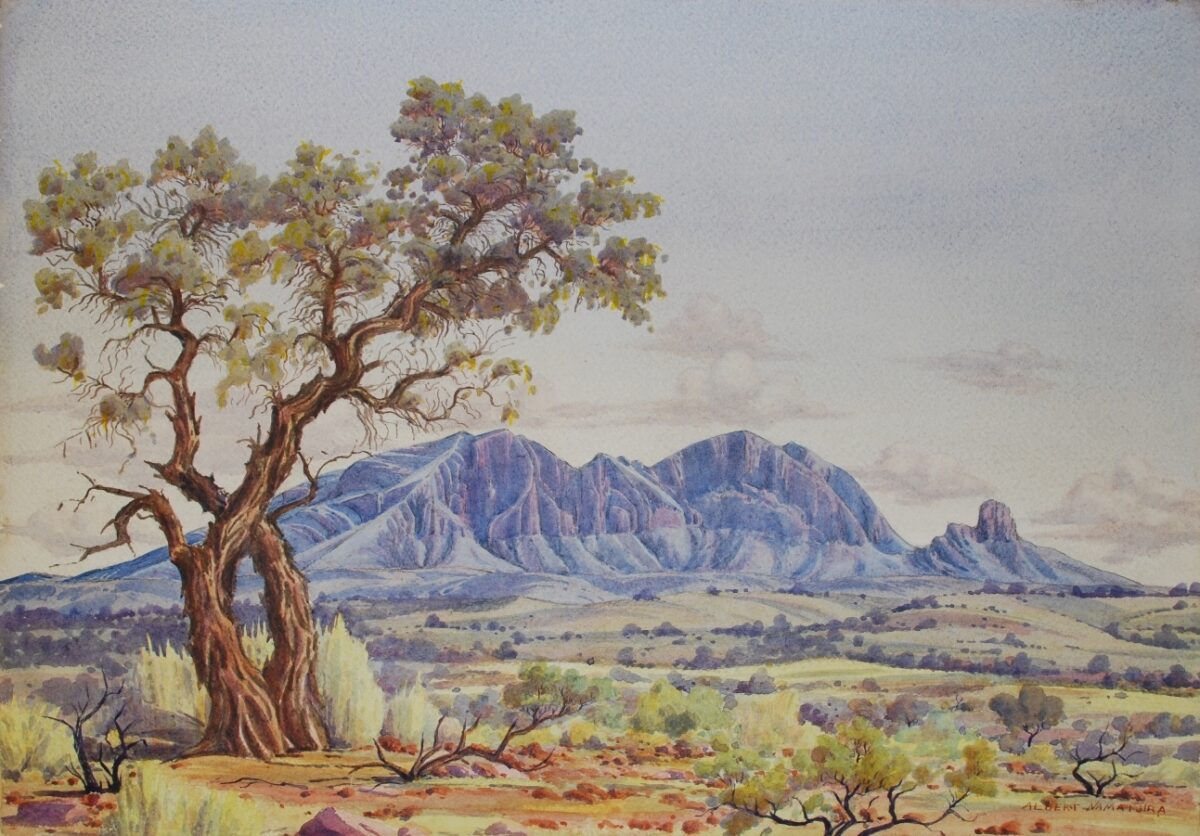

Yet Araluen’s most requested artist has always been one of Australia’s most celebrated artists, Arrernte watercolourist Albert Namatjira—and 18 of the famous Hermannsburg painter’s canvases will feature in GROUND SWELL, spread across the five thematic currents.

Williamson notes Araluen’s first show in 1984 was the first ever retrospective of Namatjira’s work, 25 years after the artist’s death in 1959. The 56 works that were on display finally influenced institutions to start collecting Namatjira’s output, already long adored by the public. “Some institutions had been quite critical and thought it was too European-influenced,” says Williamson. “This exhibition really changed the way his work was viewed by critics and the like; there was a new appreciation for what he had done.”

In GROUND SWELL, Jennifer Taylor’s Lost landscapes will be grouped under the theme immersion, into which Namatjira’s circa 1944 work Mount Sonder with Corkwood Tree has been placed. Taylor also painted the Hermannsburg mission as part of an Araluen creatives-in-residence program, a year-long residency allowing her to forge connections with Indigenous communities. She feels deeply indebted to Araluen given its commitment to art both from and about Central Australia, and was “absolutely” inspired by Namatjira’s “mastery”.

In 2018, Taylor titled her Araluen exhibition Dreams of Home, suggesting everyone living in Central Australia might collectively dream of home, while ultimately acknowledging Indigenous belonging to Country. “What are the differences and the overlaps in the ways we think about home?” she asks. “The onus is on us to understand where we are, and do our best through relatedness and respect.”

GROUND SWELL: Araluen at 40

Araluen Arts Centre

On now—11 August

This article was originally published in the July/August 2024 print edition of Art Guide Australia.