Reframing a Collection

Drawn from the Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art at the University of Western Australia (UWA), Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery’s show Place Makers, reframes the artists—who just happen to be female.

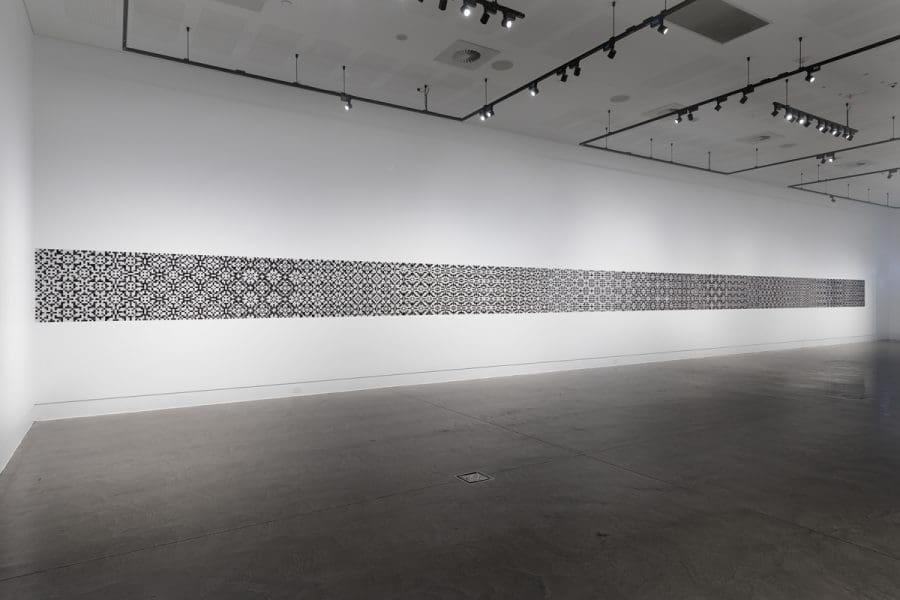

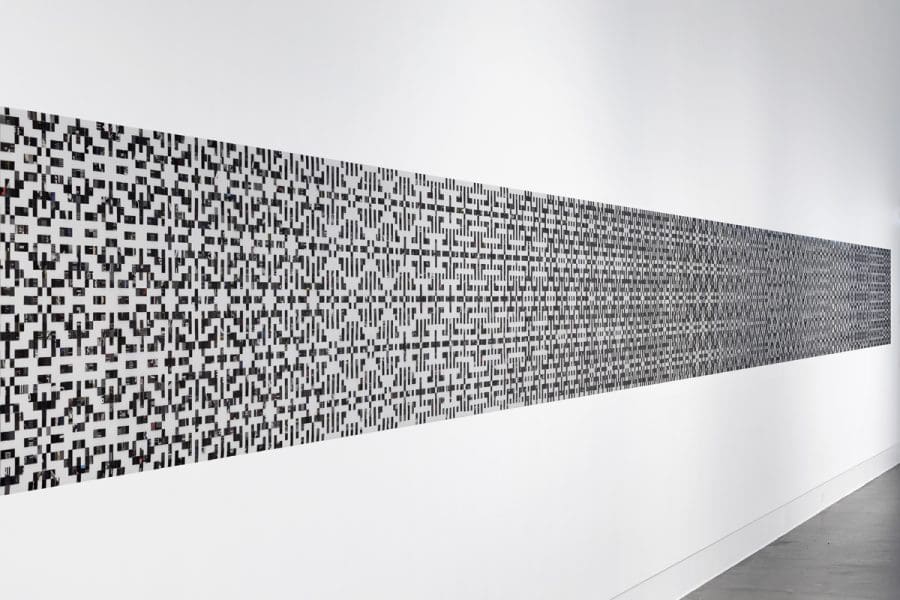

Elizabeth Gower, Monochrome Compilation (installation view, Cuttings, Geelong Gallery, 2018) 2018, paper on drafting film. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne. Photographer: Andrew Curtis.

Elizabeth Gower, Monochrome Compilation (installation view, Cuttings, Geelong Gallery, 2018) 2018, paper on drafting film. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne. Photographer: Andrew Curtis.

Elizabeth Gower, Monochrome Compilation (installation view, Cuttings, Geelong Gallery, 2018) 2018, paper on drafting film. Courtesy of the artist and Sutton Gallery, Melbourne. Photographer: Andrew Curtis.

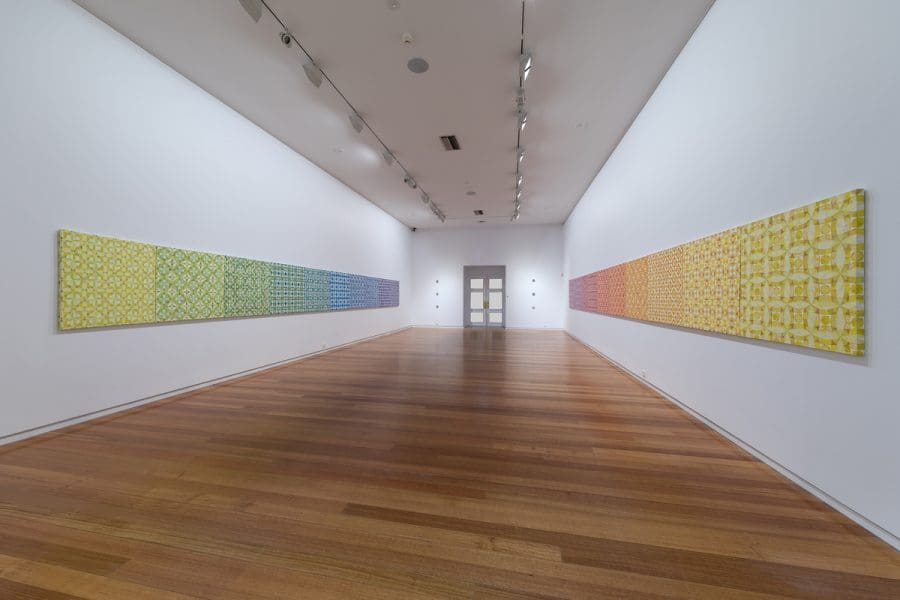

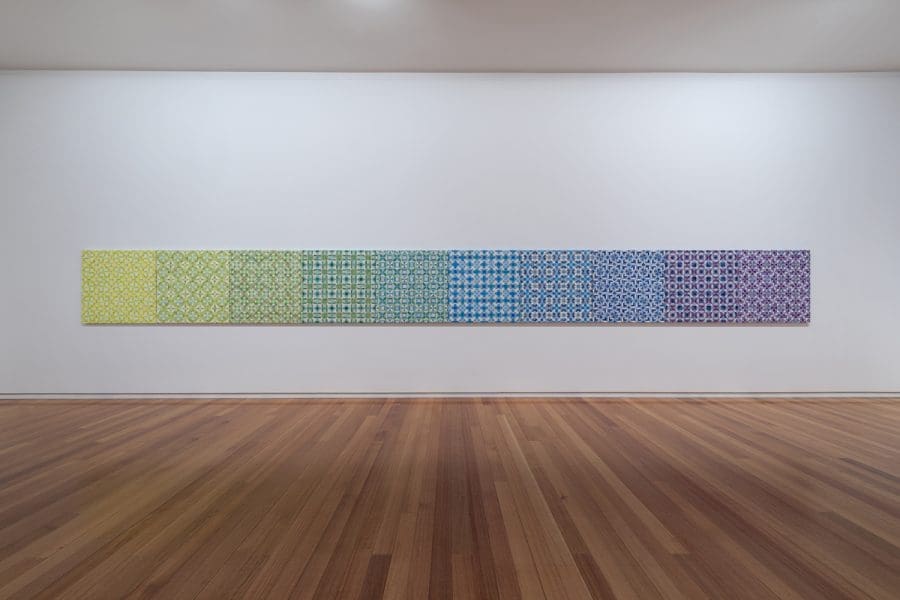

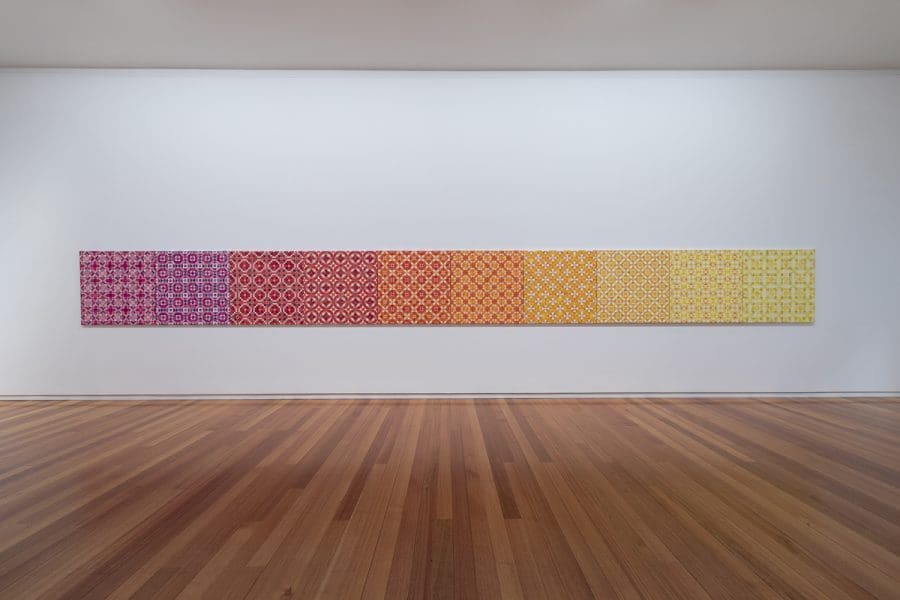

Elizabeth Gower, Prismatics (installation view, Cuttings, Geelong Gallery, 2018) 2006–07, paper on canvas. Courtesy of the artist, Sutton Gallery, Melbourne, and Milani Gallery, Brisbane. Photographer: Andrew Curtis.

Elizabeth Gower, Prismatics (installation view, Cuttings, Geelong Gallery, 2018) 2006–07, paper on canvas. Courtesy of the artist, Sutton Gallery, Melbourne, and Milani Gallery, Brisbane. Photographer: Andrew Curtis.

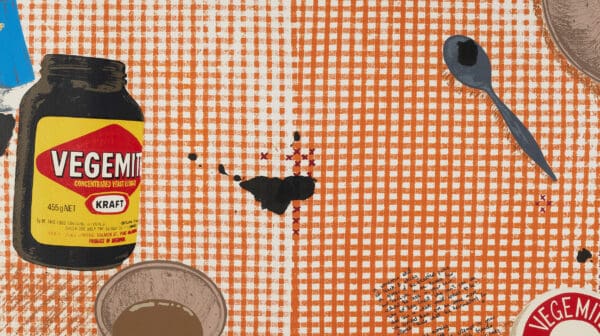

In Cuttings–Elizabeth Gower, visitors to Geelong Gallery can see a 21-metre-long artwork hand-collaged from paper scraps just two centimetres square. Gower’s epic composition, Monochrome Compilation, 2018, is one of eight bodies of work in this major survey show. The exhibition showcases the Melbourne-based artist’s longstanding core practice of collecting, ordering, and collaging informed by pattern as language. Made from printed ephemera such as packaging and advertising material, Gower’s collages transcend their mundane origins through a sophisticated synthesis of pattern, colour and tone.

Eclectic references such as knitting and embroidery patterns, crossword puzzles, QR codes, and LED news tickers are synthesised into abstract works that speak to the history of pattern as encoding, and abstraction as a form of language. “Knitting and embroidery patterns were invented a long time before computers, so the whole notion of creating an image or design using pixels comes from there,” says Gower. The artist values patterning history and sees it running concurrent with art history’s more conventional focus on figuration.

“You can trace cultural shifts through people using the same patterning, how they take on different meanings. You can tell the difference between an art nouveau pattern and a pop art pattern. A Moorish design is different to a paisley design. There’s a whole language there that’s quite abstract,” she says. Gower’s collage patterns derive from another collection habit: an accumulation of photographs she has taken of patterns on walls, floors and other sites worldwide.

Gower periodically returns to making monochrome work. “I think I exhaust myself with colour sometimes and tend to flip from one to the other,” she explains. The dense manipulation of colour in Prismatics, 2006-2007, which goes through all the prismatic steps within its 20-metre length, and the super-fine shreds of coloured paper in Delineations, 2017, are likely to support this theory of the artist’s occasional chromatic enervation.

Given infinite sourcing possibilities online, however, Gower instead recognises the value of setting boundaries. “When I was cutting out imagery, people would say, ‘Why don’t you just download it off the internet?’ But I like to find it,” she says. “There’s a limitation to only finding this many objects or only finding this colour. I like that challenge. On the internet I could get whatever I wanted, so there’s not so much of the thrill of the catch.”

Gower’s analogue, collection-based technique also gives her work the surprise of a distinctly handcrafted presence at close viewing compared with its more seamless graphic quality when seen at a distance. Since Geelong Gallery is showing Gower’s work with no glass or other barrier between works and viewer, visitors will be readily able to access these two registers for a visual experience that is at once spatially bold and extraordinarily detailed.

Cuttings–Elizabeth Gower

Geelong Gallery

1 September – 25 November