Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

Dan Withey first saw Reg Mombassa’s paintings as a child growing up in Birmingham, England, a world away from the iconic Australian scenes Mombassa is known for. They inspired Withey deeply and went on to play an instrumental role in his development as an artist. Now based in Adelaide, Withey creates paintings recalling Mombassa’s brightly graphic aesthetic with a focus on pop culture, environmental issues and globalisation.

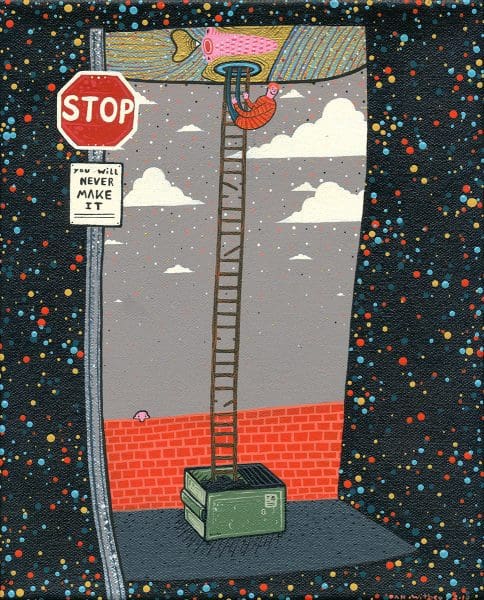

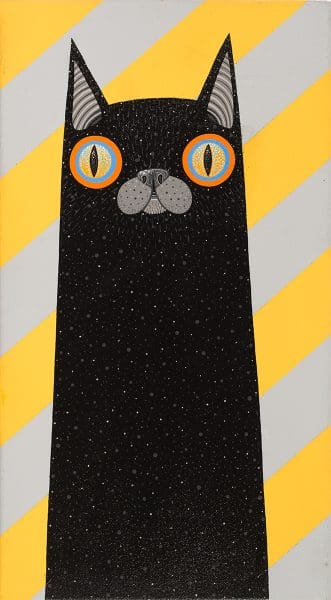

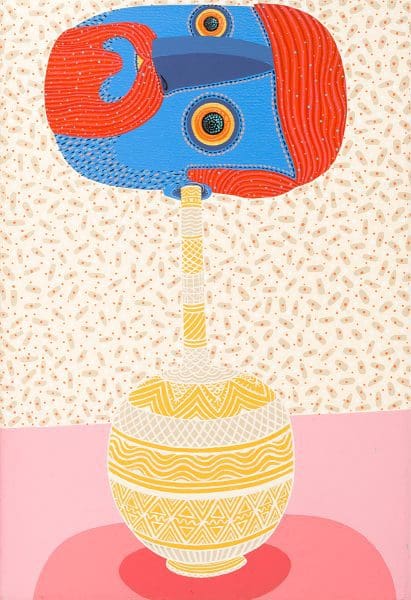

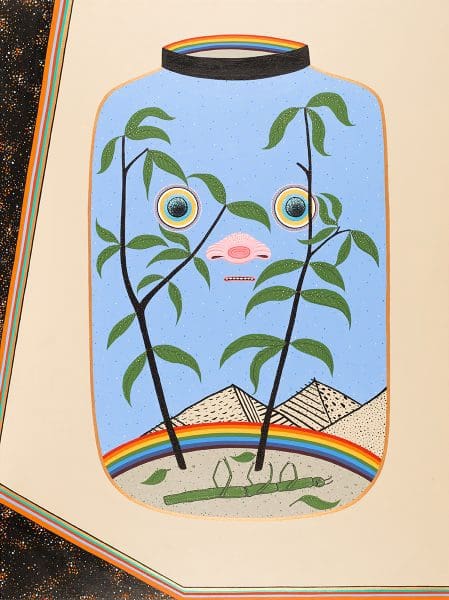

Consumerism and freedom are also explored in Withey’s images and his exhibition Bits of Forever, at Penny Contemporary in Hobart, reads like diary pages for the Anthropocene. While Withey initially appears to follow Mombassa’s style, in this body of work he has moved away from Mombassa’s Australiana to follow a more semi-autobiographical thread.

In Bits of Forever, Withey’s paintings are snapshots into a strange world of giant red-haired men, black cats and daydreaming birds. Repeating patterns, colours and textures evoke meaning and invite the eye to linger over each image. Working with bright acrylics, in paintings like Strange avatars we inhabit, every inch of the painted surface is covered by colour and detail. A standout painting is If you can only hear it is it real. Here a man dressed in stripes rests beneath a vast landscape, his ear sticking through the surface of the dirt as though it is a lake. We wonder what he can hear with one ear above the ground and the other below.

Withey’s forms are solid, his line work bold and shapes clearly defined. Even though Withey’s images are densely populated, there is a sense of order and sharpness. At times they are reminiscent of the work of Sydney-based artist and graphic novelist Pat Grant and American illustrator Gary Baseman. Several large paintings appear in Bits of Forever yet the majority of pieces are compact A4-sized works. While Withey’s illustrative style suits a larger format, the smaller paintings add to the storytelling nature of the exhibition and make it seem like Withey is slowly revealing a secret.

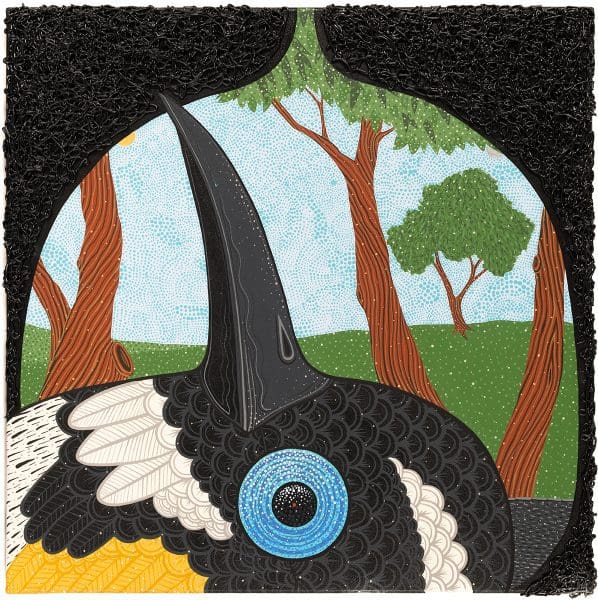

The Last Day of the Honeyeater is another highlight. In the foreground is a close-up of a bird with shiny feathers of black, white and yellow. Its blue speckled eye is the focus of the composition and the bird lies with its head turned to the sky, presumably close to death or already departed. The bird is positioned against a background of sinuous trees and textured blue sky. It is a striking yet melancholic image. This sense of melancholy persists throughout Withey’s work and behind the colourful façade of Bits of Forever there remains hints of doubt, mortality and environmental decay.

Whether scattered across the surface to create a galaxy of rainbow hues or a backdrop of swirling mitochondria, this technique lends an appealing depth and texture to Withey’s images. Unlike the fine, analytical dots of pointillist pioneer Georges Seurat, Withey’s technique is loose and fluid, more akin to illustration and the Ben Day dot printing process commonly seen in vintage comic books.

His background includes a Bachelor of Visual Communication majoring in illustration from the University of South Australia and these skills are clearly evident in his oeuvre. As a self-confessed thinker, Withey’s filled-to-the-brim surfaces reflect a rapid outpouring of thought. Like Mombassa, Withey retains an accessible individualistic style that straddles the divide between pop culture and fine art, offering the viewer an engagingly alternative view of modern life.

Bits of Forever

Dan Withey

Penny Contemporary

16 March – 10 April