Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

In a recent Cordite Poetry Review interview, visual artist Chunxiao Qu, when discussing what exactly constitutes poetry, speaks of a desire for the direct interrogation of her work: “I wish someone would say to me: ‘You think this is poetry? Fuck you!’” And so, when I spoke with Qu, I told her exactly that. She responded with much glee: “I enjoy imagining people who hate my poetry being brave enough to let me know they do, and the same goes for my art.”

Brash as it may sound to some, this is how Qu operates. It was only through moving to Melbourne to undergo further studies in fine art, that she continued to discover the possibilities of art making. Before this, growing up in the city of Qingdao in China, she had a deep interest in art; her parents encouraged her to try as many mediums as she could, such as piano and dance. But she found herself drawn to illustration and painting, saying, “Because art is different, even if it is exam-oriented, you still create your own work, your own colour, your own angle—it definitely has more freedom than other majors.”

Despite this, the art lessons at Kunming University bored her, resulting in a decision to move further afield. In 2016, her first year at Melbourne’s Monash University, she discovered conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth, whose 1965 installation, one and three chairs, left a profound impression. The work represents one chair as an object, image and dictionary definition: it led Qu to explore text as an art form.

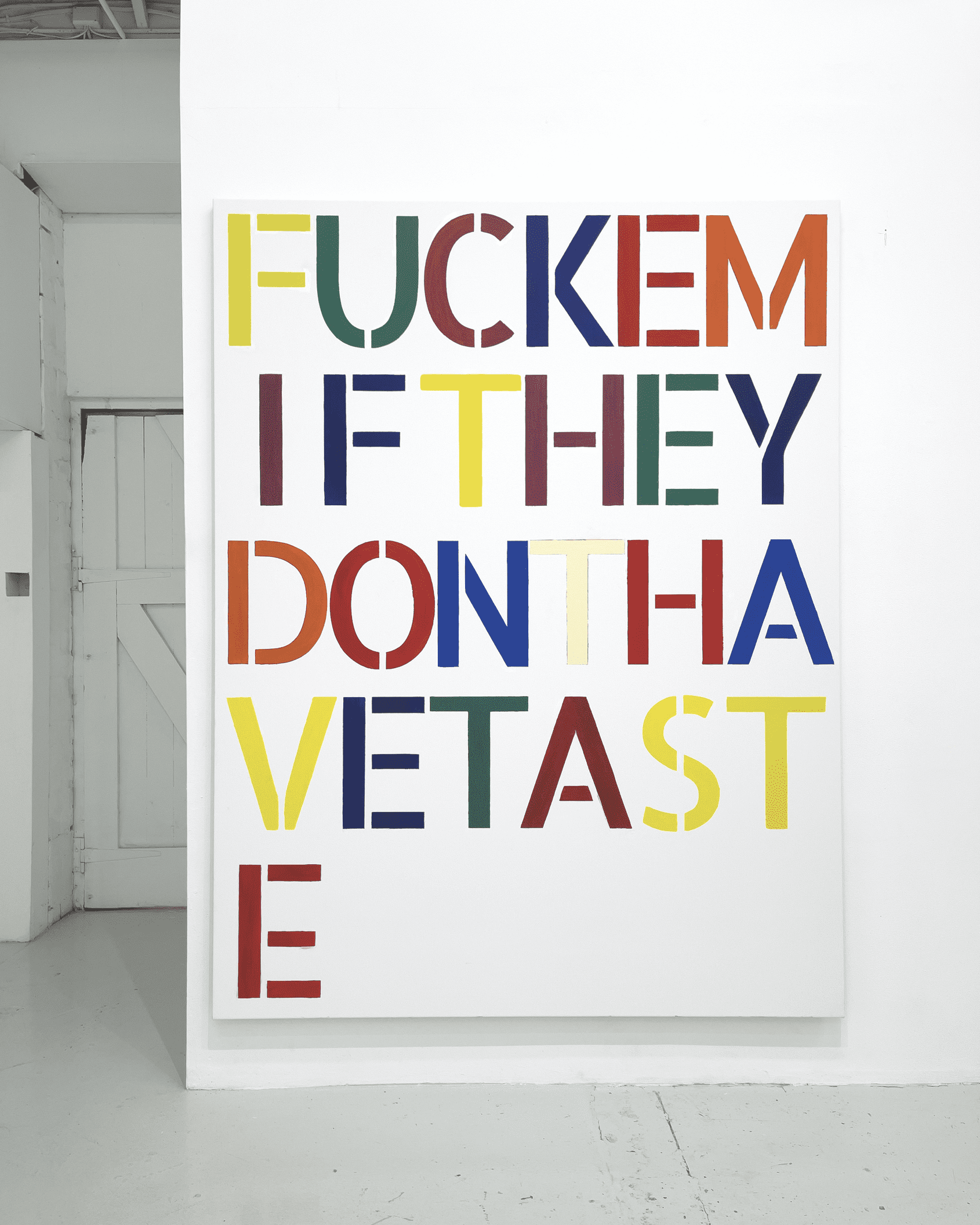

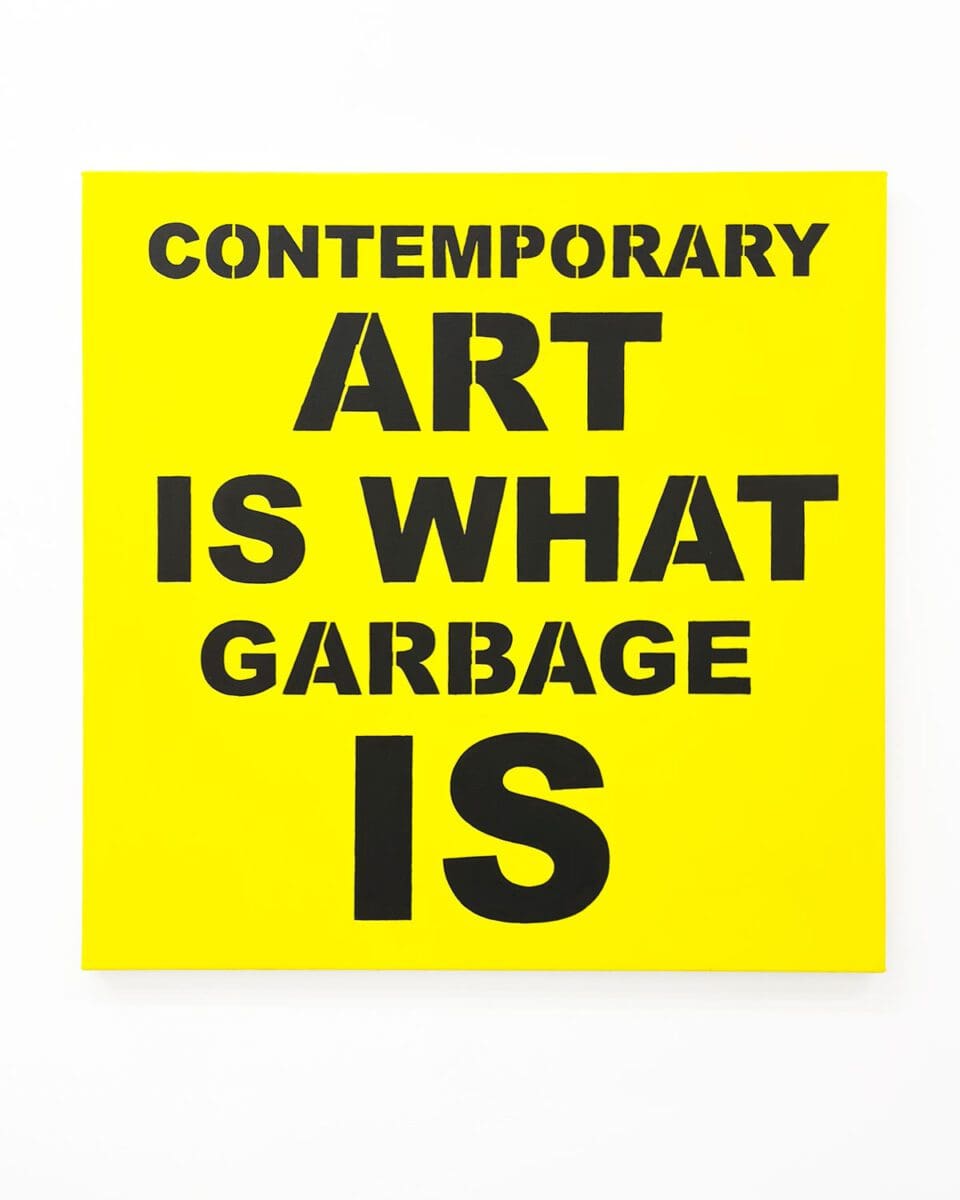

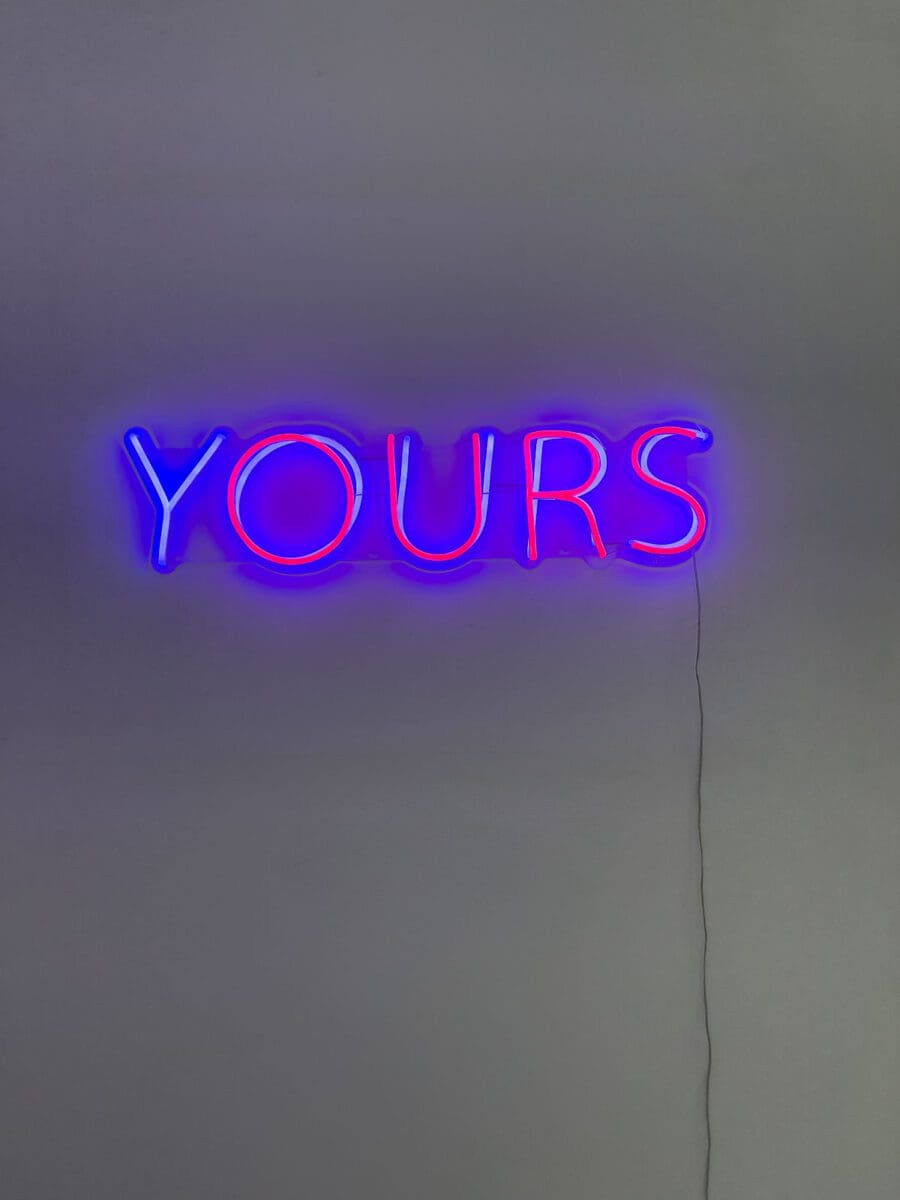

Like Kosuth, Qu has a penchant for a type of cheeky, deceiving simplicity with her signature works: what you see is most definitely not what you get. Imagine the neon signs one sees in restaurants and cafés, the slogans screaming at you while being enveloped in an atmosphere of absurd melancholia— except Qu takes this to its absolute limits.

Her work could be categorised as a kind of shanzhai— essentially meaning ‘fakes’, but more widely understood as a kind of bootlegging. It’s what Korean- German philosopher Byung-Chul Han defines as a cultural product that “fully exploits the situation’s potential”. Qu’s shanzhai might be described as ‘zoomer Jenny Holzer’: meaningful aphorisms cast in a loaded sheen, but with an irony-poisoned, extremely online, sensibility. For example, McDonald’s, 2019, depicts what could be interpreted as the ‘golden arches’ but it is also somewhat in the shape of a butt, with other orifices added through four lighting sequences. Underneath is text in all caps: THIS IS A MOUNTAIN YOU WILL NEVER GET OVER IT. A later work, DREAMING IS NO LONGER FREE WHEN I HAVE TO TAKE A SLEEPING PILL, 2021, reflects a similar sentiment. It is capitalism realism in a nutshell, memefied.

Of course, like many artists, Qu never thought she could be one. Post-graduation, she asked herself if she could develop an art career in Australia, especially as someone with little English skills and a migrant status. “Maybe I can’t, maybe I will never have an exhibition, maybe I don’t have any audience to see my work.” Yet, she thought to herself, “If I figure out what I should do, which is that I will find a way to live my life, pay my bills and create my art, I can be my own audience, my own art collector. And fuck everything else.”

Qu now has two poetry books—popcorn, porn of poetry, 2021, and This poetry book is too good to have a name/Logic poetry, 2022. In popcorn, her poems are presented in English and Chinese. The former is often a direct translation of the latter, and when asked if she thought about Chinese readers in mind, Qu says, “Many poems in that collection were first written in Chinese and then translated into English. I didn’t think about who can read Chinese; I kept the Chinese version for myself.”

Her recent exhibitions, An artist doesn’t need a label in 2022 and the title is no longer relevant in 2021, are a commingling of sincerity and irony. As usual, they are neon text-based sculptures, each potentially daring the viewer to interpret in a way that suits them, which further becomes a telling way to understand how that same person views art.

As seen from the show titles alone, Qu is adamant about making a statement. Her work feels borrowed from the aesthetics and sensibilities of riot grrrl and Dadaism, but imbued with a post-structuralist bent that points to the hectic globalisation and subsequent decontextualisation that is now permeating the world, where words now float freely in arenas devoid of meaning.

Global chains of capital fuel many people’s lives, and Qu’s LED neon artworks are no exception. Made in China, where she has built good relations with workers there, her work is not unlike the brightly-lit signs one sees everywhere in East Asia, which influenced Qu when visiting for holidays. “I feel pretty annoyed seeing bright and colourful advertisements everywhere,” she explains, “I had a revenge mentality where I wanted to use the same material to promote my cultural slogans.” This is Guy Debord’s theory of the “spectacle” taken to its limits.

Now Qu is showing at FUTURES Gallery in Melbourne. Not much has been revealed about the exhibition, but it will likely continue Qu’s questioning of art itself: “I think of conceptual art as [what Kosuth refers to as] an ‘art after philosophy’. It’s interesting to me to use a perspective to rethink the nature of art, by subverting the artwork to a certain extent.”

Art is a washing mashing that is washing itself

Chunxiao Qu

FUTURES Gallery (Melbourne VIC)

On now—23 September

This article was originally published in the September/October 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.