Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

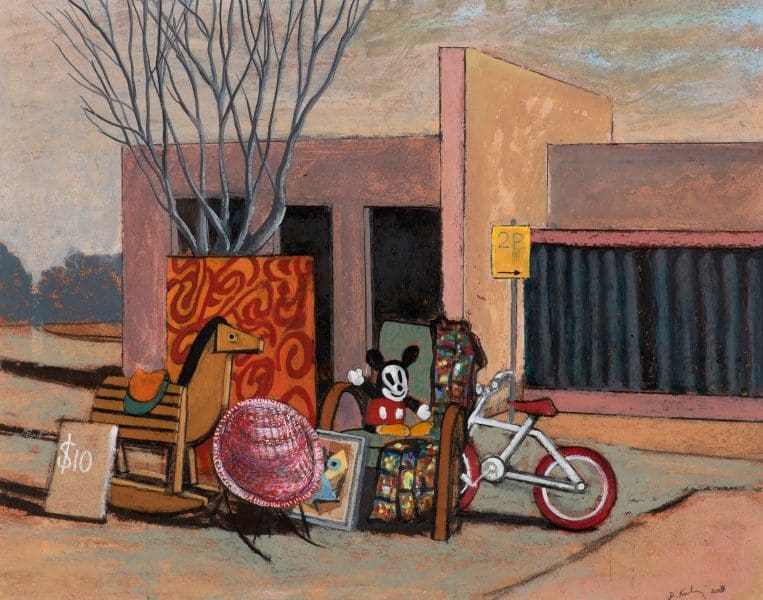

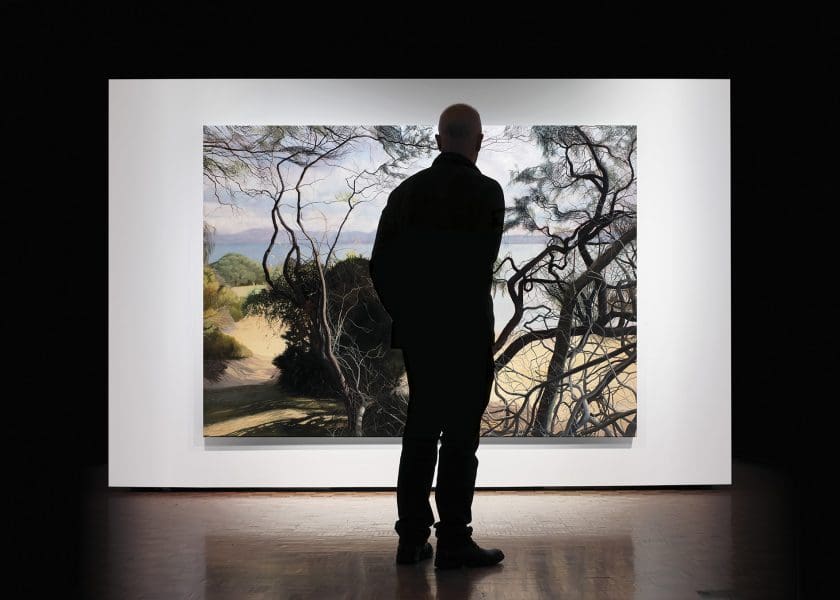

David Keeling’s colonial predecessors painted the Tasmanian landscape as a picture-postcard place ripe for cattle, pasture and intrepid settlers. These romanticised paintings – which advertised the false notion of terra nullius, a Latin term meaning ‘nobody’s land’ – are not views Keeling is comfortable with. For Keeling, the landscape is indeed a place of great beauty, yet it is also a contested site, scarred by immense historical trauma and greed.

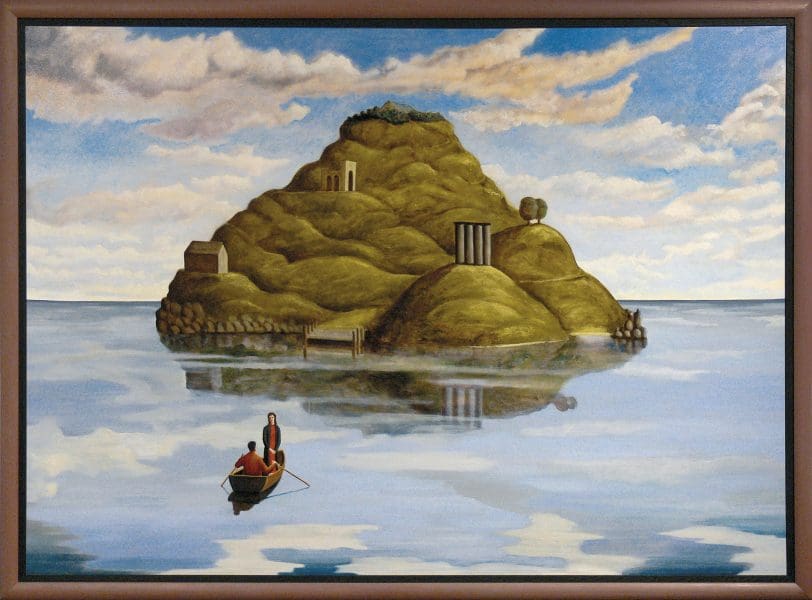

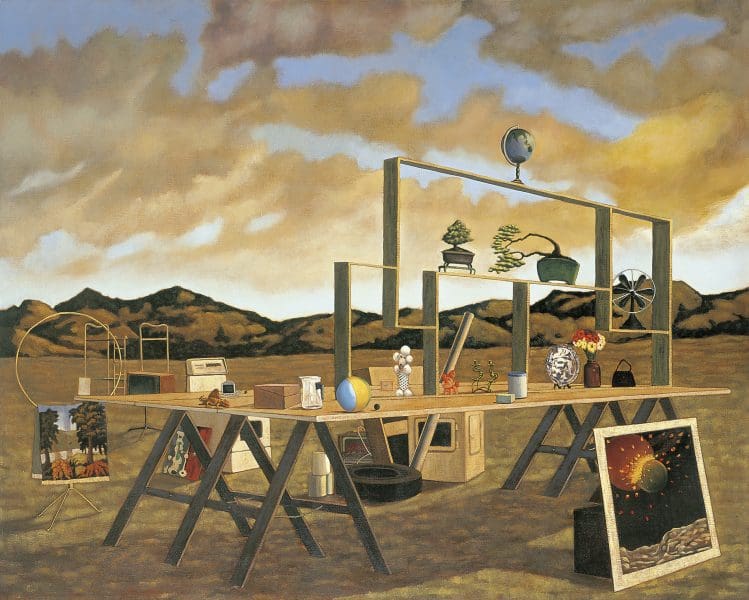

Stranger, at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (TMAG), is a survey show which offers an insight into the way Keeling sees Tasmania. Possessing a style influenced by surrealism and symbolism, particularly the work of Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico, Keeling paints tightly framed, close observations of the landscape and has worked across four decades to understand the narrative of place and the consequences of human impact. Keeling’s canvases document the parched hills of the Tasmanian Midlands, the crystalline waters of the East Coast and remote pockets of national parks.

“When I came back to Tasmania from Sydney in the 1980s, I made a very conscious decision to make work about where I lived,” he says. “In a way, it was a counter to the international movements I saw all around me when I travelled. I wanted to be rooted in a place and to start telling its story.”

With 70 works divided across four galleries, Stranger is not a linear progression. Instead it draws connections between Keeling’s work and its persistent link to ideas about industry, conservation and the sublime.

“We have a really grim history we need to come to terms with,” Keeling explains. “There are these moments in landscape that are so powerful and so beautiful. We can go past something we’ve seen a thousand times and then one day you go past and really see it for the first time. It’s a beauty worth preserving.”

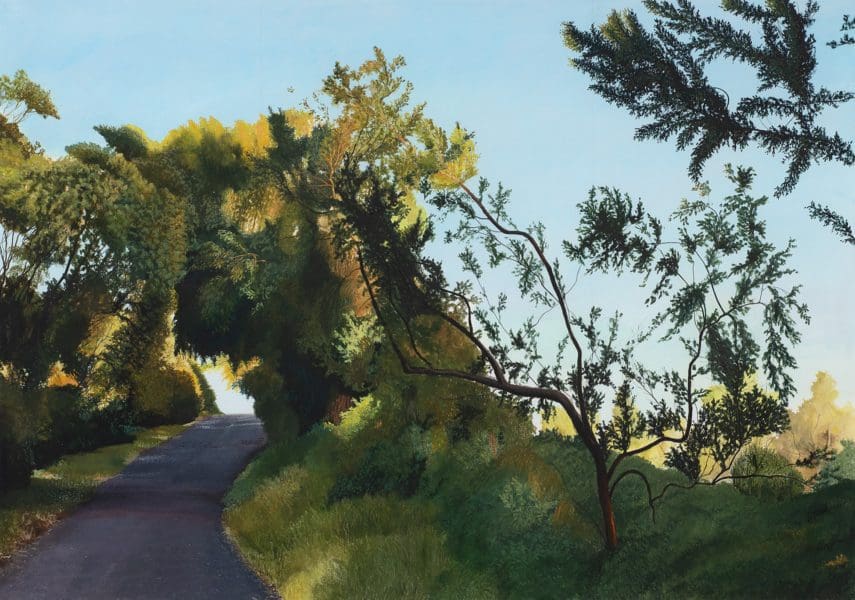

The artist’s responses to the landscape of Narawntapu National Park, in the central north of Tasmania, takes up a sizable portion of Stranger and comprises work mostly created in the last decade. It is a place that remains close to his heart.

“The thing I love about the coastal landscape is the trees, in particular the she-oaks and the blackwoods,” Keeling says. “As an antidote to the romantic, big vista, white male approach to the Tasmanian landscape, I attempt to understand the details of nature. The Narawntapu paintings really try to analyse the way the light falls in all that dense detail of branches. In Tasmania it’s rare to have a completely cloudless day, so we suddenly get these spurts of light – like parts of the landscape have been spot-lit. That’s what I try to give voice to.”

Interspersed between the paintings are Keeling’s three-dimensional pieces – elegant arrangements of twig-like wooden sculptures and hand carved curios painted with miniature landscapes. Also included are the small paintings on wood Keeling wrapped in a tea towel and took to prospective galleries in the early days of his career. A number of sketchbooks offer an intimate look into Keeling’s daily creative planning and the compositional studies for many of the paintings in the exhibition. And his longstanding connection to TMAG (and Tasmania’s history) is also evident in the frequent references to items from the museum’s collection within his paintings – taxidermy animals, Governor George Arthur’s Proclamation Board (c. 1828-30) and Fanny Cochrane Smith’s recorded song, the only spoken record of an original Tasmanian Aboriginal language.

David Keeling also has an exhibition of works on paper on show at Bett Gallery.

Stranger

David Keeling

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

20 November – 14 February

Parallel Lines: drawings from my archive, 1992 to 2021

David Keeling

Bett Gallery

15 January – 13 February