Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

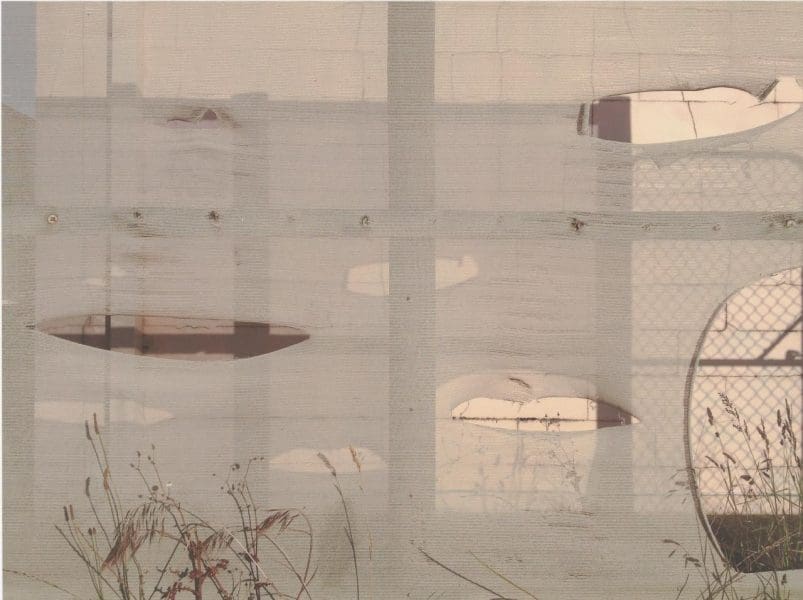

The ambitious and sprawling photography exhibition Civilization: The Way We Live Now opens with five photographs from Steven Rhall’s Kulin Project from 2012–2013. This series explores narratives and relations to land and perceptions of Aboriginal culture. Rhall’s photographs, simply pinned to the wall, showcase seemingly nondescript scenes: a car park, an expanse of ocean, a graffitied wall. But within these images are places of significance to the local Indigenous peoples of the Kulin nation, and to Rhall, who is a Taungurung man himself. It would have been remiss not to open the Australian version of this touring exhibition with the work of a First Nations artist.

A collaboration between the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography in the US and the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Korea, Civilization was exhibited in Seoul and Beijing prior to coming to Melbourne at The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia. And it will travel to Auckland in 2020 and Marseille in 2021. In addition to Rhall, the current iteration of the exhibition includes work by renowned Australian photographers Charles Green and Lyndell Brown, Rosemary Laing, and more.

The end of Civilization features two photographs by German photographer Michael Najjar, one of which depicts a rocket launching into space. It elcits the thought that now that we as a civilisation have used up all our resources, we’re searching for somewhere else to go.

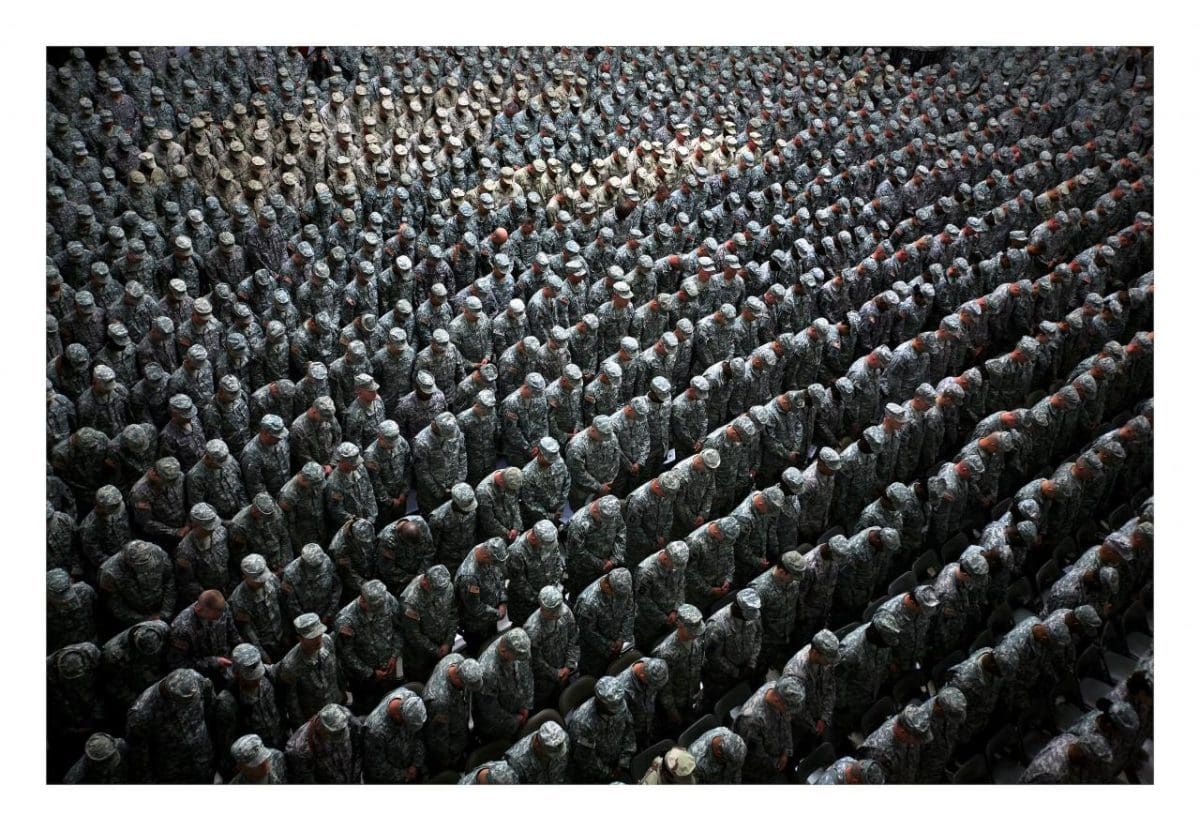

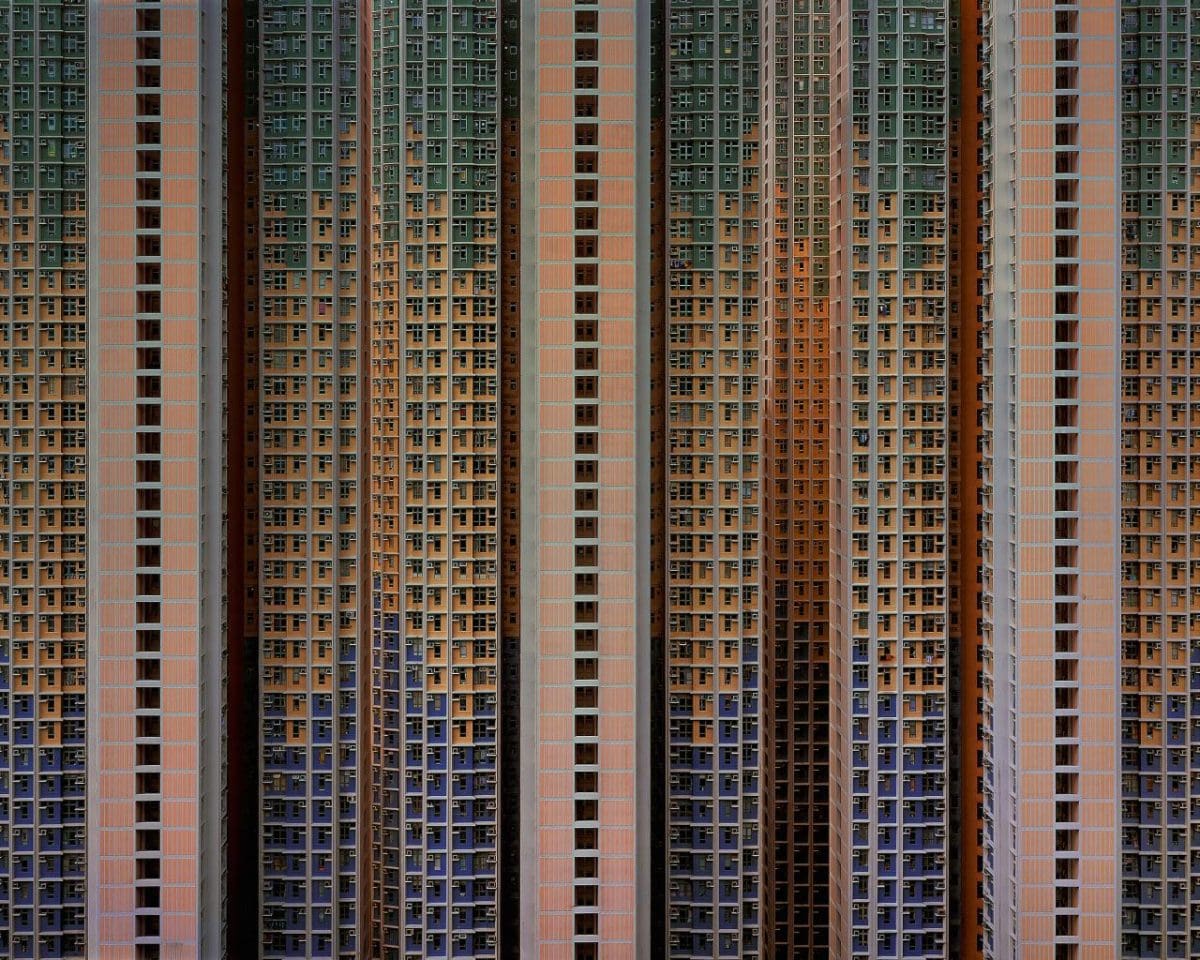

But before we can get to that point there is everything in between to consider: a very wide-ranging summation of the way we live, why we live the way we do and where we do, and more, categorised into eight broad, open-ended themes that refer to the basic characteristics that define a civilisation: hive, alone together, flow, persuasion, control, rupture and escape, and finally, next.

This is not an exhibition to digest quickly or casually. Firstly because there are over 200 works by 100 international photographers, and most of the photographs are large. But mostly because the photographs pose big questions, although admittedly not always in the most nuanced ways. This is most apparent in the ‘persuasion’ category, which gives too much real estate to photographs of advertising and billboards around the world. But then again, it’s hard to be subtle when tackling big question such as: Why do we go to war? What do we believe in? Where does our food come from? Does our government help us? Where do we go from here? Are we in trouble?

For all its grandiosity, what really shines in Civilization is not the theatrics of aerial imagery, the bustling cityscapes or even the mesmerising images of bodies en masse. Instead, it is the quieter images that really speak to our shared existence, particularly those concerning relationships and how we connect with each other.

Anthropology is what lies at the heart of this exhibition, and Dona Schwartz’s Expecting Parents and Empty Nesters series, which fall under the exhibition’s ‘alone together’ category, show the two ends of parenthood and family life. In the former, couples are photographed in the nurseries created for their child. In the latter, parents are photographed in the bedrooms long outgrown by their children.

South African photographer Pieter Hugo’s portraits from There’s a Place in Hell for Me and My Friends are a result of him not “fitting in to the social topography” of Africa as a “white African.” These stark portraits have been colour manipulated to present “colourless” (read: race-less) portraits that go beyond simple notions of black and white.

Two portraits by Alejandro Cartagena – Daughter at the USA-Mexico border wall and Mother at the Mexico-USA border wall, both from 2017 – hang next to Rosemary Laing’s welcome to Australia, 2004, which depicts the former Woomera Immigration Reception and Processing Centre in South Australia.

But it’s not all heartache here. There are moments of happiness and hope in the mix, too. There are many strands of thought underpinning this sprawling exhibition, and to be honest, it’s best if you spend your time in Civilization focusing on the photographs and coming to your own conclusions – or, as is more likely, more questions – about what’s to come.

Civilization: The Way We Live Now

National Gallery of Victoria – The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

13 September – 2 February 2020