Please note that due to COVID-19 restrictions, David Claerbout’s exhibition Olympia is postponed and Samstag Museum of Art is currently closed. Continuing our commitment to covering the arts Australia-wide, Art Guide Australia will continue to share articles and stories on artists and exhibitions during this time, encouraging viewers to experience art online.

David Claerbout’s project Olympia, a digital rendition of the iconic Berlin stadium going to ruin over the course of a millennia, won’t be finished in his lifetime. In fact, since it started in 2016 it won’t be finished (in theory) until 3016, a year so distant it’s almost unimaginable. So you’d think the temptation to give the algorithm a nudge—to speed things up and indulge in a spot of virtual time travel— would be almost irresistible. But the Belgian artist insists that even suggesting such a thing is to miss the point.

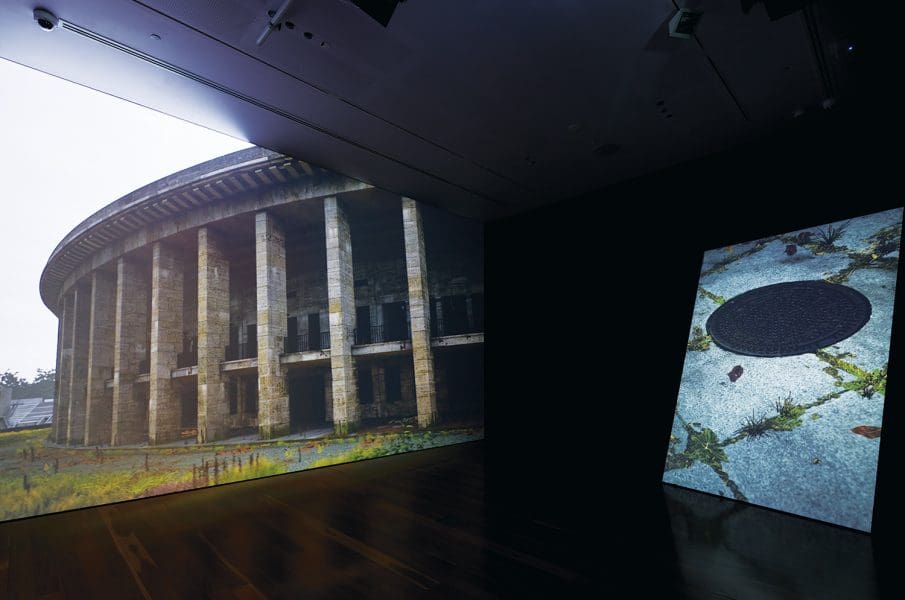

Olympia underlines the non-human inexorability of time. “We love to compress time, it makes us feel as if we can exercise power over time,” Claerbout says. “But all we do, really, is obey a ‘monochronic’ view on time; that of the clock, either faster or slower.” In Claerbout’s multiscreen installation, a carefully rendered digital recreation of the stadium ages in real-time. Data is collected from the local weather bureau and this information—sunlight hours, rainfall, temperature—is used to regulate the growth of the hypothetical plants that can already be seen springing up in cracks in the concrete, just four years on. In this way Olympia highlights the simultaneity of different temporal streams: our own all-too-brief lifespans, the slow degradation of stone, the surprisingly rapid growth of plants.

The stadium was built for the 1938 Olympic games. It is often cited as a good example of Nazi architect Albert Speer’s notion that public buildings should be designed to produce aesthetically powerful, monumental ruins. When asked why, of all the Nazi-built structures, he chose this one for Olympia, Claerbout says, “I have a strong impression that it was the building that chose me, probably helped by it being a sports venue right before it became a propaganda tool.”

Olympia

David Claerbout

Samstag Museum of Art

This article was originally published in the May/June 2020 print edition of Art Guide Australia.