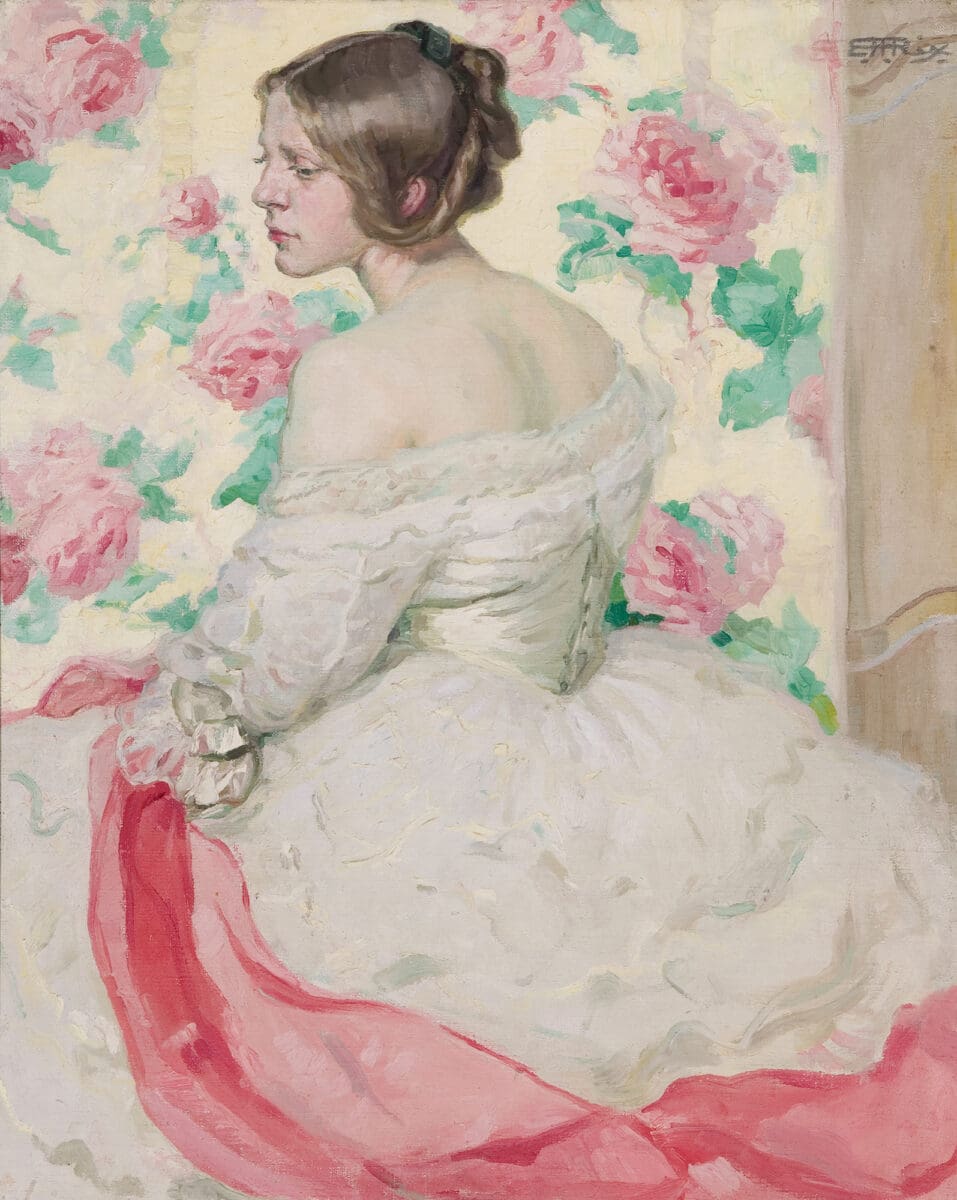

Adelaide-born modernist artist Bessie Davidson built a career in Paris. She wrote home to her father, urging him not to worry, that she had many buyers for her paintings, which were usually of interior furnishings or women she knew well. “I was born under a lucky star,” she reassured him.

The letter’s optimistic twinkle belied the earthy reality for many Australian women artists such as Davidson who travelled to Europe around the early 20th century yet were often “overlooked or misunderstood” at home during their lifetimes and were “certainly obscured in written accounts of art history,” says associate curator Elle Freak of the Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA).

Davidson first travelled to Europe in 1904, at age 25, with her Adelaide-born art teacher and close friend Rose McPherson, later famously known as Margaret Preston, one of Australia’s most significant artists. The pair returned to Australia after two years, with the AGSA first acquiring some of Davidson’s work in 1908.

Davidson then decided to return to Europe and, except for two short visits home, lived in Paris permanently from 1910 until her death in 1965. Her lack of institutional recognition in Australia was due in part to her lack of exhibitions here across that time: “She considered Paris to be her new home, and she was very successful there,” says Freak.

A founding member of the Salon des Tuileries, Davidson’s influence in Paris grew as she became secretary of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, in 1922. France also afforded her a liberal sexual freedom: a female figure glimpsed in the mirror of one of Davidson’s paintings has been identified as Davidson’s wealthy French partner, who upon death left her estate and Paris apartment to Davidson.

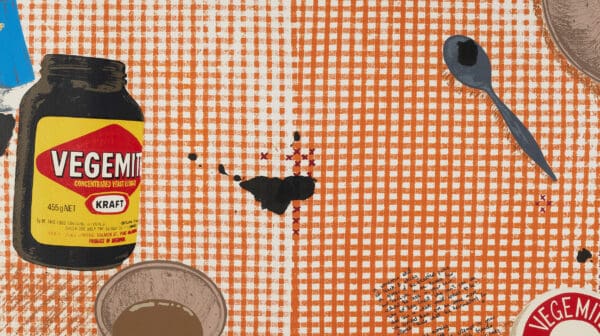

But bias against subjects chosen by women artists of the time—intimate interiors and “very feminine spaces”—helps explain their neglect at the hands of local critics and chroniclers, says Tracey Lock, curator of Australian art at the AGSA. The women’s artistic achievements were “quietly subsumed by the collective war effort,” while male artists were lauded for painting both rugged and bucolic landscapes as part of a nationalist project of what it meant to be Australian.

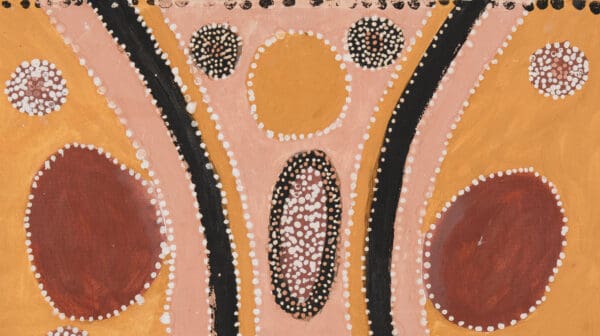

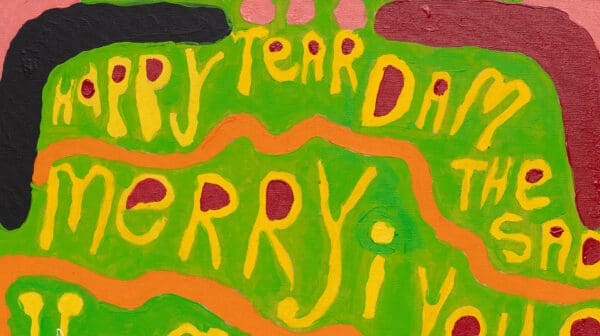

Meanwhile Preston was among the handful of women artists to become well known “because she fed into that whole dialogue of creating a national form of Australian art,” says Lock. As a printmaker, woodblock maker, painter and writer, Preston championed modernist as well as Aboriginal and Asian art. “Don’t forget, she was very ambitious, and she knew a route to success and feedback.”

Bessie Davidson’s story meanwhile has parallels with Victorian-born portrait and interiors artist Agnes Goodsir, who left Australia in 1899, living in Paris until her 1939 death, associating with Gertrude Stein and Pablo Picasso. Several of Goodsir’s paintings featured her partner and muse Rachel Dunn, nicknamed Cherry, such as Girl with Cigarette, circa 1925, and Goodsir exhibited often in Paris. Yet many Australian institutions have yet to acquire her work.

In a new exhibition, Dangerously Modern: Australian Women Artists in Europe 1890–1940,

co-curated by Lock, Freak and Art Gallery of New South Wales head curator of Australian art Wayne Tunnicliffe, 50 Australian women artists will be celebrated, bringing the work of many to light to local audiences while also focusing on lesser-known works of the recognised few. The title “dangerously modern” was applied by a Sydney critic to NSW-born artist Thea Proctor, who had studied in London (her drawings, watercolours and lithographs were comparatively conservative).

“These 50 travelling women we have focused on were in fact incredibly well informed,” says Lock. “Many put themselves in challenging situations at times and made great sacrifices to participate on the international stage.”

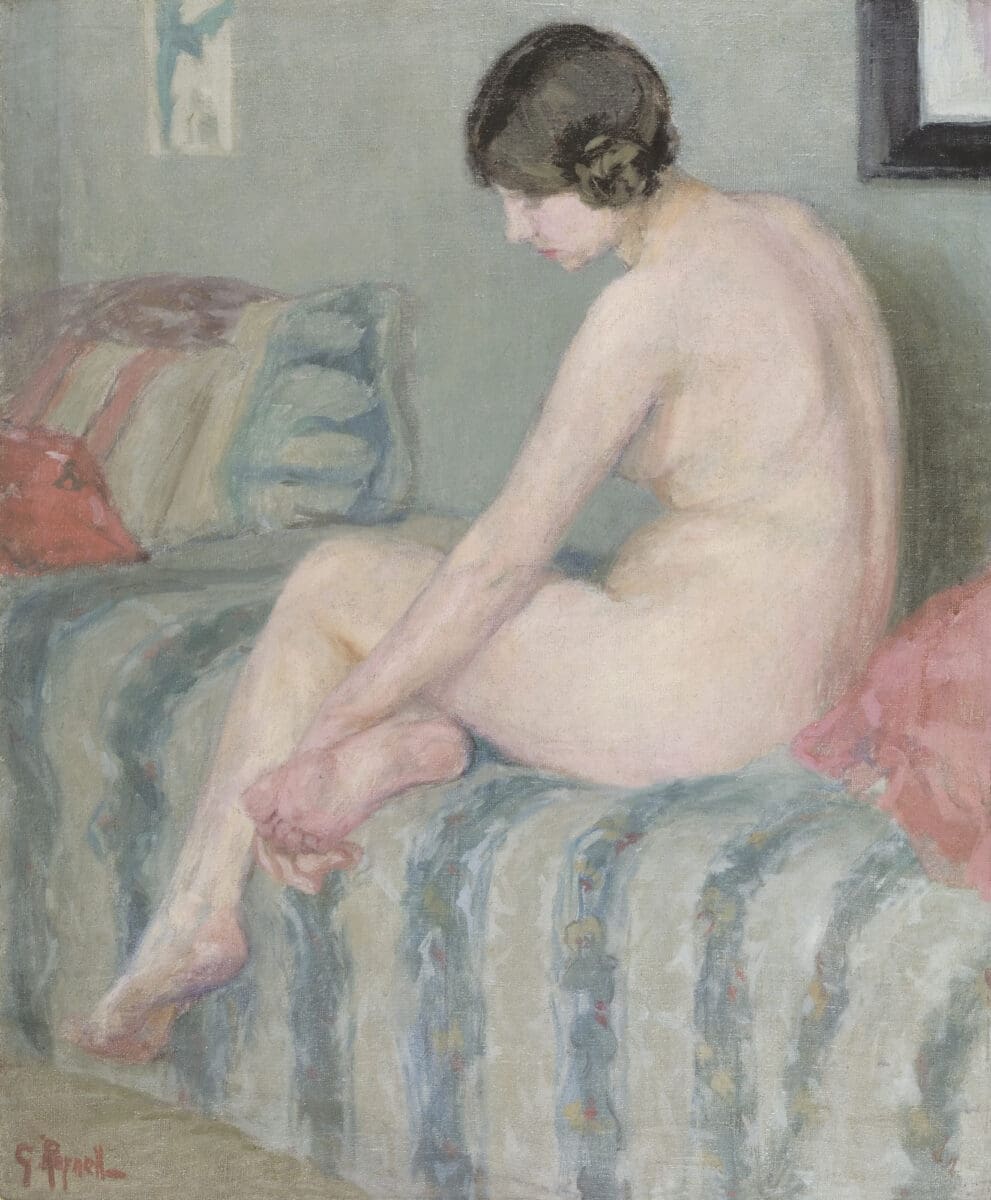

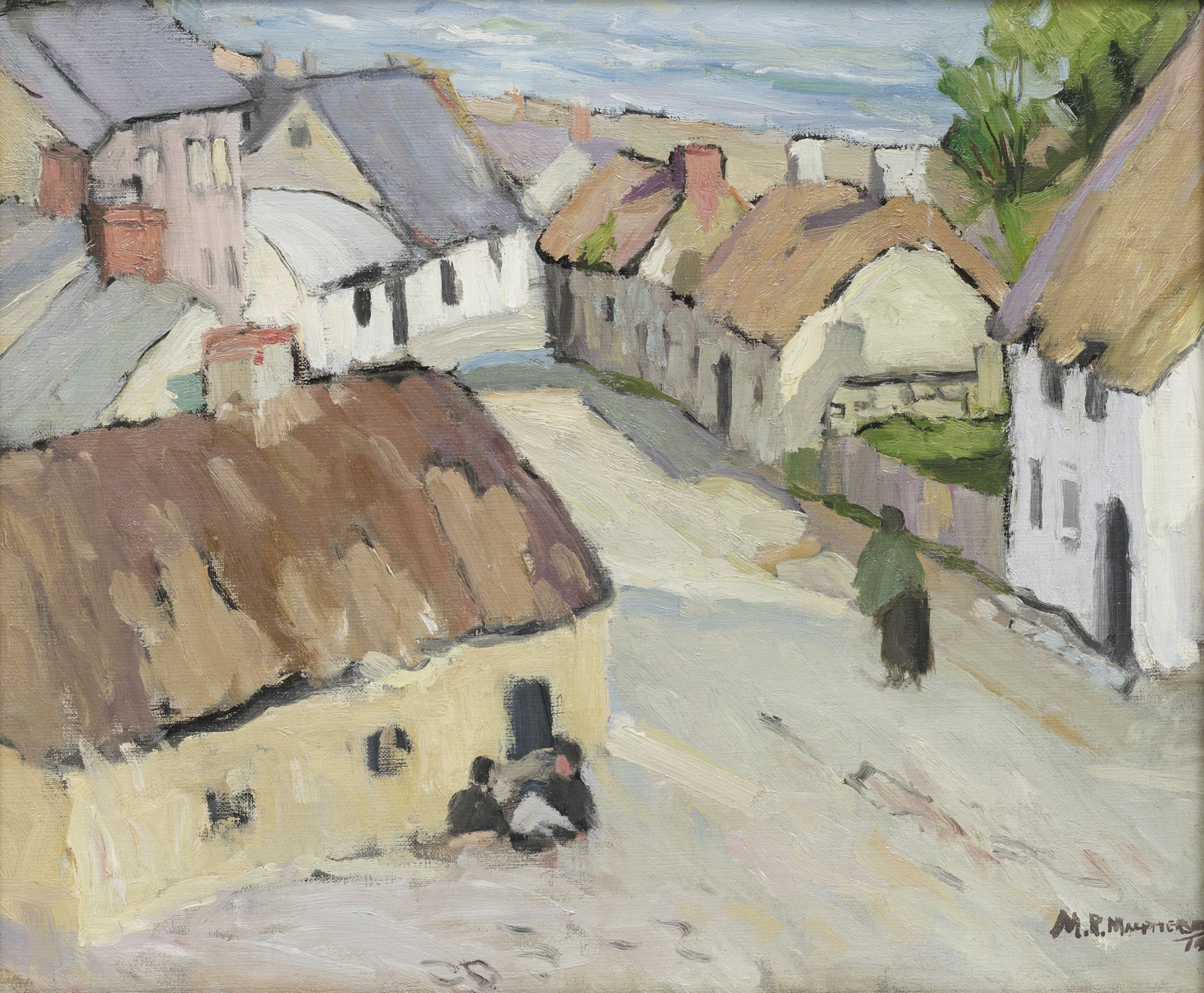

The exhibition will also examine their cultural exchanges: Preston sailed to Europe again in 1912, this time with Adelaide-born modernist potter Gladys Reynell. Preston remained in England until 1919, often painting county villages. In 1914–1915, she taught more than 20 female students at Bunmahon (then Bonmahon) in southern Ireland, imparting modernist values via painting and printmaking.

Meanwhile, an unremarkable trio of Cubist landscapes depicting the Mirmande commune in south-eastern France, each painted by an Australian woman artist in 1928, tells an intriguing bigger tale of artistic influence: Adelaide-born Dorrit Black and New South Wales-born artists Grace Crowley and Anne Dangar studied with French Cubists André Lhote and Albert Gleizes, two male artists who were also great rivals.

Crucially, Black brought Cubist philosophy back to Australia and opened the Modern Art Centre in Sydney in 1931—the first gallery in Australia to devote itself to modernism, underscoring women’s often unsung achievements in the field.

“After [the Australian women] left, their lives were never the same again,” says Lock. “They embarked on seriously professional careers.” Working against the male-dominated odds, journeying from a distant land, they and many of their compatriot women artists are only just now receiving due credit at home.

Dangerously Modern: Australian Women Artists in Europe 1890–1940

Art Gallery of New South Wales

(Sydney/Eora NSW)

11 October 2025—15 February 2026

This article was originally published in the May/June 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.