Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

This is a song to halt a storm.

In the Irish Mythology Cycle the figure of Amergin, a druid and bard of the Milesian people, sings an incantation to defeat a magical storm whipped up mid-battle by his rivals. Declaring himself to embody the ocean, the wind, the deer, the sun – essentially, the cosmos – Amergin summons power from Ireland itself and parts the storm, bringing his ship safely to land.

Thousands of years on, for most of us, the weather still represents an unpredictable and inscrutable kind of magic. Our wardrobe choices and gardening plans rely heavily on prophetic interpretations of phenomena (cold fronts, low pressure systems) by the Bureau of Meteorology. And increasingly we’re discovering that the weather is beyond any control: a number of recent United Nations reports suggest that the tipping point for reversing climate change may have already passed. As I write this there are floods in Sydney, fires in Queensland, and it’s only going to get wilder.

Clare Milledge’s new solo exhibition at Station Gallery, Sacks of wind: a rock harder than rock, takes ‘The Song of Amergin’ as its starting point. Milledge’s work has often dealt directly with shamanic traditions and nature-magic. In the time of the Anthropocene this kind of thinking feels increasingly urgent. If there is a way through, it may lie in the acknowledgement that all materials, objects and natural phenomena contain a form of life and agency, what Jane Bennett calls Vibrant Matter. In ‘The Song of Amergin’ the elements of the environment are intimately interconnected, fully alive.

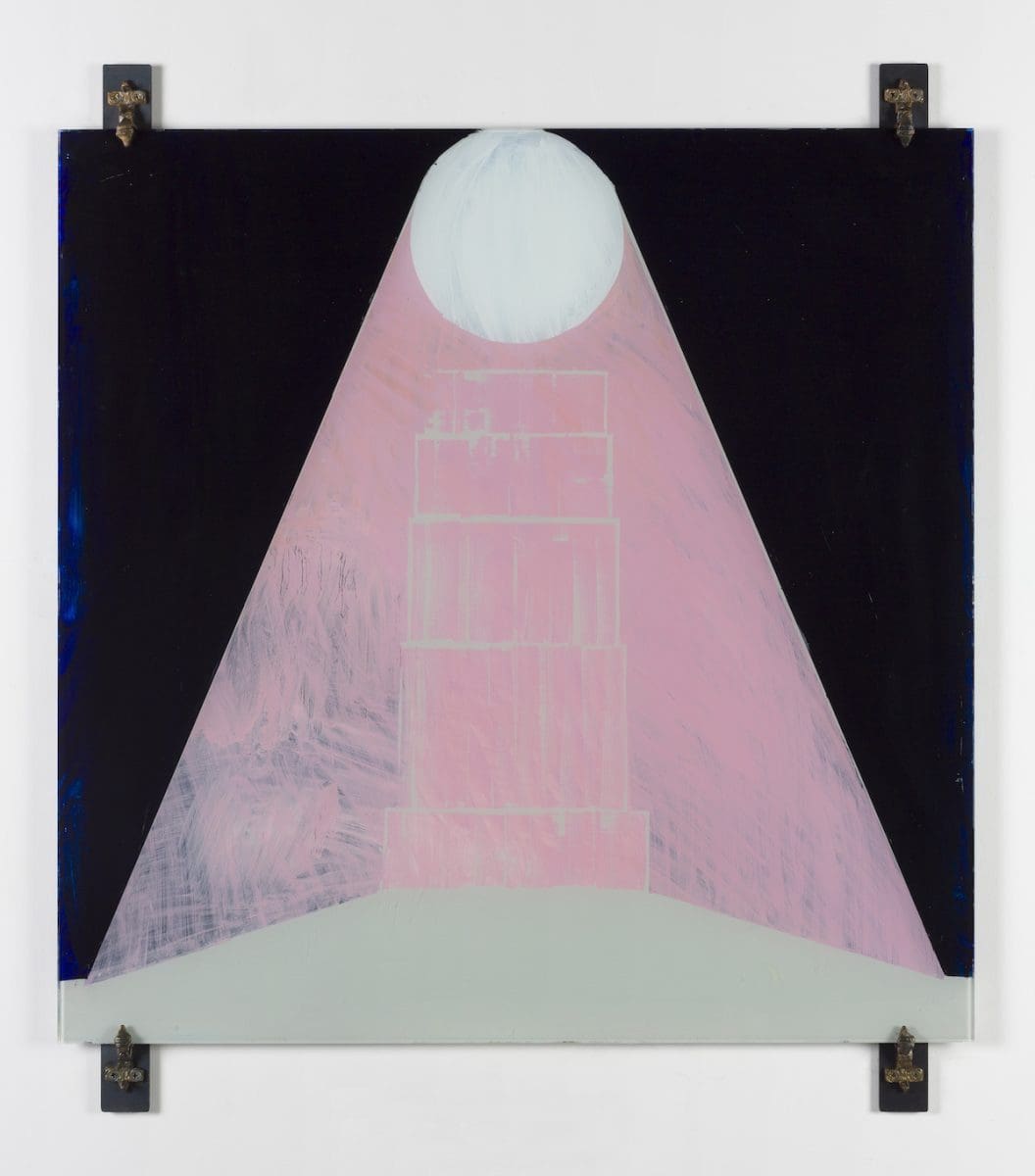

The 11 works in Milledge’s elegant, pared-back installation use the technique of hinterglasmalerei – reverse glass painting – a once-popular folk artform which is a recurring feature in Milledge’s practice. Paint is applied in careful layers to sheets of recycled tempered glass, then viewed from the other side, giving the work an intriguing quality – a flat opacity with an illusion of depth. Loose brush-strokes and scratched lines reveal slivers of colour, ghost images behind the visible paint.

Bronze clasps grip the corners of each unframed sheet of glass. These take abstract animal forms – snakes and insects, hoofs and horns – like small familiars or animal gods. Roughly made and suggestive of ancient rituals, perhaps burial objects, these bronzes the paintings a sense of bodily weight.

Milledge has titled each work with a line of incantation drawn from ‘The White Goddess,’ a 1948 translation by Robert Graves of ‘The Song of Amergin.’ Each statement is bisected with a colon like the two halves of an academic proposition. I am a breaker: threatening doom. I am a hawk: above the cliff. One piece I’m repeatedly drawn back to is called I am a hill: where poets walk: a pearlescent moon casts its light in a translucent rose-pink, thinned so that every brushstroke is visible, against a deep blue.

Milledge’s visual language slips between abstract painting and witchy mysticism; the connections between work and title often oblique. Is gazing at a painting and trying to divine its meaning really so different from reading entrails or casting bones?

In the story of Amergin the supernatural storm is conjured by the original inhabitants of Ireland, that the Milesian people – led by Amergin – are seeking to conquer. Like Amergin, the wild weather we’re experiencing is pretty much our own fault; but as for the song that will reconnect us with nature and quell the storm, we seem to have forgotten the words. Clare Milledge’s Sack of wind: a rock harder than rock is an incantation that reaches towards this lost magic, thrumming in the white-walled gallery and echoing long after.

Sacks of wind: a rock harder than rock

Clare Milledge

STATION

24 November – 22 December