Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

A multi-disciplinary artist of Worimi descent, Dean Cross utilises installation, sculpture, photography and painting to combine national and personal histories. Recently announced as one of five artists in Primavera 2021 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, in 2020 Cross became the inaugural recipient of Goulburn Regional Art Gallery’s The Good Initiative. As a result, Cross developed Icarus, my Son. In the Greek myth, Icarus leaves home and flies too close to the sun – with fatal consequences. In his exhibition, the Sydney-based artist explores the pressure young people feel to leave regional locations to further their artistic careers. Cross spoke to Briony Downes about creative ambition and the links between his own experiences and his current solo show.

Briony Downes: Can you talk me through the work in Icarus, my Son and how it came together?

Dean Cross: Goulburn Regional Art Gallery director Gina Mobayed has been really adamant about the need to commission artists to create new works and to have these presented in a regional location first, before a metropolitan setting. After its time in Goulburn, the show will travel to Carriageworks in Sydney.

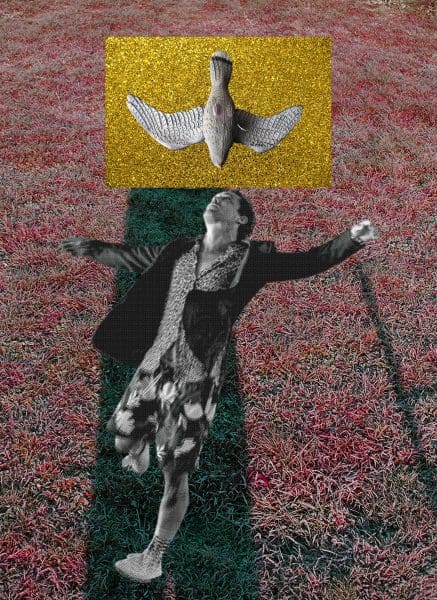

One of my early methodologies that I wanted to work with was based around exhibition space as psychological space. There are four distinct works: a video piece, a large-scale photographic canvas and two smaller wall-based sculptures. All the materials I’ve used are found materials.

I wanted to make a show anybody could make, you don’t need fine hand skills to produce any of the work. With the wall-based work, one of them is a second-hand cricket bat that I’ve crudely carved into an arm with the same dimensions as my right arm. The other is a 1950s Namatjira print that has been hanging in my mother-in-law’s laundry for 40 years, slowly fading.

BD: What is that saying?

DC: I’m not that interested in making statements, but when put together in the space the works are like a tapestry. Each piece informs the whole.

I often describe my work as a type of parataxis, which means a sentence that can still be read without every word. While each of the works are loaded with their own histories, it’s not so much about what the individual works mean, but more about how they operate together within the space.

Obviously a faded Namatjira print is a heavily loaded object, there’s heaps of meaning there. That’s how a found object operates, it’s the same with the cricket bat. I’ve gone through my own processes with how I’ve used the objects, but I’d be reluctant to pin down what they are trying to say.

BD: How does the Icarus myth tie into this body of work?

DC: When I first started thinking about this show, I kept thinking about a back shed I used to have on my property, and the memory of it being destroyed during a storm. Its destruction and Icarus’s fall coalesced in my mind. Icarus’s story became a useful scaffold to build my themes around, but then the real protagonist became Daedalus, his father. By the time the exhibition landed in the gallery, I could see it was about both. The show is quite personal, and I am both Icarus and Daedalus in this strange world I’ve built.

BD: A core theme of Icarus, my Son is the idea that young people need to leave regional areas to make it big in their careers. How does this relate back to your own experience?

DC: When I came to put together my application, I asked myself why I wanted this opportunity. One of the things I thought about was my relationship to Goulburn and the region [Gandangara Country]. I thought through how common it is for young people to have to leave to pursue artistic goals, as this was certainly the case for me.

Before I started in visual arts, I was a contemporary dancer and choreographer. I definitely couldn’t do that professionally where I am from [Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country], so I knew I had to make the decision to dislocate myself.

With Icarus, my Son, I wanted to question whether or not those processes are still serving artists. How much do we want to be living in a world where you have to leave where you are from, where you belong, to pursue these so-called goals?

BD: What answers did you uncover?

DC: I will often say a good artwork never has any answers, it only asks questions. Personally, I think the metropolitan-centred hierarchy we’ve developed is problematic. There is this West-is-best attitude, especially in colonial countries. For dancers, unless you’ve been to Europe, you weren’t worth your chops. It’s similar with visual arts. We still have this provincial hang-up about Australian artists – there’s only so far your ambition can take you on our island. In one way or another, we all have this feeling lurking behind us.

Whether I have any answers, I’m not really sure, but I think it’s important to drill down into that narrative and ask ourselves if that’s what we really want or if that’s how it needs to be.

Nothing needs to be the way it is, everything can change.

BD: In the exhibition statement you speak about confronting ambition and evaluating your role as a 21st century culture-maker. What did you decide your role is?

DC: An important one; I approach it with great responsibility. As our world continues to feel more and more unstable, I think it’s through culture that we come to understand ourselves in the past and present. Icarus thinking and culture-making are separate in a way because I had to think long and hard about my own ambitions.

This show has really confronted me about what my goals are – what really do I want and is it realistic as an artist in Australia? The role of a culture-maker and artist is just to keep going. That’s all you can do, keep working and not worry too much about so-called success. There is no gold standard.

BD: Your father Mike Cross selected a work from Goulburn’s permanent collection to display in The Window gallery for the duration of your exhibition. What did he choose?

DC: It’s a Sydney Long aquatint print called The Lagoon, 1928. Long was born in Goulburn 150 years ago and his life perfectly played out this same pathway. He did all the right things as an artist and ended up in London having a celebrated career, as did many of those late 19th century artists. Now many of our great contemporary artists still follow that pathway to New York or London. Whether or not my father realised how neatly the artist he chose fit into the meta-narrative of my show, I’m not 100% sure, but it wouldn’t surprise me.

Icarus, my Son

Dean Cross

Goulburn Regional Art Gallery

17 July – 28 August

Carriageworks

5 November – 30 January 2022