Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

Dale Harding working on his commission onsite at the Queensland Art Gallery. Photographs: Chloe Callistemon © QAGOMA.

Dale Harding working on his commission onsite at the Queensland Art Gallery. Photographs: Chloe Callistemon © QAGOMA.

Dale Harding working on his commission onsite at the Queensland Art Gallery. Photographs: Chloe Callistemon © QAGOMA.

Dale Harding, Body of Objects, front cover.

Dale Harding’s studio, 25 January 2017. Photographer: Carl Warner.

Dale Harding graduated from the Queensland College of Art in 2014, yet his opportunities and achievements since speak to a much longer practice, indeed a “cultural continuum” to which he is connected through country. His artwork includes wall murals, sculpture and installations which are an exploration of the political histories and presence of his family and his Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples and their network of cultural sites spread across the central Queensland sandstone belt.

This year, aged 35, he has been included in documenta 14, the 11th Gwangju Biennale, Defying Empire at the National Gallery of Australia and The National in Sydney. The first book on his work, Dale Harding: Body of Objects was published by Griffith University, and a wall painting by Harding is an integral part of the conceptual rethink of the Queensland Art Gallery Australian art permanent display, launched in September 2017. Some of the works Harding has produced this year are collaborations between Harding and his family, particularly mother Kate Harding, uncle Milton Lawton, and cousin Will Lawton. Louise Martin-Chew met with Dale Harding and found out what he gained from this incredible year and what he plans to do next.

Louise Martin-Chew: Your work has attracted attention since very early in your artistic career. Yet you didn’t start studying art until you were in your early thirties. What did you do prior?

Dale Harding: I had great advice from a couple of teachers at school, which was to get your 20s out of your system and then go to art college. I was quite conscious of that and I kept my hands and mind busy, working in the paint industry with commercial house paint sellers, and making art at night.

LMC: Your family connections to country are strong and you view your work as an artist and researcher as an extension of this cultural continuum. How is this made manifest in your practice?

DH: I gathered the language and concept of cultural continuum from fellow artist Warraba Weatherall and his family, and their discussions around cultural practice and repatriation. It has allowed me to frame what I do as one stream in my family’s continuation of cultural practice.

LMC: Where do you hope this direction will take you?

DH: We are maintaining a sense of who we are in ourselves and growing that in each other and particularly in the young people who are around. Times are constantly shifting in the way in which we are seen as a family and cultural unit as Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal peoples and in the larger network as a community.

LMC: Your country includes Carnarvon Gorge, and a large area of cultural sites in central Queensland, with a legacy of some 20,000 years of Indigenous occupation. Is that daunting?

DH: It is daunting in the sense of approaching it with a very profound respect, reverence and care. Sometimes that respect, reverence and care, and wanting to do the right thing, has petrified my hand. But it is not daunting in the sense of claiming culture. I do that now so as not to undermine or diminish or trade on the cultural practice as practiced by previous generations, and how we do it now for ourselves and continue what they have given us as well.

LMC: This year you have had incredible opportunities both national and international. Yet it is only four years since you graduated. How does the academic process impact your work?

DH: I’ve been conscious for some time of senior practitioners like Judy Watson, Julie Gough and Fiona Foley. These artists have led research-based arts practices around an artwork, and bringing that to life has been influential. The academic framework supports that and a depth of enquiry that I really enjoy.

LMC: Your wall painting/installation for the Queensland Art Gallery will be part of the new hang of the Australian collection. What shaped your decisions about this work?

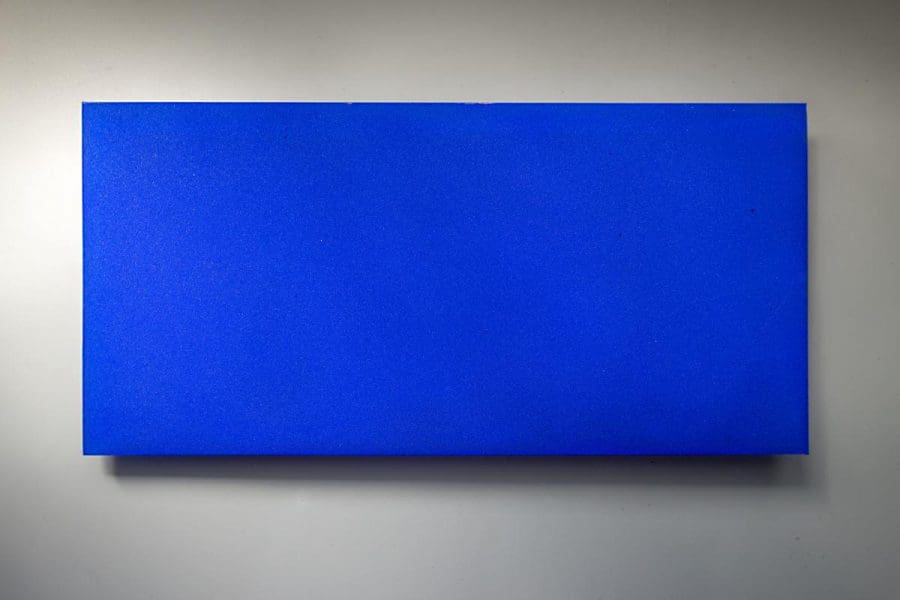

DH: I’ve been sharing with curator Bruce McLean, who is from the Wierdi people of the Birri Gubba nation of Wribpid in central Queensland, around material choices. The use of Reckitt’s Blue in this wall painting springs from some of our discussions. Reckitt’s Blue is antiquated and known for being a laundry whitener. It has many different histories, including its introduction to Indigenous painting in the Carnarvon palette in the mid 19th century, and it remains visible on historic clubs and shields. I have used it sprayed on the wall to form a composition that is referencing, more than imitating or copying, the lineage of a long landscape format along a plaster board wall at the Queensland Art Gallery.

LMC: It includes motifs that are different to the traditional Aboriginal objects (boomerangs, woomera, spears and shields) in your previous work. What informed it?

DH: In many ways it is a notional shift in the way I was working, although with each work my family could speak about its intent in five different ways on five different days. It is the same with the Queensland Art Gallery painting. The water story of Carnarvon tells that the rain that falls from there ends up ultimately in Brisbane’s Moreton Bay. The painting speaks of abstraction and registers of the body over generations, using my body. Warraba Weatherall has lent his support in the making of this work and it is a register of our two bodies on the wall in that space. The imagery is a move away from material culture. This time, I have used a shovel from the Taubmans paint factory.

LMC: What influenced your new works in your solo show, To cast a bright shadow, at Milani Gallery?

DH: Every one of the wall paintings I have done has been a study in learning my contemporary practice in a gallery context. The 11th Gwangju Biennale wall work was in stencilled natural ochres using a figure and other marks, and I realised monochrome had to come next in my colour palette. I thought I could just use depiction without figuration and I began looking at colour field painting.

LMC: This has been an incredible year for you, with many opportunities. Can you identify highlights?

DH: I don’t know where to start, documenta was incredibly rewarding, enriching and inspiring. It was humbling to share that with other Australian artists Gordon Hookey and Bonita Ely, who have their own histories. This is where the works for Milani become small distilled lessons to the future in my practice, to remind me of what I have garnered and am looking for in the future.

LMC: Griffith University Art Museum director Angela Goddard described you as “the man of the moment.” What will be next?

DH: This year has been a year of discussion, discussion shared with curators and artistic directors and other artists. I start to see the beauty of the year in the genuine discussions and generosity shared with me. I can’t frame it well enough. If there had been a fire in the middle of the space in which we were sitting, there could have been no less warmth.

To cast a bright shadow

Dale Harding

Milani Gallery

30 September – 24 October