Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

A cacophony of sound cascades towards the ground floor of the Ian Potter Museum of Art. Nothing is singularly discernible, but the impact is strong. Eavesdropping, curated by Joel Stern of Liquid Architecture and Dr James Parker of the Melbourne Law School, tackles some big issues: technology, surveillance, privacy, detention, migration, and more.

Entering the exhibition a bodiless voice says, “Hey Siri, are you spying on me?” On the floor lies Sean Dockray’s installation, Always learning, 2018, in which an Amazon Echo, a Google Home Assistant and an Apple HomePod appear to be communicating with each other. It’s not clear which device asked the question.

As the strange ‘conversation’ continues, there are moments of humour – “Hey Siri, how do you make a bong?” But then, setting the tone for the rest of the visit, a machine eerily asks, “So if they don’t trust us, why do they have us?”

The exchange of information – illicitly or otherwise – is central to this exhibition. But a number of works focus on interpretation of information. For example, in Cosmic Static, 2018, by Fayen d’Evie and Jen Bervin with Bryan Phillips and Andrew Slater, we hear non-human transmissions recorded around the world. They are played simultaneously through eight speakers in the room, relaying complexities that can be found in non-verbal communication. These sounds may not mean anything to us, but if we are not the intended audience, it might mean something to someone, or something, out there. Who are we to dismiss anything as mere noise?

In Conflicted Phonemes, 2012, British-Lebanese artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan shows how language and voice are unreliable tools to use in policing migration. Focusing on Somali asylum seekers, Abu Hamdan presents what he calls ‘forensic interview’ results in which a select group of interpreters and translators determine asylum status based on the pronunciation of just a few words. A vinyl wall display and printed collateral map out the complexities of geography and language, showing how this practice denies the fluidity of language.

In another work involving asylum and migration, how are you today, 2018, by the Manus Recording Project Collective (facilitated by Melburnians Andre Dao, Michael Green and Jon Tjhia), we listen in on a few men stranded on Manus Island (Samad Abdul, Farhad Bandesh, Behrouz Boochani, Hass Hassaballa, Shamindan Kanapathi and Abdul Aziz Muhamat) as they go about their lives. The recordings are made daily and transmitted to Melbourne as quickly as possible. On the day of this visit, a recording of Aziz watching the World Cup final with the guys last week was played. Since then other recordings have been made: Samad listening to music, Farhad playing music and making tea, Behrouz walking in the jungle. So far away, yet so similar.

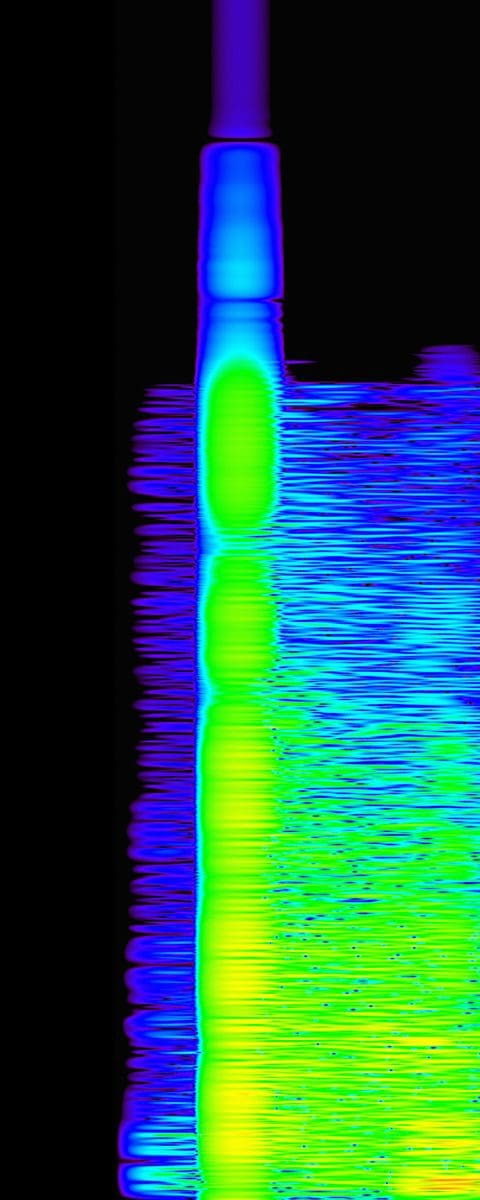

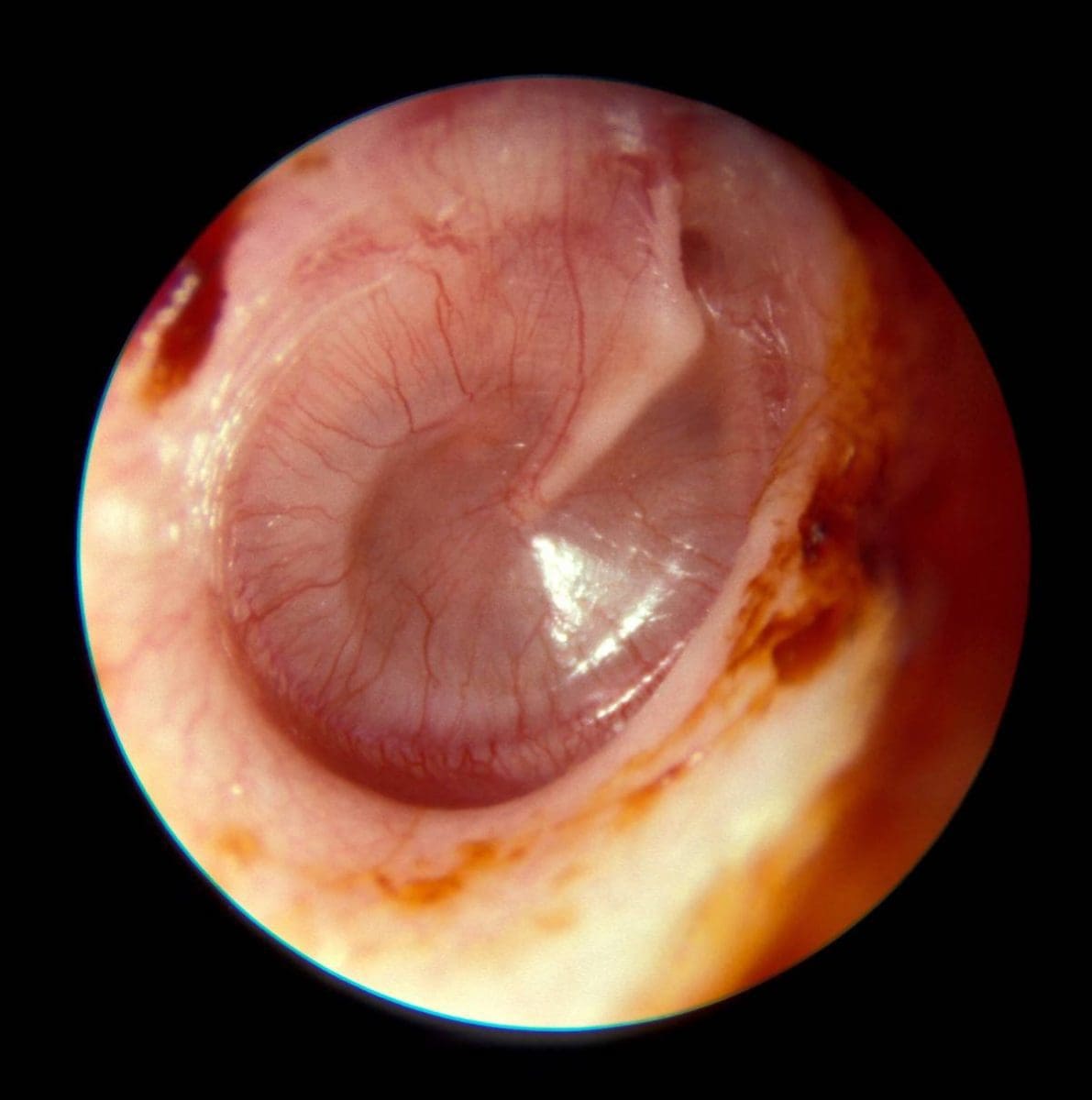

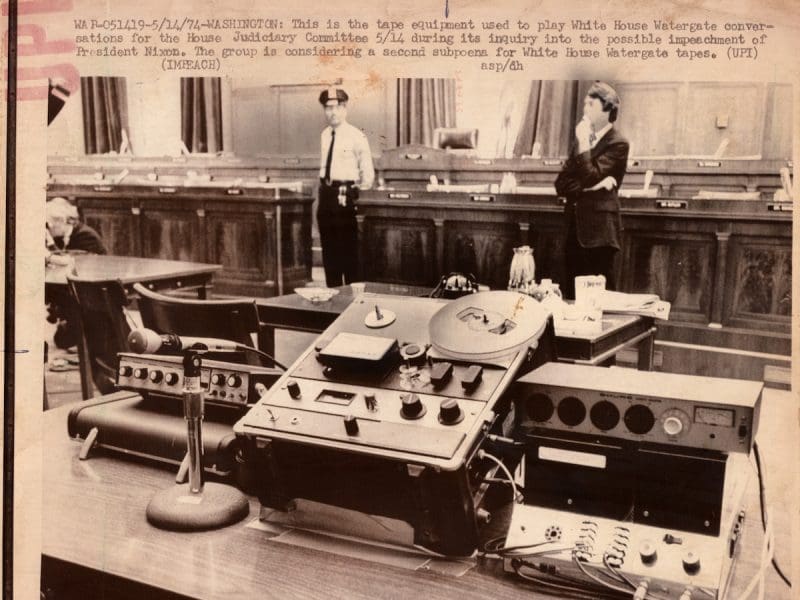

The absence of sound is as significant as its presence in Susan Schuppli’s The Missing 18 ½ minutes, 2018, and in another work by Abu Hamdan, the audio installation Saydnaya (the missing 19db), 2017.

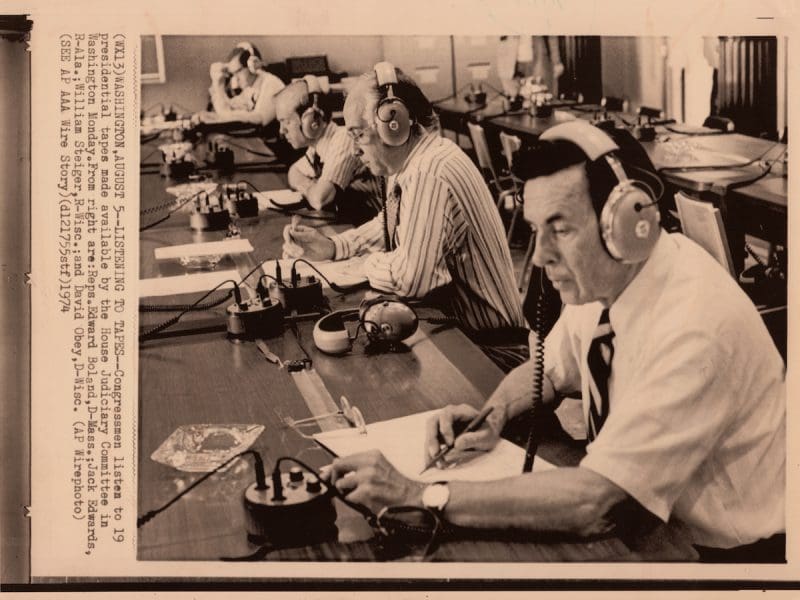

Schuppli’s work is an investigation of the Watergate scandal, and the title of her installation refers to the infamous 18.5-minute gap in Watergate Tape 342. In 1974 Nixon’s secretary, Rose Mary Woods, testified that she accidentally erased the recording while reaching over to answer a telephone call. Included in the exhibition are photographic reproductions of Woods re-enacting the incident, press imagery of the trial, and, crucially, the full 18.5 minutes of the missing audio in Tape 342.

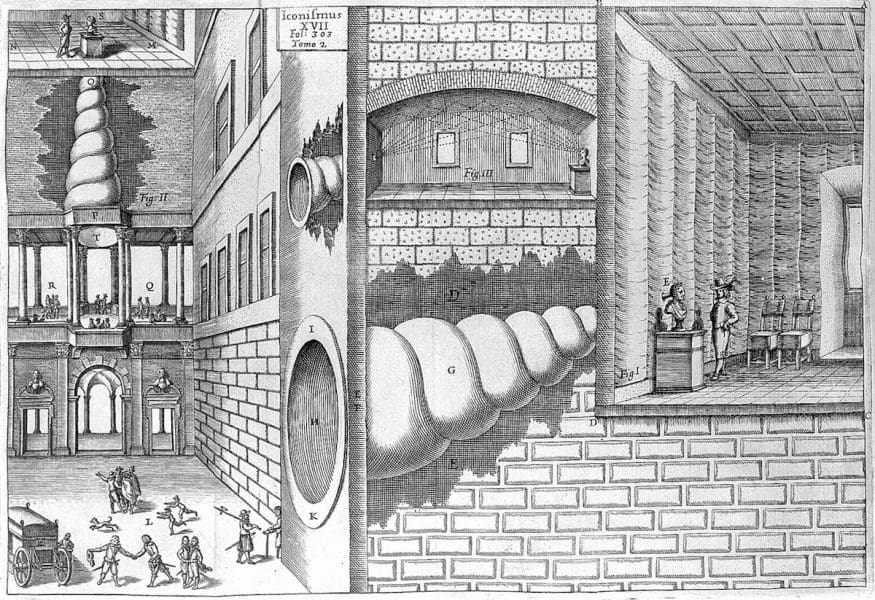

Since 2011, 15,000 people have been executed at the Saydnaya Military Prison in Damascus. Through this work, we hear tales of prisoners learning to navigate silence to survive their sentences. Abu Hamdan demonstrates decibel measurements of common sounds to demonstrate the depth of 19db. At 150 db, your eardrums could rupture. A whisper roughly sits at 20db. At 10db, breathing is barely audible. Life in Saydnaya is surviving between a whisper and a breath.

Exiting Saydnaya’s silence is disorienting, not least because Susan Schuppli’s Listening to Answering Machines, 2018, assaults you as you emerge from the quiet. A soundtrack of personal phone messages accompanies an installation of old answering machines and tapes. These objects are obsolete, but the recordings live on. It’s obviously a meditation on technology, privacy and legacy, and it is here that the exhibition comes full circle. Where will Alexa, Siri, and other devices of today end up? Who is listening in to the minutiae of our lives without our permission? Who is judging, or policing, our lives?

Eavesdropping

The Ian Potter Museum of Art

24 July – 28 October