Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

We often like to think of nature, particularly wilderness, as external to humanity. In theory, it might be. Yet nature is customarily measured in human terms, through the lenses of ecology, boundary politics, religious interpretation and artistic reimagining. We cannot help but overlay our beliefs, memories, sensations and technology onto nature, and so we will always see ourselves reflected in it. To paraphrase cultural geographer Denis Cosgrove; nature is an idea, a human one.

Supernatural is an expansive exhibition project from the White Rabbit Collection, featuring works by 33 contemporary Chinese artists who describe what they see reflected in nature: historic traditions, enchantment and hypothetical futures.

“In ancient China,” says curator David Williams, starting at the beginning, “mountains were the home of the gods.” Invested with the presence of the Immortals, nature was venerated in artworks and poetry. In the Shan Hai Jing, the ancient geographic text, locations were mapped according to habitation by fantastic creatures and phenomena (phoenixes, trickster foxes, magic mists). Instead of coordinates, stories are given, embedded in place names such as Departing-Doves-Mountain, Supported-Pig-Mountain or Elephant-Bones-Mountain. This is a tradition in which land, magic and the lyrical stamp of the storyteller are inseparable.

At its height in the Song Dynasty (960–1279 CE), ink painting sought not to replicate the visible world but to embody Buddhist, Daoist and Confucian principles. The artists of Supernatural are the successors of this practice. “Generally speaking, Chinese artists are knowledgeable and respectful of their traditions, but feel free to adapt the mist-wreathed mountains of traditional ink paintings to the globally-connected ‘new China’ of mega-cities, high speed rail and high-tech industry,” says director Judith Neilson.

Many of the artists live and work in big cities like Beijing or Shanghai, whose pleasures and ills echo those of Australian cities. “These are exciting, creative metropolises,” says Williams, “but their inhabitants grapple with issues of apocalyptic air pollution, unbelievable traffic, fears about food and water safety, over-population and the constant surveillance that now includes facial recognition technology. It’s unsurprising that Chinese artists are exploring the Anthropocene, creating morality tales that are a wakeup call to us all.”

Each artist finds a place for these omens within the sensibility of historic painting; coupling visual order and quietude with sensational augury. Chen Wei’s series of photographed dioramas imagine the logical endpoint of urban overcrowding. Future and Modern (2014) reduces city living to three elements: high-rise, neon and smog. It’s a canister hardly more habitable than a jar with holes poked in the lid. Despite this, the image is still and velvety, redolent of traditional painting.

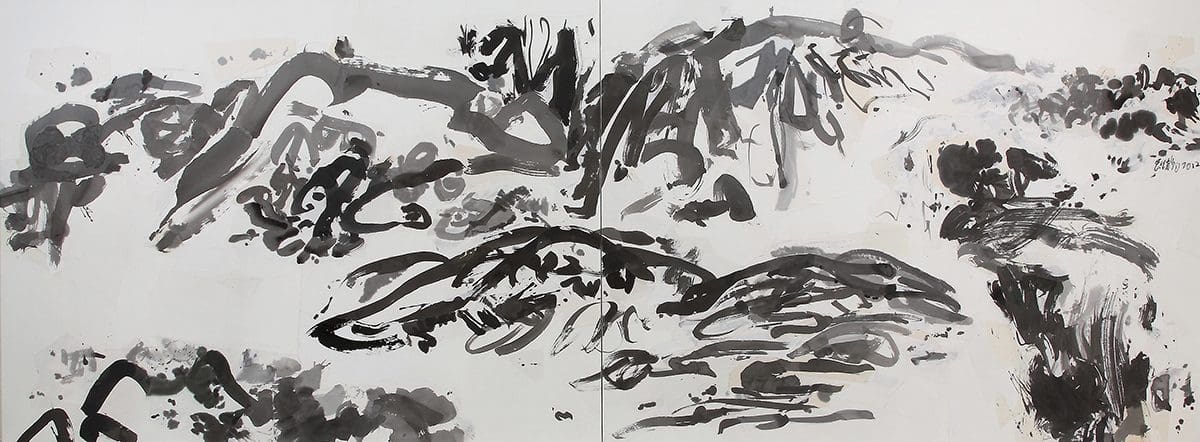

The influences of the Supernatural artists extend past Chinese tradition, courtesy of “porous national borders and instant online communication,” says Williams. “Emily Shih-Chi Yang studied in the USA before returning to Taiwan. Her expressive technique owes something to the New York School of gestural abstract painters.” The Blessed Mountains (2012) is a cacophony of richly gestural brush marks on rice paper, which Yang dismantled and reassembled, creating a scrambled vision of, not landscape, but landscape-ness.

Beijing-based painter Yang Shen’s Ducks Mocking Sailor (2016) departs even further from tradition. By a riverside, a mariner is tormented by a painted swarm of jolly skulls and rubber duckies. This cartoonish landscape derives from the utopias of children’s books, sci-fi and advertising. “The Day-Glo colour, the expressive brushwork,” says Williams, “they reveal a whimsical nostalgia for a future that never quite arrived.”

With a billion people expected to relocate from rural to urban homes by 2030, cities are engulfing surrounding hinterlands and putting pressure on wilderness and agriculture. For metropolitan citizens, the distance between daily life and the lakes and mountains of art history is widening. Zhou Xiaohu’s Garden of Earthly Delights (2016) protests this gulf. The video retells the fables of Daoist master Zhuangzi, which advocate for a morally fluid and spontaneous lifestyle in nature, free from inhibition and unthinking compliance. Enlisting a puppet troupe from Zhejiang province, Xiaohu built eight marionettes to perform the fables alongside “bleak, post-industrialist mega structures: a dam, a power plant, an abandoned mine,” says Williams. Woe betide we who relinquish nature and individualism.

Supernatural is split across four floors, each offering a distinct biome: urban, rural, sea. The ground floor will house the exhibition’s most surreal and speculative artworks, representing something of a netherworld or Tiān (celestial Heaven) landscape: a place from which the supernatural emanates to populate past, future and imagined environments.

Supernatural

White Rabbit Collection

7 September – 3 February 2019