Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

Note: This feature was originally published in May 2018 ahead of Christian Thompson’s Ritual Intimacy opening at the Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA). Since then, Ritual Intimacy has toured to various locations throughout Australia, and is currently on display at John Curtin Gallery, WA, until 21 July 2019.

One of Australia’s preeminent contemporary artists, Christian Thompson, is returning to stage his first ever survey at the Monash University Museum of Art (MUMA), Melbourne. Thompson has spent close to the last decade in Europe and the UK, studying performance in the Netherlands before becoming one of the first Indigenous Australians to attend Oxford University, where he completed his doctorate in 2015.

MUMA director and survey co-curator Charlotte Day explains that she is wary of using pigeonholing terms like ‘mid-career.’ Instead, her interest is in bringing together the diverse threads of “artists who have produced a substantial body of work, or worked between certain types of practice.” The survey will feature a selection from 15 years of sculpture, photography, video, sound, installation and live performance, along with a newly commissioned work. It is co-curated by Day and Hetti Perkins, both of whom have worked closely with Thompson over the years.

One of the most important functions of the survey exhibition is to allow series created in isolation to be viewed side by side for the first time, suggesting new meanings and readings. For an artist, Day says, it’s often the case that “you know it in your head, the connectivity of things, but to physically experience it can be quite confronting, but a really good thing.” Experiencing the breadth of an artist’s practice also allows audiences to gain an understanding of where they fit within the broader context of Australian and international art.

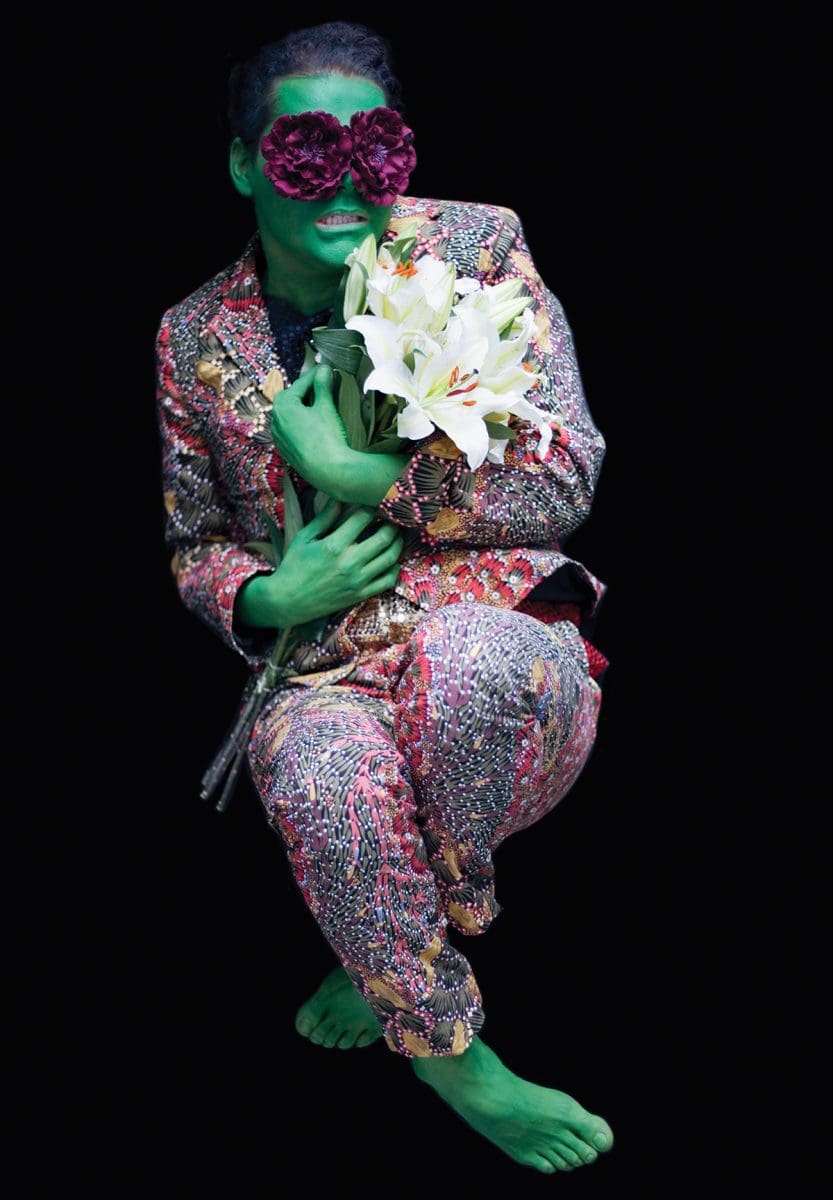

As is often the case, the use of the artist-as-model developed out of convenience. In a Radio National interview in 2015, Thompson explained, “I don’t think of them as being ‘myself’, because I think of my works as conceptual portraits. I’m really just the armature to layer ideas on top of.” He continued, “I really like the idea of wearing history, I like the idea of adorning myself in references to history.”

In the series Australian Graffiti (2007), Thompson’s head is garlanded by bottlebrush, kangaroo paw and eucalyptus flowers; in some images his face disappears completely, his individual identity either generalised as ‘native’ or subsumed by country. A more recent series, We Bury Our Own (2012), was made in response to the collection of photographs of Aboriginal Australians at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford’s School of Anthropology. Dressed in a crisp white shirt, the artist surrounds himself with objects of generic spirituality – candles, crystals, roses – and more specific references, including a model ship and an indigenous-print scarf. Thompson presents a complex picture of Indigenous identity, acted out through personal ritual before the camera. He has described the process as a “spiritual repatriation.”

Day says that the survey will include “a strong presence of works where [Christian] is performing, or the subject or carrier of the subjects. There are also works, like Heat [2010], featuring Hetti Perkins’ three daughters.” There will be a balance of iconic and lesser-known works. Day continues, “I’m interested in how in his practice there are very strong themes, for example playing with his identity and the nature of sexuality and gender… [and] over time he has become increasingly interested in broader cultural issues and histories, perhaps from living outside Australia for an extended period. You look at things differently from a distance.”

Although still in production at the time of writing, Day confirmed that the newly commissioned installation would include a sound component in Bidjara, Thompson’s father’s language, and a video component that focuses on the mouth. Regarding songs written and performed in Bidjara for his 2015 exhibition Refuge, Thompson has said, “I’ve tried to base [each song] around a traditional practice or idea… kinship, connectedness, camaraderie, rites of passage… I don’t translate the work, because then I think it starts to become didactic and explanatory. I want people to engage with the lyricism of the language, because it is an incredibly beautiful language.”

The use of his own body may be a convenient framework for Thompson, but it also implies an emotional and personal investment that lends his work power and immediacy. According to Day, Thompson is “an artist who really puts himself out there. I think it’s brave, how he is willing to challenge himself, particularly in moving from a more controlled situation with constructed photographs to live performances. There is an increasing acknowledgement of the importance of language, and finding a way for it to have a continuing life.”

Christian Thompson: Ritual Intimacy

John Curtin Gallery

17 May – 21 July 2019