Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

South Australian writer Zoe Freney met with painter Deidre But-Husaim to talk about their shared interest in the potential of bees, both practical and metaphorical.

I take a jar of honey to the Incinerator Studio in Adelaide when I go there to chat to painter Deidre But-Husaim about our mutual interests: bees and paint. The high price of honey is often conflated with the disastrous Colony Collapse Disorder phenomenon in America and dire predictions that honey bees may be another casualty of the Anthropocene. In Australia, expensive honey is due largely to seasonal climate variations and market pressures. But the honey in this jar was made by bees in a hive at my house. They work under my supervision but they are definitely not mine. They came to me almost by accident, through a series of coincidences. They are their own machine, efficient and of one mind.

On a fine day in autumn when the workers are out, I visit the bees to rob them. I’m wrapped in canvas and gauze, leather gauntlet gloves and leather boots, because I know I am the alien among them. I whisper, “Courage! Courage!” Mostly to myself, but also to the bees. The tone of the hive hum changes as I crack open the lid, and I know the bees don’t need my false courage.

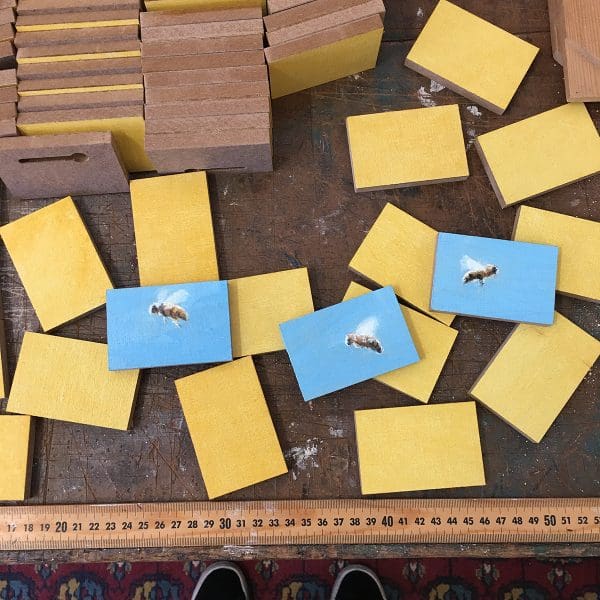

Deidre But-Husaim has been painting bees, working them out like little puzzles in paint, for several seasons now. The interest in bees began as a problem of how to paint them, not frozen and static, but described in their mysterious patterns of flight. This is how Deidre approaches most subjects. As she says, “It’s always about painting, about curiosity, about how to paint anything and make it work. I want to paint in such a way that the paint never apologises for being the slippery, difficult substance that it is.”

Bees throughout history have been praised as divine, noble and chaste, likened, in their virtue, to Christ and his mother, but also to earth-bound humans for their industry and social behaviour. However, bees have long occupied an ambivalent place in our imaginations. We farm bees for honey and wax and yet they are not tame. They are armed, swarming, uncontrollable. We are allergic to them, afraid of them, we exterminate them when they are inconvenient. Tending my bees is at once exhilarating and terrifying.

Deidre observes that painting too requires a certain relinquishing of control. She loves “the curious process of painting” but she admits that “paint is insurmountable.” As she explains, “I respond to both the formal aspects of the image and the material limitations that oil paint allows when applied to wood or linen.”

Deidre first began painting tiny bee works, oil on wooden panels 5 x 7.5 cm, as tests for a larger swarm painting. Now individual bees have been sent to collectors all over the world, like outriders scouting ahead of the swarm. In the larger work, Tinnitus, 2017, Deidre sought to create a multi-sensory painting. This work is effective in calling up the hum and the prickle of a mass of moving bees. The surface is immediate and fresh, leaving, as Deidre says, “space for my thoughts and for viewers to fill in the gaps.” The title of the painting internalises the buzz of bees to a ringing in the ears. Indeed, Deidre shows me her source images, photographs of competitors in the Chinese bee wearing competition, their bodies blurred by bees, reminding me of Sylvia Plath’s poem, ‘Stings’:

The bees found him out,

Molding onto his lips like lies,

Complicating his features.

Plath was a beekeeper. Her sequence of bee poems describes her relationship to the bees, to herself and to the world. Tending a hive has given me a new awareness of being in the world. I challenge my previously understood relationships to nature, nurture, fear and agency. And while Deidre says that for her the bees began as a problem in paint, how to apply paint “in a way that suggests movement, flight and fragility,” this series has led to other discoveries.

Honey bees have become a symbol of dystopic anthropogenic futures. With unexplained mass bee deaths in America since 2006 (and to a lesser extent in Europe) the health of our agricultural and environmental practices has been questioned. Deidre’s bee paintings were in part generated by a desire to engage in environmental and socio-political issues and she tells me that her study of bees in paint was paralleled by a study of their lives and habits, and the ways that humans exploit them. Folklorist, Austin E. Fife, reports that in medieval swarm charms, the bees were endearingly called “victory women.” But these ferociously armed female workers are asked “not to fly to the wood but to sink to the earth and to work for man.”

Bees working for the man in commercial hives are in great demand as pollinators. Deidre has recently been to China, where hives for hire earn apiarists more money than honey. Ideas about pollination, along with photos brought back from her China trip, have led to a new group of paintings that focus on bees as pollinators with human handlers.

Deidre explains, “I don’t set out to make a body of work but just start a work and respond to it as it develops, both materially and formally. Paintings go out and exist on their own in the world, so they need to have their own weight.” The China paintings seem to be about weight, as bee boxes are stacked and piled on carts and bicycles. There is a precariousness to the project of the pollinators, as stacks threaten to slip and tumble. There is a sense of the weight of human responsibility as swarms of bees are herded and swept, barely restrained. These small works carry weighty metaphors of human meddling in natural systems.

These days, Deidre lets paintings come to her, often from photographs she has taken and collected over many years. “As I work the image will often change as the painting requires. Some elements will be fictions, and possibly impossible.” The paintings are inspired by a painter’s deep engagement in life. Deidre recounts how walking through the night in Shanghai she passed Buddhists chanting on the banks of the river as they released fish for karma, and a group of women doing disco tai chi under street lights. There’s really no need to seek subjects for paintings; if you notice the infinite ways of living life you will always have enough.

In the end the bees came to Deidre too, a swarm taking up residence in the chimney of the studio while she worked on the bee paintings. The honey bee has been a rich metaphor since ancient writers described them with wonder. Pliny the Elder called bees the “most noble insects,” and Biblical texts tell humans to emulate the virtues of bees. Today the current plight of the honey bee may signal to us all that is wrong in the world, and remind us that we are poor custodians here. Deidre claims she began the bees simply as a test, how to handle paint in describing masses of tiny moving objects. It may have begun as an exercise in paint, but the bees had other ideas.