Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

Chloé, the French nude by Jules Joseph Lefebvre, is an Australian cultural icon.

Chloé made its debut at the 1875 Paris Salon and won medals at the 1879 Sydney and 1880 Melbourne international exhibitions. In December 1880, Thomas Fitzgerald, a Melbourne surgeon, bought Chloé for his private collection.

Two years later, when Fitzgerald loaned Chloé to the National Gallery of Victoria, a furious debate erupted in the press. Public opinion was sharply divided over the propriety of displaying a French nude painting on the Sabbath.

Chloé spent the next three years at the Adelaide Picture Gallery, before Fitzgerald removed her from the public gaze.

After the surgeon’s death in 1908, Henry Figsby Young bought Chloé for £800 and hung the famous nude in the saloon bar of Young and Jackson Hotel, opposite Flinders Street Station in Melbourne.

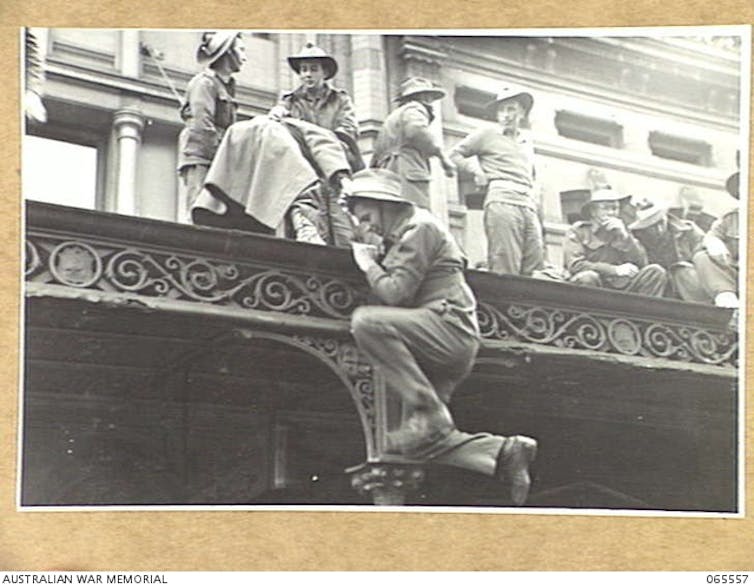

Enjoying a drink with Chloé at the hotel has been a good luck ritual for Australian soldiers since the first world war.

According to the 1875 Paris Salon catalogue, Chloé depicts the water nymph in “Mnasyle et Chloé” by 18th century poet martyr André Chénier. Toes dipped in a puddling stream, longing and heartache etched on her lovely features, she listens for the voice of her lover.

Chloé was created in the winter of 1874-75. France was still rebuilding after its defeat in the Franco Prussian War and the Versailles government’s brutal repression of the revolutionary Paris Commune.

Newspapers in France and around the world described women who supported the Commune as lethal pétroleuses, or petrol carriers. The women were often blamed for destructive acts of arson carried out by Versailles troops during The Bloody Week.

Jules Lefebvre claimed his working class model for Chloé was involved with former Communards. She may have fought alongside other girls and women, and witnessed the widespread bloodshed that stained the streets of Paris red in 1871.

This volatile chapter in French history has been absent from Chloé mythologies. But Chloé was painted in the wake of war and revolution and of women’s inspiring activism, as women challenged the class and gender barriers that had limited their opportunities.

The ritual of having a drink with Chloé at Young and Jackson Hotel, opposite Melbourne’s busiest railway station, began after Private A. P. Hill, who was killed in action, put a message in a bottle and tossed it overboard.

When the bottle was found in New Zealand in January 1918, his message read:

To the finder of this bottle. Take it to Young and Jackson’s, fill it, and keep it till we return from the war.

The hotel and Chloé proved irresistible for returning soldiers.

By the start of the second world war, Chloé and Young and Jackson’s were so enmeshed in military mythology they were included in the 2/21st Australian Infantry Battalion’s official march song:

Good-by Young and Jackson’s

Farewell Chloé too

It’s a long way to Bonegilla

But we’ll get there on stew

Tragically, on February 2 1942, the B and C Companies of the 2/21st Australian Infantry Battalion were massacred by Japanese forces at Laha Airfield on the Indonesian island of Ambon. Those who weren’t killed became prisoners of war.

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, the Australian prisoners’ hopes for liberation were frustrated when Japanese officers refused to give them radio access.

When they finally got a radio transmitter their SOS message was received on the neighbouring island of Morotai. The men were asked questions to prove they were “dinki-di Aussies”.

One of the first questions Melbourne soldier John Van Nooten was asked was “how would you like to see Chloé again?”

When Van Nooten replied “Lead me to her”, the operator asked “where is she?”

Van Nooten responded with Young and Jackson’s, finally convincing the operator he was Australian.

In his 1945 article Seein’ Chloé, West Australian journalist Peter Graeme claimed:

Chloé is to Melbourne what the Bridge is to Sydney. From the soldier’s point of view of course. All over Australia you meet men who have seen her […] Chloé belongs to the Australian soldier.

Graeme recalled meeting a soldier at Young and Jackson’s who drained three drinks in front of Chloé. When he asked the soldier why he drank the beers in quick succession, the soldier said he was honouring a promise he and two mates had made to Chloé.

The three of them had pledged to have a drink with her when they returned to Melbourne. His two friends never returned, buried at Scarlet Beach in New Guinea.

As Graeme concluded in his poignant tale, Chloé may have been:

the symbol of the feminine side of his life. That part which he puts away from him, except in his inarticulate dreams.

The soldier’s grief for the mates he lost, and the comfort drinking with the painting gave him, seems to resonate with the longing in Chloé’s melancholy expression, and the war-torn history behind this celebrated Melbourne icon.![]()

This article was written by Katrina Kell, Honorary Research Associate, Murdoch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.