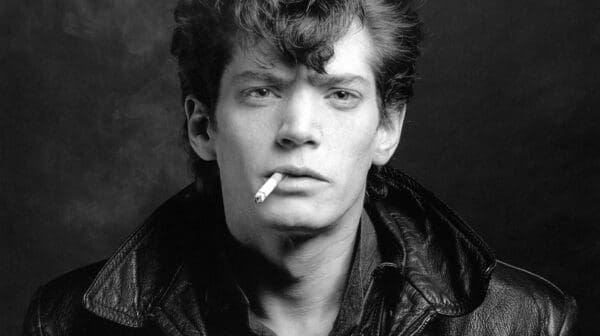

A shift has taken place in the studio of Sydney-based artist David Fairbairn. Large baths of ferric chloride have been installed. Stacks of copper plates and all manner of implements (blades, sanding discs, an angle grinder) are arranged beside the easel. Known for his massive drawings, Fairbairn has extended his raw, linear approach to portraiture into the realm of printmaking. His exhibition Drawn to Print couples existing drawings with these new printed works. Sheridan Coleman asked Fairbairn to unravel his approach to portraiture and to discuss how he knows when a work is finished.

Sheridan Coleman: Drawn to Print includes two portraits of each sitter, made several years apart. How significant is time in your work?

DF: I’ve worked with these subjects for the last five to ten years. When you spend all that time with a sitter you develop a strong relationship. My etchings are also very much about time, because they’re constantly being modified. Each time I come back to the sitter, their reality keeps changing. The same person, at different times of day, different months, produces different results. That’s why I don’t work on one piece, but on a body of work. Images emerge from it where I’ve gotten closer to being able to fix that target.

SC: Printmaking can be an unpredictable medium. Was this something that attracted you to it?

DF: With printmaking there is a delayed reaction, between marking the plates and the actual printing. That creates less self-consciousness. You don’t really know what’s going to happen in the acid bath. You don’t have the control you have with drawing. It requires a lot more faith. I really didn’t want to go down the path of polite printmaking, so I have been reacting to each proof by working back into the image. I want to be able to get situations happening on the copper that are like taking an eraser to the paper of a drawing, and obliterating it and rebuilding it. The process is a bit ritualistic, taking the work through the proofing stages and then attacking the copper sheets again and so on.

SC: Your drawings are richly coloured, whereas your printsare black and white. Why the move to monochrome?

DF: There’s nowhere to hide. If the quality of the mark making doesn’t stack up, it’s very noticeable, because it’s stark, cleansed of extraneous information. With painting and drawing you can get caught up in the complex process of applying the material. Colour can seduce you or obscure the underlying elements of the image. Black and white has been a form of exorcism; it takes everything away but the underlying structure of the mark making process.

SC: Your portraits provide us with a glimpse of your studio. How does location figure into your portraits?

DF: Most of the portraits are about trying to inhabit this psychological space, what I call the ‘oxygen and air’ that circulates around the portrait. Sitters come to the studio, where there are other drawings on the wall, which interact with the subject and appear in the etchings. That sense of place and of space is important. I guess it’s that modernist conceptual framework where you’re getting things moving behind the picture plane, or on it, or in front of it. Living in the Georges River catchment area has also influenced my work. It’s all gullies and wild bushland. There’s some subliminal relationship to the idea of contours and terrain. The large works are two or three meters in scale, and I tend to look at them like maps, or as things you might walk across.

SC: What does ‘line’ mean to you?

DF: Line is one of the ways of constructing. It’s language. You’ve got mass and you’ve got line. I’ve always seen the sole use of line as very abstracting. An analogy would be a building without its cladding, an open-ended, skeletal structure. I’ve always thought of my portraits like that: the skin stripped back so you can enter the work. The lines accumulate as I work directly onto copper sheets, and out of those lines, the image appears. For me, line is only one aspect of the proposition. That’s the challenge, to make the image stand out using only one part of the language.

SC: You produce your prints yourself, from etching plate to finished print. What’s behind this decision?

DF: I have worked with master printers, but printmakers at that level have a particular way of printing. You can tell, across different artist’s work, which printer it is. I wanted to do the etchings myself. The process you use is ultimately unique to yourself: you make them the way you make them.

I like it a bit more grungy. Some of the portraits verge on disintegration. I remember the artist Gareth Sansom once described that propensity for artists to “tidy things up”. I like that sense of raggedness, of not being too polite. Too much work is removed from the real person that made it.

SC: You often work back into your prints several times. How do you decide when a work is finished?

DF: When it seems to detach itself from you. When you come in and the portrait is a fully completed person, standing separately. That’s very much an internal feeling. Usually you end up abandoning the work. You try a multitude of different ways into the image, and over time, from sheer experience, you just know when you’ve got something interesting, and the trick is to recognise that.

Drawn to Print: David Fairbairn

Lake Macquarie City Gallery

21 October – 3 December 2017

Orange Regional Gallery

17 February – 1 April 2018

Coffs Harbour Regional Gallery

13 July – 8 September 2018