Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello’s Glass Acts

Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards 2025 finalist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form.

Cressida Campbell, Japanese Hydrangeas, 2005, private collection. © Cressida Campbell.

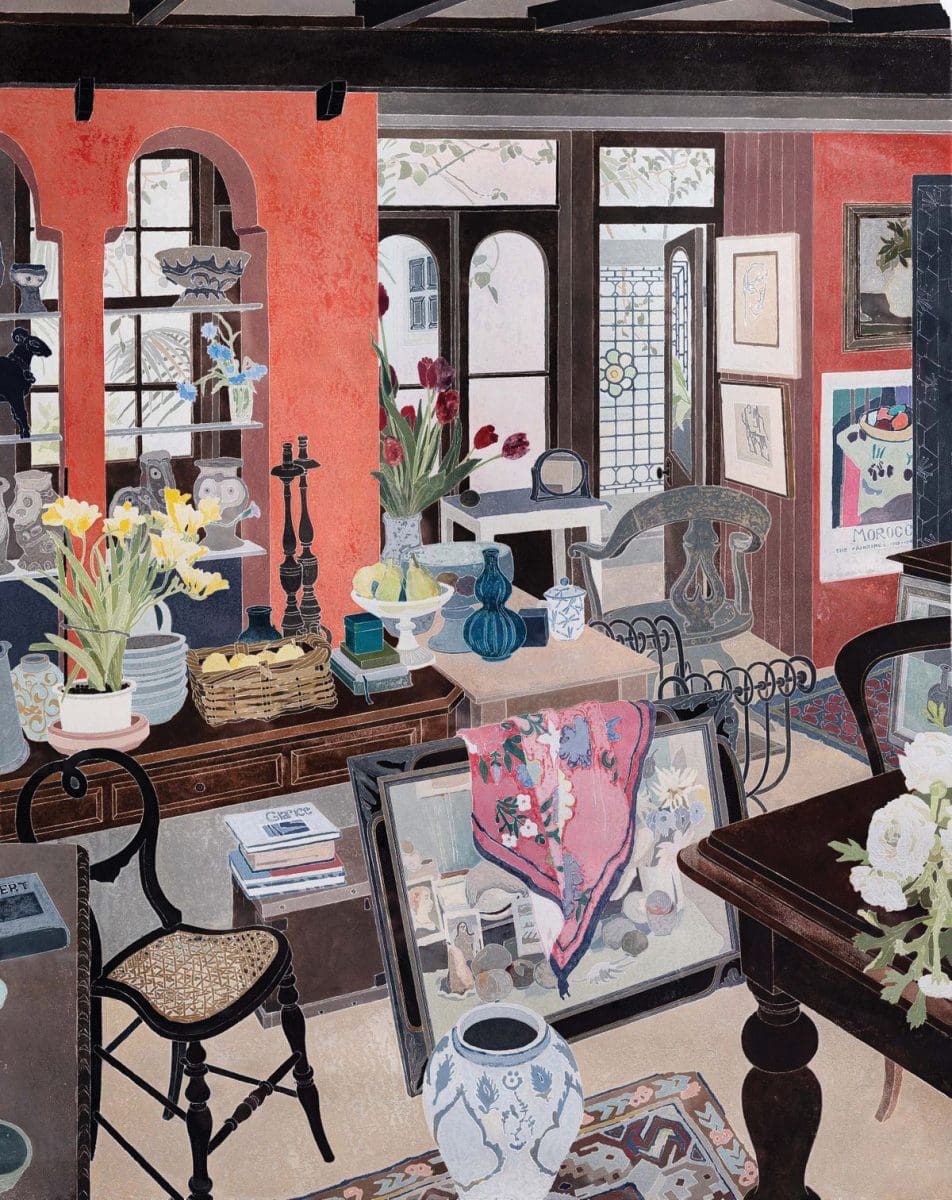

Cressida Campbell, Margaret Olley interior, 1992, private collection. © Cressida Campbell.

Cressida Campbell, Nasturtiums, 2002, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Gift of Margaret Olley 2006, image courtesy the Art Gallery of New South Wales. © Cressida Campbell.

Cressida Campbell, Night interior, 2017, private collection. © Cressida Campbell.

Cressida Campbell, Still life with electric fan, 1997, University Art Collection, Chau Chak Wing Museum, The University of Sydney, donated through The Hon RP Meagher Bequest 2011, image courtesy the University Art Collection, Chau Chak Wing Museum, The University of Sydney. © Cressida Campbell.

Cressida Campbell, Studio, 1989, Mosman Art Collection, image courtesy the artist and Mosman Art Gallery. © Cressida Campbell.

Cressida Campbell, Through the windscreen, 1986, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, purchased 1987. © Cressida Campbell.

Using both painting and printmaking techniques, since the 1970s esteemed artist Cressida Campbell has drawn our attention to the beauty of what is often overlooked: the everyday.

In her final years of high school, and during her time at the East Sydney Technical College in the late 1970s, Cressida Campbell found herself resisting constraints. At the Tech, they wanted students to paint like Cézanne, using big paint brushes. “I was completely not suited to the way they were trying to make me work,” she recalls. “I got self-conscious and was doing these dreadful paintings. They certainly didn’t look like Cézanne’s; it was quite depressing.” She tried printmaking.

Her work today, as she observes, fits neither category, given the uncompromising way it deploys both painting and printmaking skills, with extraordinary effects. Her work is described by the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) as capturing the “overlooked beauty of the everyday”, depicting everything from an unmade bed or a view through a car window, to a cluttered studio setting. All have an intriguing sense of intimacy—evident across more than 40 years, which will be represented in her survey show at NGA.

These days, Campbell remains true to her own methods, even if some people think she is taking the long route via her laborious work with paint, woodblocks, rollers and paper to achieve her idiosyncratic results. “People say, ‘Why why on earth don’t you just paint a picture?’” But the visual design—what she describes as a combination of flat colour and painterly form— relies on techniques from both painting and print. Without this process, the carefully coloured and intricate works would be something else. Little wonder she says her work “never really fitted in anywhere”.

At her Sydney home, she spends much time in the studio and rarely works plein air, as she once did.

It’s not a lack of appetite for the outdoors, but rather a sense of honing in on what surrounds her and the beauty to be found there.

She has recently been creating round pictures of interiors rather than what you’d expect of rooms: oblongs and squares. “It is fascinating. I got into them because I was interested in them compositionally. I love the way straight lines dissect—how straight lines cut the circle. It is often, even though it is naturalistic, very abstract in that it is all about composition and the eye going around and not getting bored. I have found that it gives a strange voyeuristic feel, as if you are looking through a keyhole.”

Campbell owes much to her first explorations with print at the Tech when she became enamoured of the ukiyo-e style of Japanese printmaking. “I love how [ukiyo-e prints] aren’t symmetrical and they are very cropped. It is funny: I have always had that sense of design anyway.” It was fortuitous, then, that in her first printmaking studies, she enjoyed the way she was introduced to techniques rather than subject or style.

“In those days, everyone was doing conceptual art and minimalism and I was wanting to paint and draw whatever I wanted. I did a few etchings and drypoints, but I am not really a black-and-white artist.” She loves colour—although nothing too bright. It is an essential element of what makes her work so distinctly her own.

Her bespoke technique seems complicated, developed when a teacher suggested she draw her designs on plywood and then carve into them, paint them and put them through a press.

This evolved over the years: now, she carves into a woodblock matrix, applies layers of watercolour, and lets it dry. She then sprays it with water and handprints a single impression, using a roller, onto dampened paper. The print is touched up with more paint. The woodblocks can be displayed alongside the print.

The drying of the paint on the block can sometimes take weeks or months, but when it comes time to spray the surface and lay the sponged paper on top, ready for the roller, it is anxiety-inducing, Campbell says. “And, as you can imagine, it is more nerve-wracking the larger the piece. Even now, after doing it for 40 years, it’s an adventure and it’s terrifying. You’d think I would have perfected it by now, but I haven’t.” The main problem is that different coloured paints are absorbed over varying amounts of time. “You can’t stop mid-print and rest at all.”

She has been using the same hand-roller for decades, and she gets just the right amount of pressure as she leans over. “It’s an exhausting process, being constantly worried it’s not going to work.” When the work is printed and dried, she deploys the paint once more, strategically. “I find it satisfying touching them up, it’s like making up someone’s face, gradually this picture appears,” she says.

Preceding the main rooms of the NGA show is a salon hang of juvenilia, reaching back to the zebras she drew as a six-year-old. “My mother kept my childhood drawings and paintings… some are comical and might amuse people. You can tell the strengths and weaknesses from early on, which I always find interesting.”

Cressida Campbell

National Gallery of Australia (Canberra ACT)

24 September—19 February 2023

This article was originally published in the September/October 2022 print edition of Art Guide Australia.