Reframing a Collection

Drawn from the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art at the University of Western Australia (UWA), Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery’s show Place Makers, reframes the artists—who just happen to be female.

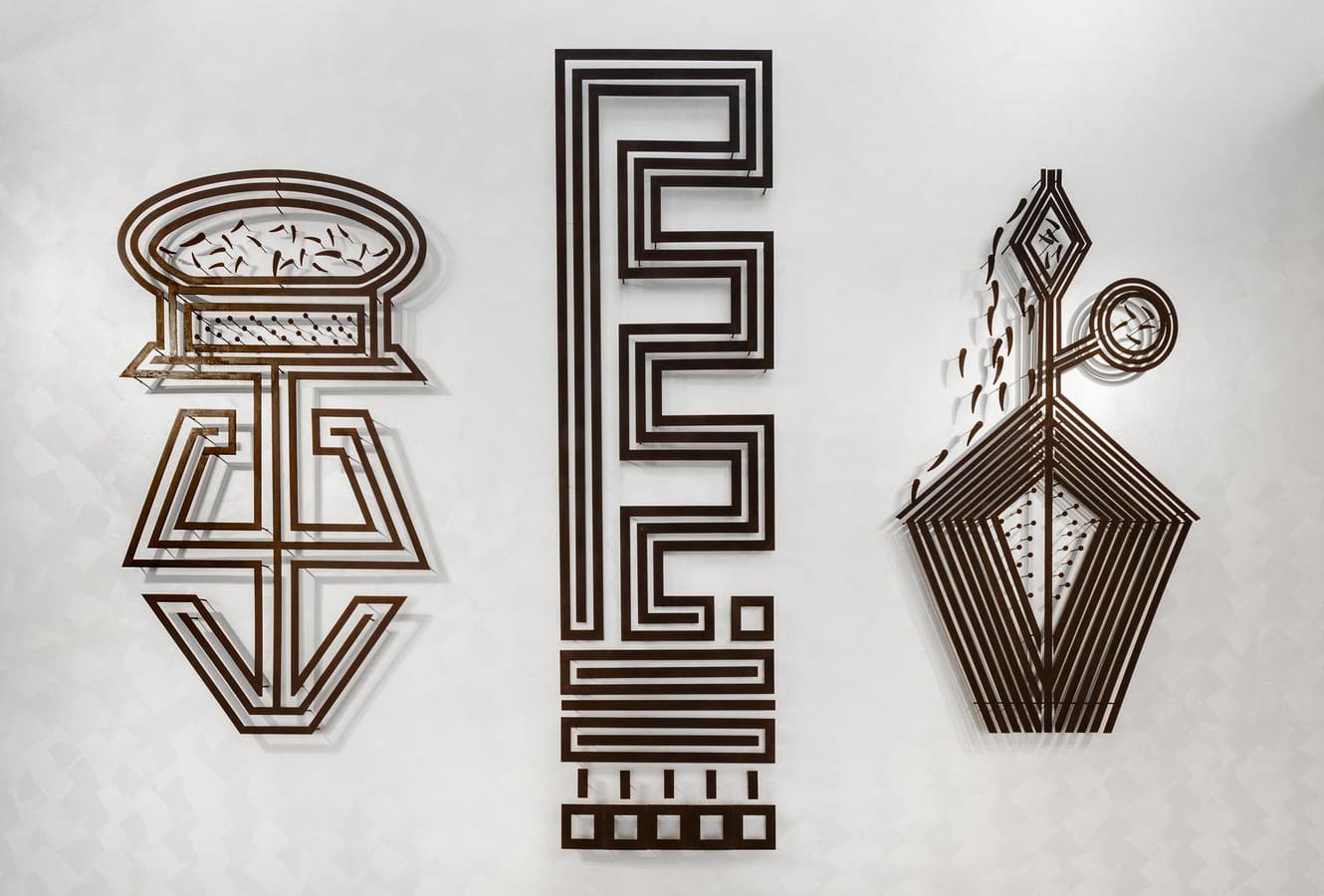

Darrell Sibosado at the Biennale of Sydney 2024 at White Bay Power Station. Photo by Daniel Boud.

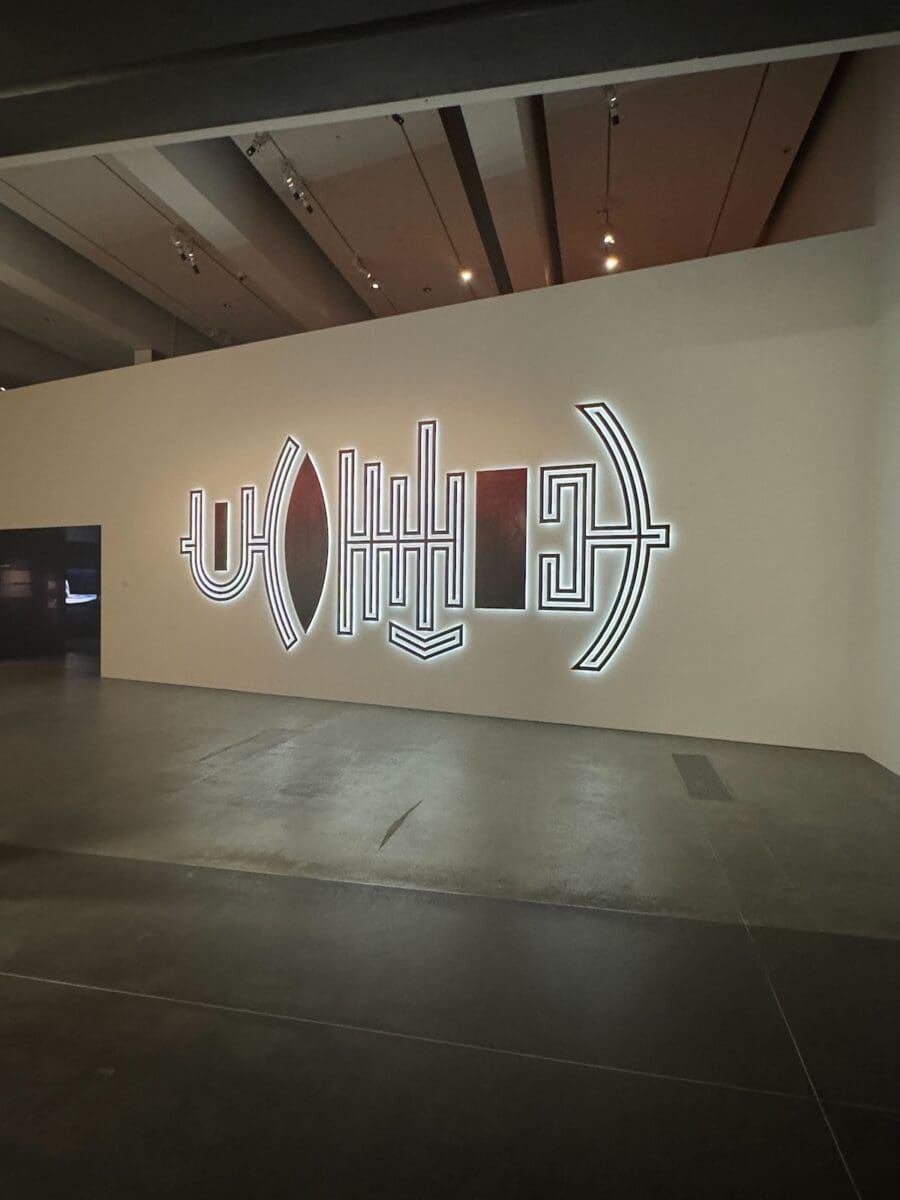

Darrell Sibosado, Ilgarr (blood), 2024, composed in enamelled steel and backlit with neon LED, 1000 x 300 cm, edition of 2 + 1 AP. Collection of Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Installation view at The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art.

Darrell Sibosado, Ilgarr (blood), 2024, composed in enamelled steel and backlit with neon LED, 1000 x 300 cm, edition of 2 + 1 AP. Collection of Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Installation view at The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art.

Darrell Sibosado with his work Ilgarr (blood), 2024, composed in enamelled steel and backlit with neon LED, 1000 x 300 cm, edition of 2 + 1 AP. Collection of Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art. Installation view at The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art.

Darrell Sibosado has exhibited as an artist for less than ten years, but the high-profile opportunities currently coming his way reflect not only an innovative vision drawn from his Bard people’s traditions, but his experience as a long-term participant in the art scene. He was born in 1966 in Marapikurrinya/Port Hedland, going on to live and work in Sydney from the 1980s. There, he discovered luminaries associated with the legendary Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative including Tracey Moffatt and Michael Riley. He also studied performing arts at NAISDA College with Stephen and Russell Page, and Frances Rings, working in music, film, television and performance. When he moved home to Lombadina on the Dampier Peninsula in the Kimberley region ten years ago, he got serious about his own artmaking, pursuing the ideas that had been “sitting in my mind for years.”

Currently showing Ilgarr (Blood), 2024 in Brisbane’s 11th Asia-Pacific Triennial, following a major commission last year for Ten Thousand Suns: 24th Biennale of Sydney, and working toward this year’s Bangarra Dance Theatre’s production Illume as artistic and cultural collaborator, Darrell Sibosado spoke to Louise Martin-Chew about using scale to elevate Aboriginal culture and his pearl shell carving traditions using contemporary materials.

Louise Martin-Chew: How did you find your way to making your own artwork relatively recently?

Darrell Sibosado: My people on the Dampier Peninsula, Bard people, are traditionally pearl carvers, and I’ve always carved. Our male uncles taught us. I have always wanted to use our designs, elevated with scale and materials like steel.

LMC: How did the opportunity arise?

DS: My brother Garry and I were approached by the Art Gallery of Western Australia to make work for a survey show on the Kimberley called Desert River Sea: Portraits of the Kimberley in 2019. Garry and I made the same story, but he did it in mother of pearl and I did it in metal. Before that I spent 30 years in Sydney, where I did a print workshop at COFA (College of Fine Arts), and made small designs but my career path was in the promotion, curating and management of other artists.

LMC: Your work is large scale and expressed in non-traditional media and has attracted attention with its dynamic aesthetic and abstract qualities.

DS: It’s driven by my idea that our motifs, style and designs would look very strong in large scale. Big. My intent was also to get our Bard visual language on the scene, to make our culture and language more accessible. Traditionally mother of pearl carving is done on a small scale, mostly collected by museums and large institutions. This work has been sitting in my mind for years, waiting for the right opportunity.

LMC: Your works are often illuminated, often 15 to 30 metres long. How do you hope they are read by audiences?

DS: They’re in the language of my people. In the work, there are traditional designs that I can’t be too explicit about. It’s part of an ongoing tradition; these designs that I’m doing now become part of my family’s design. The work I do is specific to my family, but the geometric and maze-like patterns I use very large are traditionally seen on the surface of the pearl shell and may be worn by men in ceremony to cover the pubic area.

LMC: The recent major works tell aspects of your story, with Ilgarr (Blood) a translation of the riji pearl shell markings which relate the discovery of blood by Bard ancient beings and its relationship with your lore.

DS: Some aspects of these stories I’m not allowed to talk about. That’s why I’m using designs with scale that create them as something else. Ilgarr (Blood) is about our [Bard] relationship with blood and how it came about. I refer to a particular ancestor, who introduced ceremony and ritual around blood. It’s about scarification and the letting of blood. In that story, he got poked by a stone fish and the pain led into the ritual, which explores why we have bloodletting, why we scar ourselves and—there’s more to it—our ceremonies around blood.

LMC: Did your Biennale of Sydney work, Galalan at Gumiri, 2023, also walk a fine line between what it means for you and what can be shared?

DS: Yes. These are the designs and stories we live by. That work is about one of our most important ancestors, Galalan, who gave us rules about what to take [from the natural world], how much to take, and how to distribute. They’re rules we live by to this day. It’s also from a sacred place—from where my clan and my people are directly descended. It’s the birthplace of our people.

LMC: It is materially similar to Ilgarr (Blood), using steel and LED lights.

DS: I’m interested in materials used in construction; the intent is to make it last forever, a balance of longevity and ephemerality. I started with Corten steel, I really love the rusty metal look, and I also fantasise about these things just rusting away eventually, powdering into the ground.

LMC: This year you are developing a work with Bangarra Dance Theatre that explores the importance of light to Indigenous culture.

DS: Illume premieres in June, and Bangarra work in a very collaborative way. They’ve already been out to WA where I’m from, and they’re coming back with the creative team in February. I want to incorporate the moving image amongst the dancers. Light is used to examine the impact of light pollution and climate change on my Country. I hope that this work will vibrate like my Country vibrates.

LMC: What do you see as your greatest achievement so far?

DS: The Biennale of Sydney work, given its 15-metre scale and getting the concept out of my head, and the collaboration with Bangarra. Most important is making people open their eyes to realise that there are so many different Aboriginal visual languages. I’m off to the India Art Fair in February and I’m interested to see what the international audiences see in my work.

The 11th Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art

Queensland Art Gallery | Gallery of Modern Art

30 November—27 April

Illume, Bangarra Dance Theatre

Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House

4—14 June