A forbidding ruined castle on a windswept moor, illuminated by lightning. Rustling black skirts, a memorial locket, a bracelet made of hair.

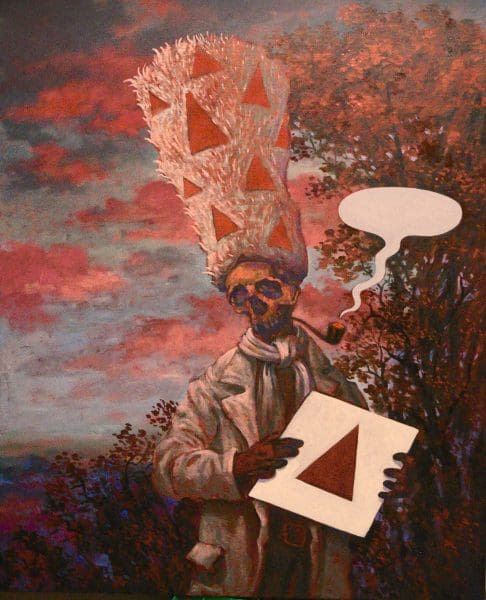

With their roots in 18th and 19th-century novels, the tropes of the gothic remain strong in our cultural imagination. In Bendigo Art Gallery’s exhibition Gothic Beauty: Victorian notions of love, loss and spirituality, works by key contemporary artists including Bill Henson, Sally Smart, Kate Just, Julia DeVille and Simon Pericich are set against gothic literature, Victorian mourning jewellery, pre-Raphaelite paintings, and even a 19th-century wooden hearse, formerly used by Bendigo’s undertakers.

The exhibition draws from the gallery’s extensive and varied collection, as well as loaned items and a number of newly commissioned works.

As curator Tansy Curtin says, the show aims to track “the history of the gothic novel through to Romanticism, medievalism, spiritualism, and the Victorian gothic with its history of mourning ritual.”

Gothic literature and symbols merge medievalism, Romantic imagery, and horror. Originally, ‘gothic’ refers to a style of 12th-century architecture, all spires and vaulted ceilings and gargoyles; 600 years later these buildings were represented in literature as dark crumbling ruins, with terrors lurking in their depths. Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto, published in 1764, is considered the first gothic novel. What followed was an era that gave us Dracula and Frankenstein, setting the savagery of human emotion against stormy nights and craggy landscapes.

Influencing art, design and architecture, the gothic style overlaps Victorian England’s obsession with death and mourning rituals. Gothic Beauty contains a wealth of period mourning objects: heavy black dresses (for both children and adults) on loan from the National Gallery of Victoria collection, there are also rings engraved with initials and dates; enameled brooches and lockets; miniature portraits on ivory. Perhaps the most striking piece of jewellery is a finely-worked bracelet, its braided cord band woven from human hair. In a time of precarious mortality, these keepsakes were designed to hold a loved one physically close.

One element running through many works in this exhibition is, as Curtin puts it, “the gothic as a feminist notion.”

The genre enjoyed huge popularity among middle and upper-class women, both as readers and writers. Perhaps the dramatic settings and unfettered emotion – the possibility of a forbidden thrill – offered something of a reprieve from repressive society.

“What was it about the gothic that enticed women?” says Curtin. “Of course, it’s escapism, leaving the humdrum lives that they had – and also the thrill of it, the excitement, the romantic side. A kind of pleasurable terror.”

In Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, itself a satire of the genre, the heroine Catherine Morland is a young woman obsessed with gothic novels. One scene sees Catherine find the key to an old desk and unlock it, “hoping to find some incredibly mysterious information,” as Curtin says. (In fact, all she uncovers is washing bills.) The trope of the key is a recurring one in gothic literature, conveying the possibility of unlocking secret knowledge or places unknown.

Taking the form of the key and connecting it to the psyche is Kate Just’s series of epoxy resin sculptures, from the 2010 installation Her Keys. Black and sombre, these oversized forms convey hieroglyphs or runes as much as keys, an intimate language of inward escape.

The motif of the crow or raven, both mythologised as harbingers of doom, occur throughout the exhibition: in new work by Michael Needham, in Sally Smart’s Crow (Shadow Farm), 2003; and in Michael Vale’s macabre paintings set in forbidding landscapes. A looming black bird of indeterminate species spreads its wings in Simon Pericich’s 2013 sculpture The Full Moon Rising Over The Suburban McDonalds Spelt Out The Word ‘OM’: the wings unmistakably form two rounded arches.

Crows also flock in the air in Tracey Moffatt’s Invocations #5, from a silkscreened series dealing with ideas of “witchcraft and feminine power,” as Curtin says, against the backdrop of the Australian desert.

It also references Hitchcock’s The Birds, an example of contemporary gothic. In this setting, however, the image of the crow is complicated: within many Indigenous traditions, the crow (or, more correctly, the Australian raven) is significant not as a bringer of death but as an important totem, one half of a universal balance.

Finally, a glimpse into gothic futurism is presented in Jess Johnson’s 2014 video Mnemonic Pulse, a mesmerising loop of hyper-realistic computer game style graphics with elements of horror, abjection and medievalism. This work points at once forwards and backwards, linking the architecture of a thousand years ago to its current and future legacy.

Gothic Beauty: Victorian notions of love, loss and spirituality

Bendigo Art Gallery

6 October – 10 February 2019

This article was originally published in the November/December print issue of Art Guide Australia.