Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

When Jimmy Frank Juppurla and Joseph Williams Jangarrayi first went to a men’s art therapy group in Tennant Creek in 2016, they didn’t envisage how powerful making art might be for them. They certainly didn’t know about “brio”—an Italian word that suggests fiery vigour and mettle.

But these men had verve in abundance and before long they and the other men had formed the Tennant Creek Brio, a group that has come to be described by The Paris End as “one of the most exciting collectives in recent memory”. They’re making art resembling, as Artlink states, “insurgent guerrilla theatre”.

The Brio, a cross-cultural artist collective with about seven key members and numerous other collaborators from various local language groups, came directly out of that therapy group, led by Melbourne artist and former Collingwood AFL player Rupert Betheras. The group was part of an Anyinginyi Health Aboriginal Corporation program, which then moved to the Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre in 2017, where it officially became an artist collective.

The Brio now has such a strong reputation that Juppurla and Jangarrayi (known as Yugi) aren’t feeling daunted by the enormous spaces they’ve been allotted for their new Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA) survey show: after all, their work is dramatic, provocative and engaging enough to make an impact in any large space. It’s being billed, though, as a decade of work presented as “an ambitious, industrial-scaled, scenographic assemblage”.

However it manifests, these men explain the way their work has a focus on telling vital stories about themselves, their community and the bigger narratives of mining, displacement and colonisation, conflicting belief systems, contested histories and the need for collective action.

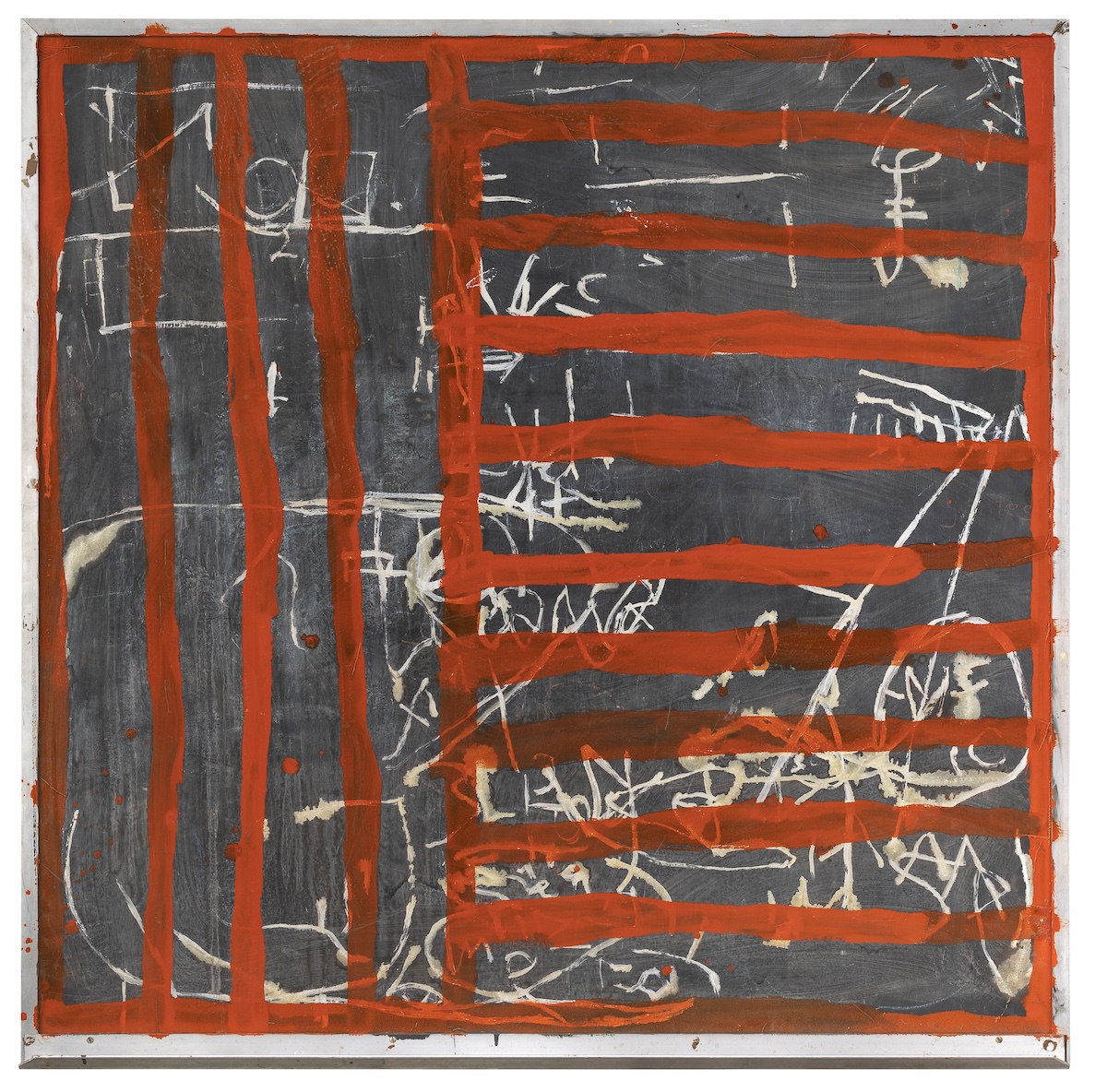

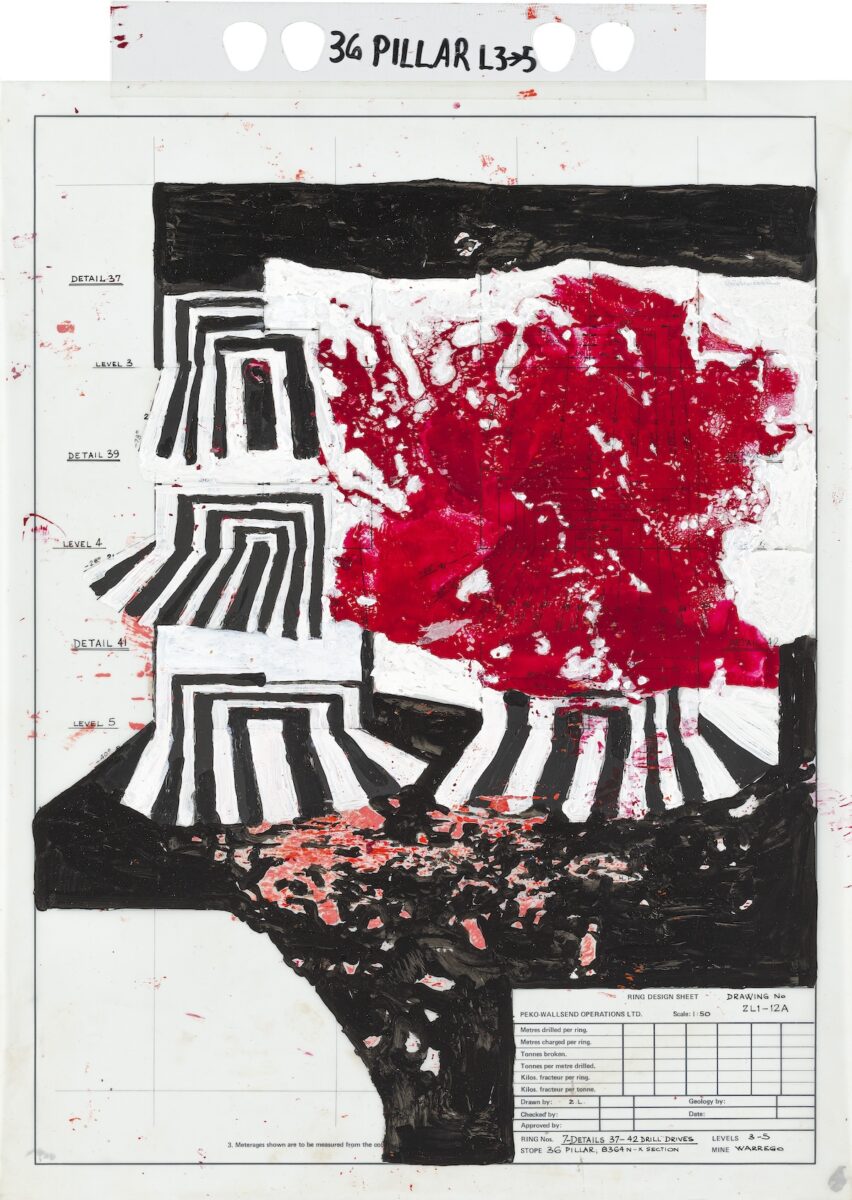

Speaking from Tennant Creek on Waramangu Country where they live and work, Juppurla and Yugi tell stories of the founding days of the Brio and how Betheras (a non-Indigenous member of the collective) initially inspired them to start using an extraordinary array of found materials in their work: salvaged items such as oil barrels, meat hooks, car bonnets, solar panels, poker machines, television screens, and geological maps from the region’s abandoned Warrego mine.

“We wanted to show the people who don’t really know this part of the world who we are,” Yugi says. “We were all just doing our own thing—whatever Rupert provided us with, we worked with. We had no thoughts of an art collective and becoming who we are today . . . In the men’s centre, in the backyard, we were just sitting all together and doing the work.”

One of his favourite ways of working is on the discarded maps, using charcoal, pencils, acrylics, and pens to express whatever he is feeling: “We are reclaiming the title back from the damaged Country, we are reclaiming and putting our people there.”

As Juppurla says, when mining began in the region, the corporations used the maps to mark out lines of ore, lines for boundaries, and lines for roads. “These big lines on these maps: but thousands of years before those maps and those miners there were other lines that we know—there were Songlines, there’s a dream line, significant lines for us. They put these lines on the maps without acknowledging the ones from before.”

Juppurla says the Brio’s founding drive has been for the men to express themselves about where and how they are living and the challenges involved with mining destroying the land and people being taken off Country and “moved about like sheep”. “A lot of mining happened on our Country with a lot of rubbish and materials that wasn’t there before. We wanted to tell about that disengagement from our Country and tell about how we felt about the impact.”

Turning those materials into a creative pursuit has been about bringing two worlds together—not just to contrast, but to critique and reconcile. One work, for example, is an old Tennant Creek nightclub poker machine painted over and pierced by traditional spears. As with most of their assemblages, there’s a complex array of ideas going on: repurposing, haunting and sending-up, with redemption, catharsis and complete anarchy at play.

Amid all this making, the Brio men have been excited about how strong an impact they have had on urban audiences. “Us fellas never thought art would be a powerful tool politically,” says Juppurla. “Melbourne, Sydney, these big places, a lot of people here in Central Australia wouldn’t dream of going there… that saying ‘when you are in the box you can’t see outside the box’: when you go out and look back you see the opportunities that are there for our people. That’s been true for the fellas. They live pretty hard lives on the outskirts of town. [The Brio] opened our perspective on how to tell our stories and express ourselves about how important our culture is.”

As Yugi observes: “We are showing the Tennant Creek community and the rest of the country that you can achieve anything you want to achieve as a group, whoever you are and whatever is happening in your life. And we are showing leadership and role models for other young men in our community, letting them know that it’s possible to carry on in life, be whatever you want to be.”

Tennant Creek Brio: Juparnta Ngattu Minjinypa Iconocrisis

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art

21 September—17 November

This article was originally published in the September/October 2024 print edition of Art Guide Australia.