While embracing hyper-political subject matter has become an of-the-moment approach for many artists globally, it’s one which has prompted others to cut on the bias, across the grain, and counteract it too. On first glance, it could be said that one such artist is Melbourne-based painter, Chris Bond.

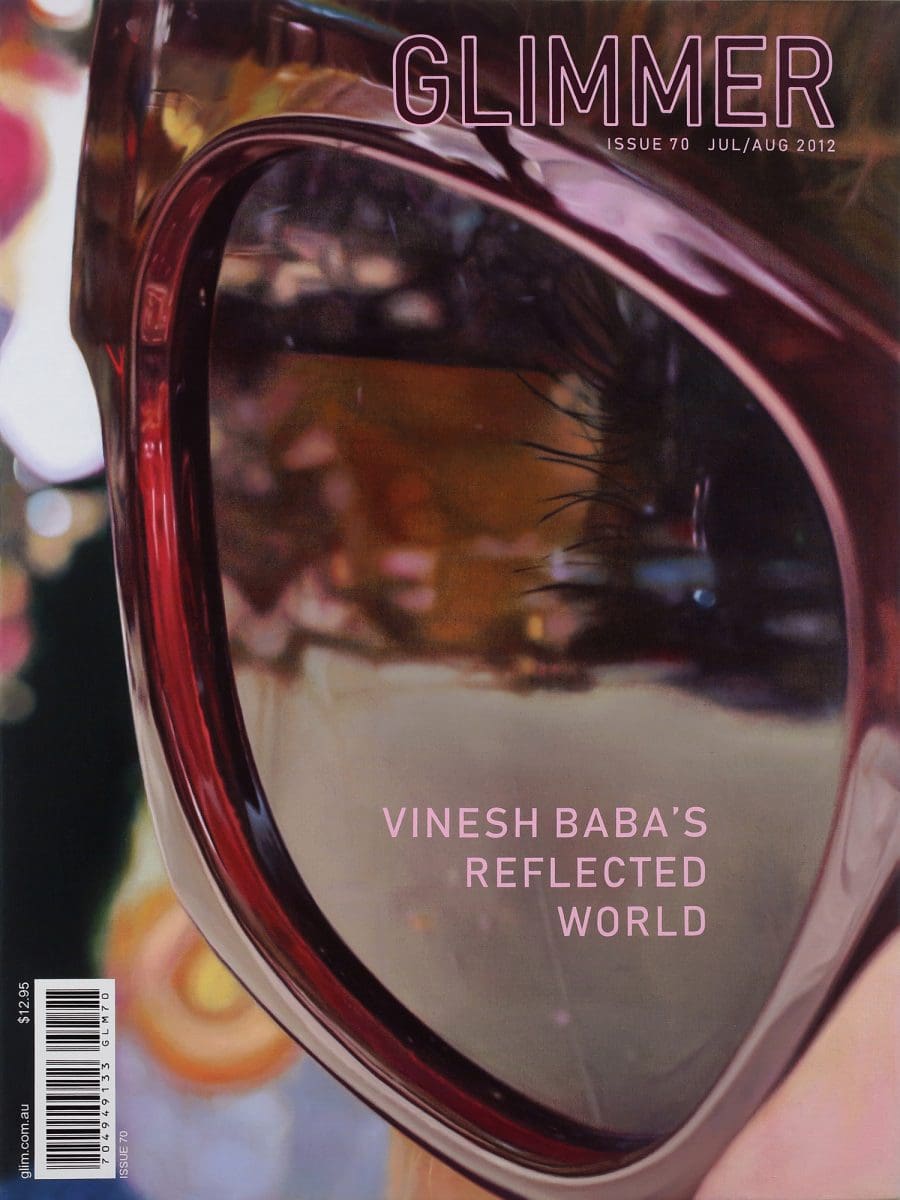

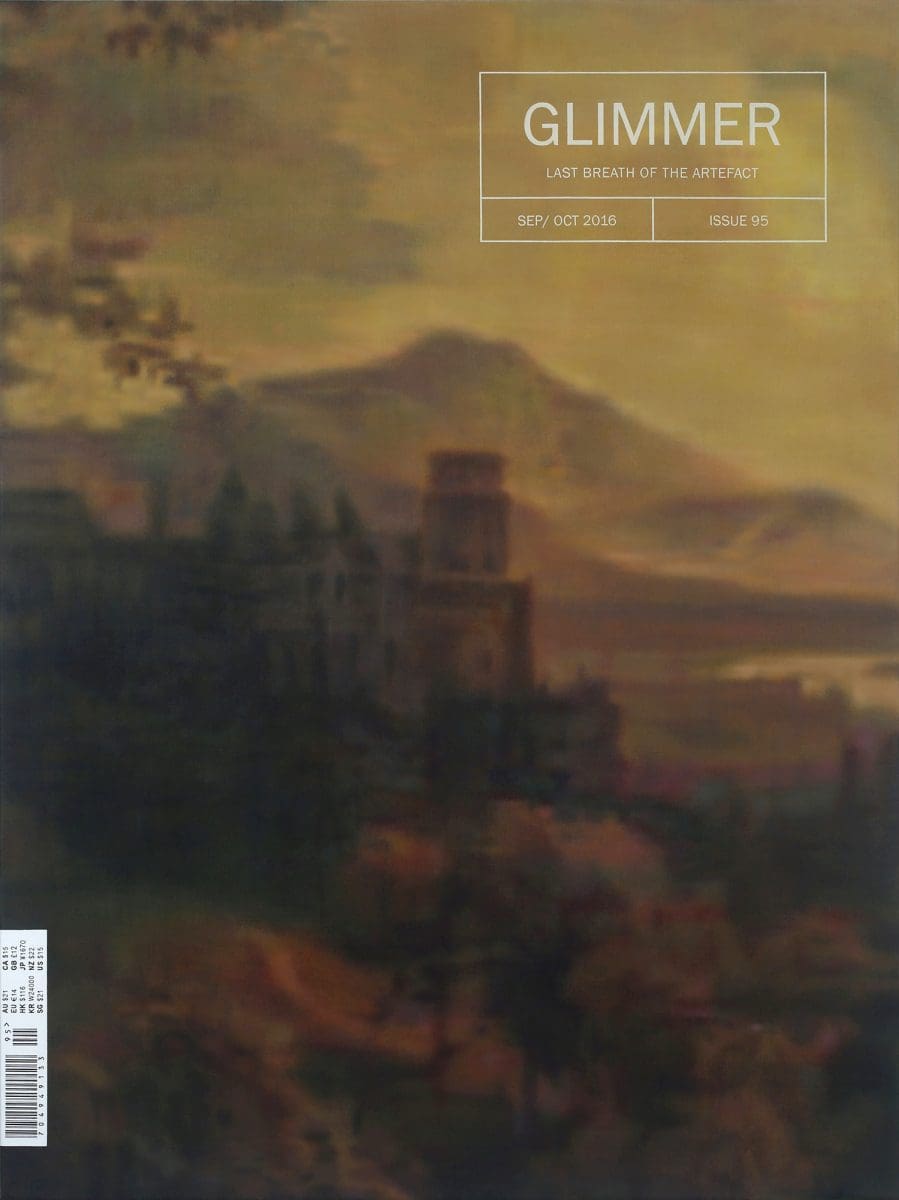

In his latest exhibition at Sydney’s Darren Knight gallery, Glimmer, Bond lures us through a trio of fictitious facsimiles painted with oil on linen. The works appear to depict three covers of a magazine titled Glimmer, which is said to have been active between the years 2001 and 2016. But the magazine never existed at all.

The first painting to catch your eye, Glimmer Issue 70, 2019, depicts the right lens of a pair of sunglasses, reflecting an illustration of the scene surrounding its wearer. Swapping pixels for paint, the work captures every detail you might expect to discover on the cover of a magazine today – from leading pull quotes, to a newsstand-worthy header – sparing little to no detail; not even the barcode. The result leaves you pondering whether what you are looking at is in fact a painting, or rather, a c-type photographic print.

For those familiar with Bond’s work, themes of eye-watering illusion and the craft of trompe l’oeil are all but unfamiliar.

Even his affinity with printed matter is something we’ve seen before, as in one of his earlier works, Vogue Hommes, September 1986, mirror, 2016. Shown as part of a group show at Geelong Gallery more than three years ago, the work emerged in response to Christian Capurro’s “erased magazine,” Vogue Hommes September 1986 #92, and was among more than 260 artistic responses globally, which worked to erase, and then reinscribe the original.

While Bond’s response to Capurro was based on a real issue of a 1982 cover of Vogue Hommes featuring the face of Sylvester Stallone, with Glimmer Bond has taken a step further to ensure that his viewer is in a rattling state of ephemeral confusion. A state in which he plays on our perceptions and expectations of truth and reality, only to pull the rug from beneath us on multiple levels. With these works, not only has Bond invited us to ponder the implausibility of his medium, this time he has inserted an entirely plausible, life-like subject into the mix too: a real-looking magazine, complete with a make-believe publisher, editorial schedule and mission.

In the past, Bond has often experimented with illusion in form, while his subject would feature objects of reality. Whether they be facsimiles of books which have been depicted with removed text, or a magazine pictured in reverse. However, this time, the illusion transcends both form and subject matter. Similar to the ways we encounter multi-layered truths on a day-to-day basis – whether they be online, in real life, or a cross-pollination of the two – Bond reaffirms the notion that we will always find ways to justify the cognitive biases we have about the truth; whether factual, or otherwise.

As Bond’s multi-layered illusions reveal themselves, questions about how political they really are begin to reveal themselves too. Amid a hyper-saturated attention economy, where being required to focus for longer than a few minutes – or even seconds at a time – is a rarity, perhaps his works are among the most political of them all.

In Glimmer, we are offered multiple layers of illusion, multiple points of discovery, and a line of questioning which multiplies like weeds. If given the time it deserves, Chris Bond’s Glimmer emerges as a blunt-force reminder of the naivety with which we float through a world cluttered with multiple truths, often forgetting that we’re bound by just one set of facts.

Glimmer

Chris Bond

Darren Knight Gallery

22 June – 20 July