The Cruthers Collection of Women’s Art at The University of Western Australia lays claim to being the largest specialist collection of its kind in Australia. In the group exhibition Matter, curator Lee Kinsella mined this diverse body of work for pieces that have both metaphorical and physical weight. Kinsella spoke with Tracey Clement about traditional notions of women’s work, discovering a kind of transformative material alchemy in certain artworks, and the community engagement that has shaped many of the artists she selected for Matter.

Tracey Clement: Materiality, of textiles for example, has been central to some forms of women’s work. Do you think this traditional connection has shaped the practices of the women in Matter?

Lee Kinsella: Definitely, although it’s probably more obvious in the case of textile practices because there is that legacy of women working in a creative community, sharing designs and supporting each other in the making of collaborative pieces.

In September, we will be showing a fantastic piece by Rhonda and Susannah Hamlyn, a mother and daughter who would stitch pieces together. It’s called Chit Chat, 1996, and it links to the Second World War material in the show and to the history of ‘stitch and bitch’ sessions where women would gather, knitting socks and undertaking other kinds of Homefront activities; working in the community to provide support for the soldiers, but also support for each other in the making of something for the war effort.

I think the Hamlyn piece emerges from that same making process and the collegiality of makers working together and sharing and supporting each other– in their creative practices, but also in their lives more generally as well.

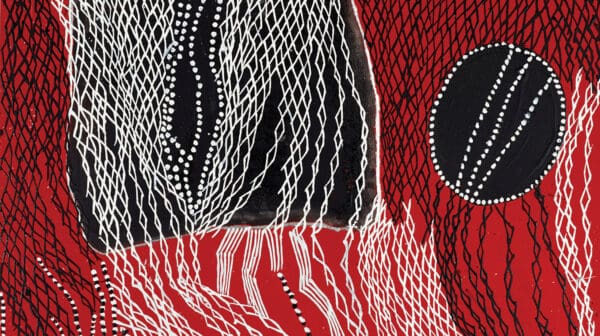

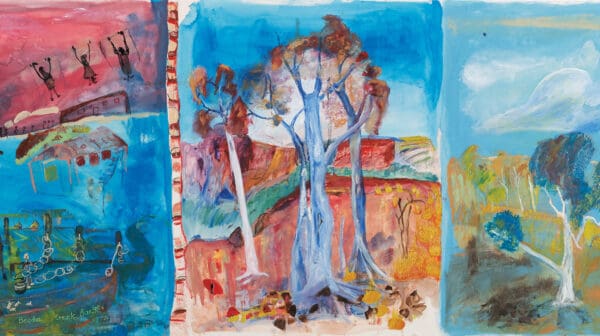

Another very clear example is the collaborative work from the Hermannsburg Potters, Pink galahs in flight around Ntaria, 1995. It is a beautiful, large ceramic mosaic on which Maggie Watson, Carol Rontji, Elaine Namatjira, Dulcie Enalanga, Beryl Entata, Irene Entata, Noreen Hudson, Elizabeth Moketarinja and Virginia Rontji seamlessly worked together to create a unified landscape that is three-dimensional and just lush in its rendering. It has a visual connection to the watercolours of Albert Namatjira and to Country and to embedded knowledges and cultural understandings of place.

TC: The show seems to contain a really disparate range of artists and works across a wide span of time…

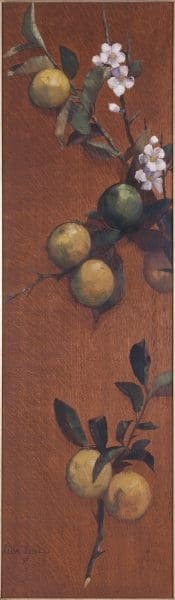

LK: It spans a massive historical period! We are showing a very beautiful 1896 cedar wood panel painting by Lilla Lowe, Apples and apple blossoms, alongside contemporary artworks like Lisa Wolfgramm’s abstract Painting #271 from 2009.

It is a diverse survey, and it comes from a collection that is incredibly diverse in its range as well. And to be honest, I think that’s probably one of the strengths of the collection: there is never a sense of it being a completely coherent running chronology or being tied to a distinct canon per se.

TC: You’ve already mentioned a couple of pieces. Are there any others that really sum up the theme of Matter for you?

LK: Well, the crux of the concept was artists’ manipulation of materials to a particular end: they have something in mind, conceptually, that they want to investigate through matter. So Wolfgramm is a good example. She diluted acrylic paints and then syringed them at the top of her canvas and manipulated it as the paint ran down. She then left the pigments to dry and, as a result, the painting has a beautiful lower edge of dried paint drops. So, for me, this is a key piece in terms of capturing the transformation of materials to achieve a particular end point, and in such a way that the process was revealed too.

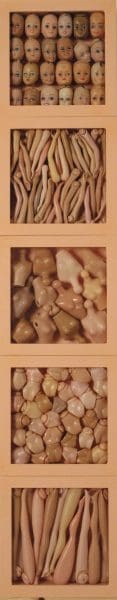

And I think that’s also true of Michelle Nikou’s bronze tissue boxes. In Untitled, 2001, the casting process is reflected in the plaster skin that remains, a kind of powdery surface. They represent something of the alchemy by which artists are able to communicate their thoughts in tangible form.

As I’ve said, the collection is really diverse, so there are so many ways to engage with it. In this instance, I was making a connection on the basis of textured and gritty surfaces, but also metaphorically in terms of subject matter of weight and significance.

TC: Let’s go back to the collection. The Cruthers gift had at its heart portraiture and self-portraiture by women. It can be argued that all artworks are self-portraits of their makers. In this way, can the collection be read as a kind of portrait of the changing face of women in Australia?

LK: I think we’ve got to be really careful that we don’t reduce it to essentialist notions of what women’s work is. Portraits and self-portraits continue to be an interesting way to consider contemporary practice. Collecting portraits is certainly a principle that’s reflected in the University’s acquisition policy and that we continue to pursue.

In Julie Dowling’s portraits of members of her family and of the Stolen Generation that are on display in Matter, she has built up glittery surfaces which speak to the shimmery life of the individuals she paints. And I think that’s absolutely one of the drivers of her practice; bringing Indigenous faces and Indigenous histories into public spaces to have a presence and life of their own.

Like so many of the works in Matter, while they are very physical in their bearing, these objects speak of so much that is intangible.

Matter

Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery

17 July – 27 November