Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

Doug Aitken turns his viewers into participants. In his first Australian survey, New Era, the American multidisciplinary artist wants imaginations and spirits to take flight: audiences could be “anywhere and everywhere,” he says. “You can really fall into the works.”

Aitken recently created Green Lens, a mirrored pavilion on the Venetian island of Certosa for fashion brand Yves Saint Laurent. Such “landscape interventions”, for which he is famed, draw attention to the limitations of conventional galleries. He is adept at transforming such spaces, however, with light, reflection and sound.

Now he is back in the gallery: at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, Sonic Fountain II, 2013/15, is a large-scale sound installation built into a rocky, earthen terrain. NEW ERA, 2018, on the other hand, is an immersive video installation inspired by the history of mobile phone technology.

Inspiration for this latter piece comes from American engineer and mobile phone pioneer Martin Cooper, now 92, who is a pioneer in the wireless communications industry. This is an interesting throwback for Aitken, given the artist has recently expressed interest in “post-screen work” and a “return to the real”, as the world gradually emerges from a year-and-a-half dominated by screen-based information during the pandemic.

What sort of inferences, perhaps even unintended meanings, might an immersive and expansive exhibition such as New Era take on for an audience whose physical worlds have literally been made very small and confined by this virus? “Ideally, I would love to see this exhibition as something that can really be authored by the viewer, that can empower the viewer to navigate and explore and to be in a dialogue in a way that might be refreshing and different,” says Aitken.

Speaking via video conference from his Venice Beach, California home, Aitken, aged 53, exudes a youthful glow that prompted Smithsonian magazine to call him an “overgrown beach kid”. And his curiosity is persistent: “Culture has really helped us survive [the pandemic] and have a larger dialogue with people we’re intimate with, but also society.”

New Era consists of a “collage” and “kaleidoscope” of works spanning 25 years of Aitken’s practice. It is a “composition of different ideas and encounters” which are “very specific to the show in Sydney: how to make something that you physically walk inside the museum but experientially it seems like it’s much wider and vaster than actually being inside a gallery space”.

Aitken has visited Sydney several times, most recently about eight months before Covid-19 emerged. Planning the exhibition has taken about three years, and it has evolved continuously, with the works brought in from across Europe and the US. “I don’t like the idea that something is ‘fixed’,” he says, “I like things that are fluid.”

The survey has had to be put together in Sydney with Aitken issuing instructions via video conference from California. “This period has ushered in screen life that’s far more accelerated than would have happened without the pandemic,” he says. “But the counterpoint is that it has borne a greater interest and desire for physical, tactile, natural experiences than we’ve ever had. A really heightened experience within the landscape is almost fresh and new again.

“We come from a culture that rises with the sun and sleeps at sunset, that works off the land, and this period has divorced us from that in such an extreme way in these synthetic realities.”

For Underwater Pavilions, Aitken installed three geometric sculptures off the coast of California’s Catalina island in 2016. “The viewer had to swim into it,” he recalls. “You could swim or dive or snorkel, but you had to go under the ocean surface and occupy or swim through these large, floating, kaleidoscopic sculptures.

“I was thinking very much about that work when I was thinking about Sydney: it’s not only a city based on water, but it’s also based on tides and the sense of continuous movement, whether that’s different cultures or just the topography itself.”

Within the MCA, of course, Underwater Pavilions has to be represented in video form within spaces designed to represent coves and tributaries amid the lighting. Do traditional galleries have shortcomings, creating a need to subvert barriers between art and audience?

“I think there’s room for everything,” he says. “We can broaden our definition of what art is and can be. We can look at the spaces around us, whether it’s urban or remote and rural, whether it’s above us or below the ocean, whether it’s digital or a project that combines many different mediums. I think we’re going to see a revolution in what creativity and culture can be.”

I tell Aitken about our prime minister’s prevarication over attending the UN COP26 climate summit in Glasgow at the end of October, and our tenuous grasp of the goal of net zero emissions. Given Aitken’s works are ecologically minded, does he believe art has the power to change minds among people intransigent on such pressing questions?

“I don’t know, that’s a tricky question,” he says. He pauses. “I think art can sometimes be a door into a world, it can be an opening into a space that you are uncertain about. In that sense, it can truly expand the way you are seeing things, the framework and perspectives with which you see the world.

“For myself, some of the most powerful experiences with seeing an artwork have been moments where that work has shocked me, or it’s caught me off guard. It’s even been something I don’t necessarily agree with, but I find myself engaged in, and there’s this conversation that begins, and it grows, and you realise that piece of music, that film, that whatever it is in whatever media, actually is an agent of change.”

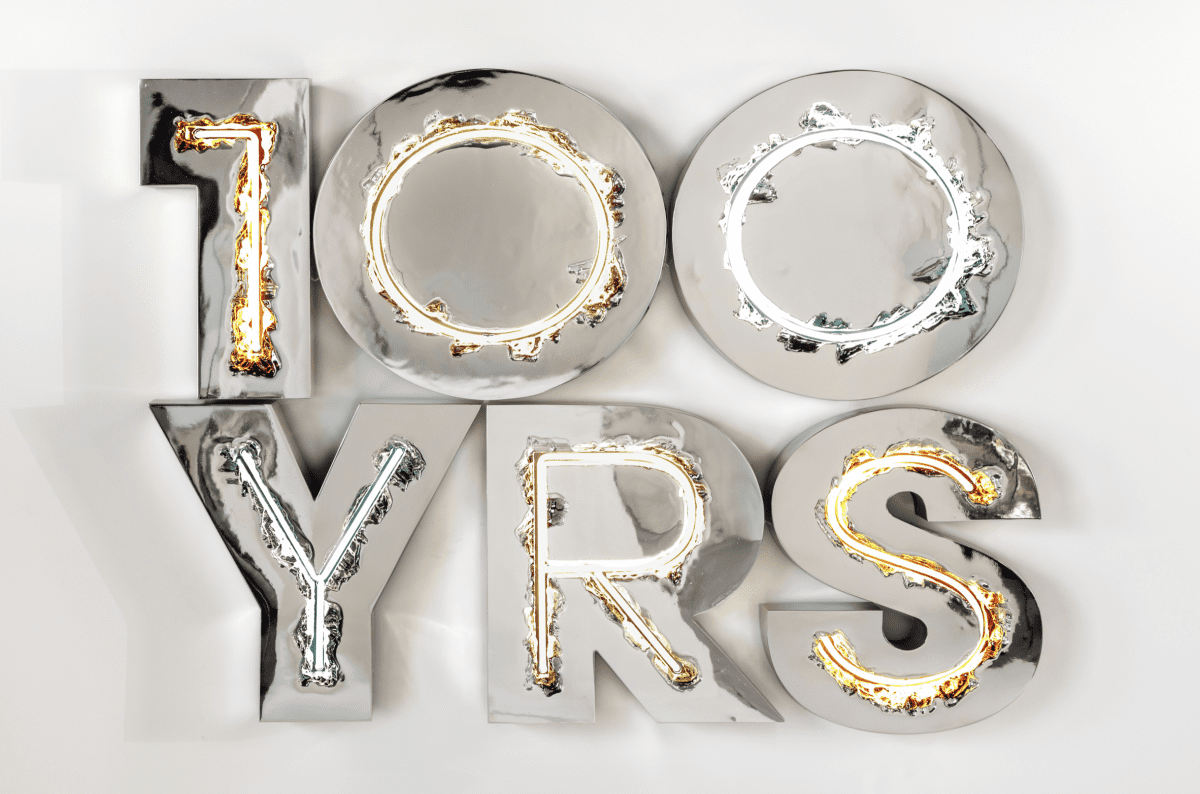

Doug Aitken: New Era

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

20 October—continuing into 2022