Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

The Qing dynasty was still ruling, Hong Kong had been ceded to Britain and the whole country was moving into a time of calamitous civil unrest when photography found its way to China in the 1840s, soon after the process was invented in France and England.

The Chinese embraced the medium right from the start and have been recording goings-on across the country – revolutions, farming, street life in big cities, remote communities in Tibet – ever since.

Now an exhibition at the Monash Gallery of Art surveys photography as it has unfolded in China over the past 150 years, shedding light on ways of life that have often been out of view from the West.

China: Grain to Pixel was shown last year at the Shanghai Center of Photography, recently established in a former aircraft hangar and – in a sign of the times – the first public space in Shanghai dedicated to photography.

The exhibition will be the largest survey of Chinese photography ever held in Australia, in a cross-country collaboration that MGA director Kallie Blauhorn expects will result in an exhibition of Australian photography being held in Shanghai in the next 18 months.

Blauhorn, who visited China last November, says she had a “very strong response” to the exhibition and immediately thought it a neat fit with the MGA, given the large number of nearby residents of Chinese descent.

She believes the exhibition – “an intriguing insight into the somewhat obscure history of Chinese photography from an era of black-and-white documentary images through to imaginary contemporary visions” – will speak to a wide cross-section of Australians at a time when people are becoming more curious about life in China.

This thinking is backed up by HS Liu, the Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist who founded the Shanghai Center of Photography and who has also spoken about the “burgeoning interest in photography in China internationally”. In the forward to the catalogue for the Chinese exhibition, Liu says a number of recent publications (both in China and abroad) have examined historic and contemporary Chinese photography and that the number of domestic photography festivals in China is multiplying.

That said, Chinese authorities are not up for having everything opened up to international perusal and, when we spoke, Blauhorn was in the midst of negotiating with the Chinese government about “a handful of works” that were deemed too politically sensitive to send to Australia.

Even without those works – related to the 1960s Cultural Revolution – she says the exhibition reveals much about China’s history and about how photography in China has evolved both stylistically and technologically.

Put together by British curator and art historian Karen Smith, who has specialised in contemporary art in China since 1979 and has lived in Beijing since 1992, the exhibition includes about 150 pieces by 70 photographers. In her catalogue essay, Smith says that together they “lay claim to a wide-ranging body of images and approaches that, via myriad topics and all manner of formats, reveal China through recent decades until today in all its rich complexity”.

Fifty years since the start of the decade-long Cultural Revolution – that left many millions malnourished and uprooted and, according to a recent New Yorker article, up to one and a half million executed or driven to suicide – viewers will see how Chinese documentary photographs of the 19th century evolved into the promotion of communist ideologies in the 20th century and then into the exploration of more personal perspectives in recent decades.

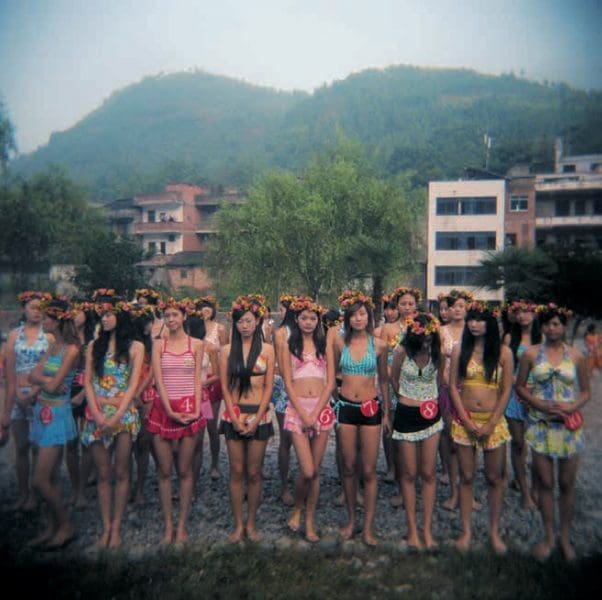

There are photographs of people and nature, of mysticism and the reality of daily life. Some images are nostalgic and others futuristic. Some works attempt to speak broadly on it all.

Blauhorn says when she saw the exhibition in Shanghai she “loved the expanse of it”; there was everything from old images of Mao Zedong to fluoro abstractions to photographs that bridge the divide between traditional and contemporary worlds. “The photographs go from social documentary to photo-journalism to artistic.”

Smith has chosen works that lay bare the changes in photography, from the mid-19th century pictures taken by visiting foreigners to photojournalistic pieces like those by Sha Fei (1912–50) that include glimpses of the Great Wall to invoke China’s “strength and durability”, to the staged, fantastical concoctions by contemporary artist Maleonn, a one-time director of video clips. It’s an evolution that never stops.

China: Grain to Pixel

Monash Gallery of Art

5 June – 28 August