There is not much to the standard neon light: a glass tube, an invisible gas and a zest of electricity. Engineered by French chemist Georges Claude in 1910, and first seen flickering outside a Parisian shopfront, its name derives from the Greek neos, meaning ‘new’. An asset in the economy of attention, neon’s strange glow has become central to the architecture of city nightscapes. It is also the main element of Cerith Wyn Evans’ …. in light of the visible at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney (MCA). Despite its ubiquity, the artist deploys the material with a poetry that is uncanny, sublime and, indeed, novel.

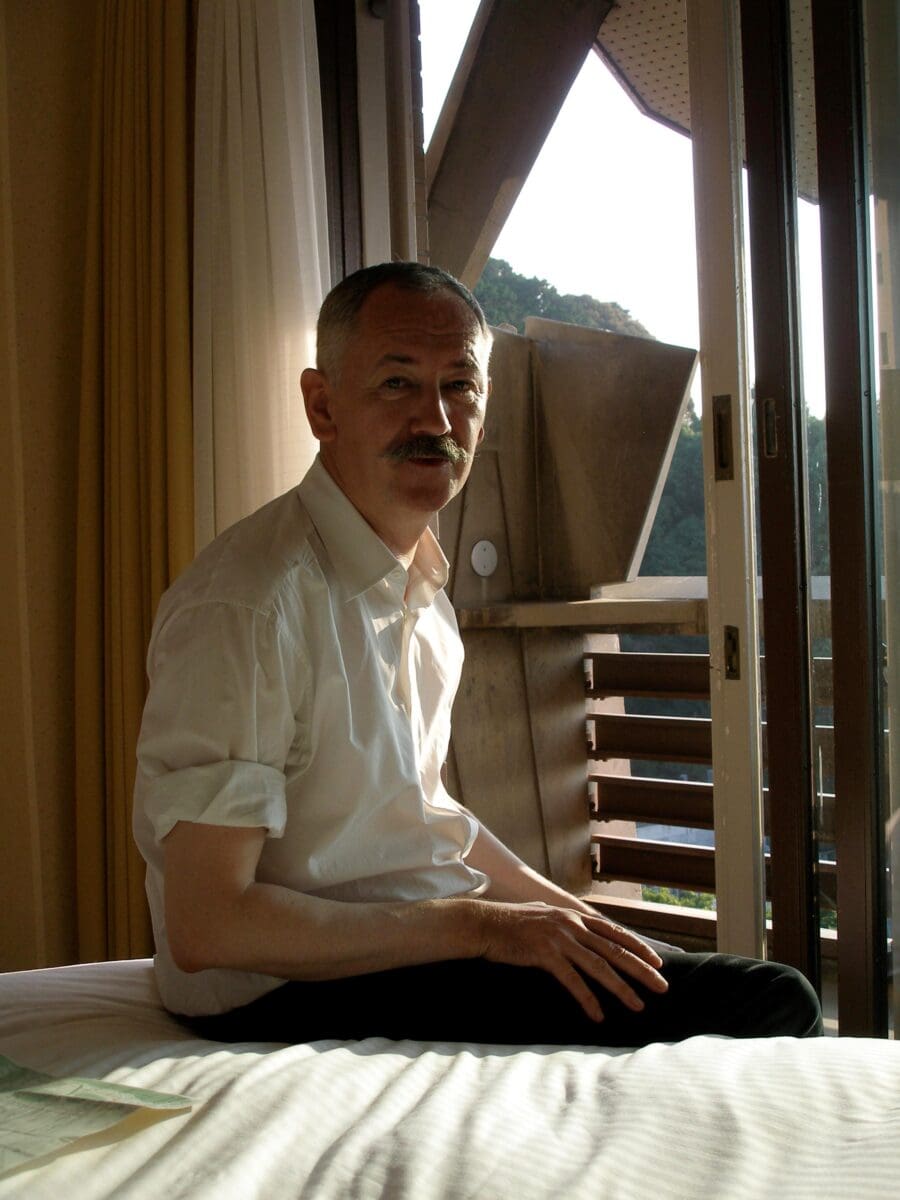

“Cerith is one of contemporary art’s great visionaries,” exhibition curator Lara Strongman tells me, producing work that is at once “conceptually brilliant and profoundly emotional.” Evans’ work has been exhibited around the world and in 2003 inaugurated Wales’ national pavilion at the Venice Biennale. …. in light of the visible is the artist’s first major exhibition in Australia.

Born in 1958 in Llanelli, Wales, a teenage Evans’ encounter with the work of artist Michael Craig-Martin proved revelatory. A glass of water was accompanied by a text explaining that the object had been transformed into the work’s namesake: An Oak Tree (1973). Five decades on, Evans is harnessing language and viewers’ imagination to breathe new meaning into objects.

“He always goes beyond the fear of pooling knowledge,” wrote Hans Ulrich Obrist, director of Serpentine Gallery, London. This reservoir of knowledge runs deep, with each work being an “active agent in conversations that take place across time and space, between Cerith and other artists, musicians, writers, gardeners, philosophers, physicists,” says Strongman.

The artist cut his teeth as a filmmaker producing short, experimental films, counting Derek Jarman among his collaborators. In the 1980s, he was also deeply involved with London’s experimental music scene, producing films and music videos for bands such as The Smiths, The Fall, Throbbing Gristle, and Psychic TV. These experiences coalesce with a wide breadth of influences, ranging from Marcel Duchamp, John Cage, William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin, to scientific ideas of probability theory and dark matter, studied by the artist during visits to CERN in Geneva.

Despite the works’ complex theoretical footing, Evans asks his audience to resist interpretation. He is partial to art historian Mark Cousins’ words, who likened the experience of his work to being “a deaf man staring at a radio”. Evans’ work privileges atmosphere over article, resonance over resolution.

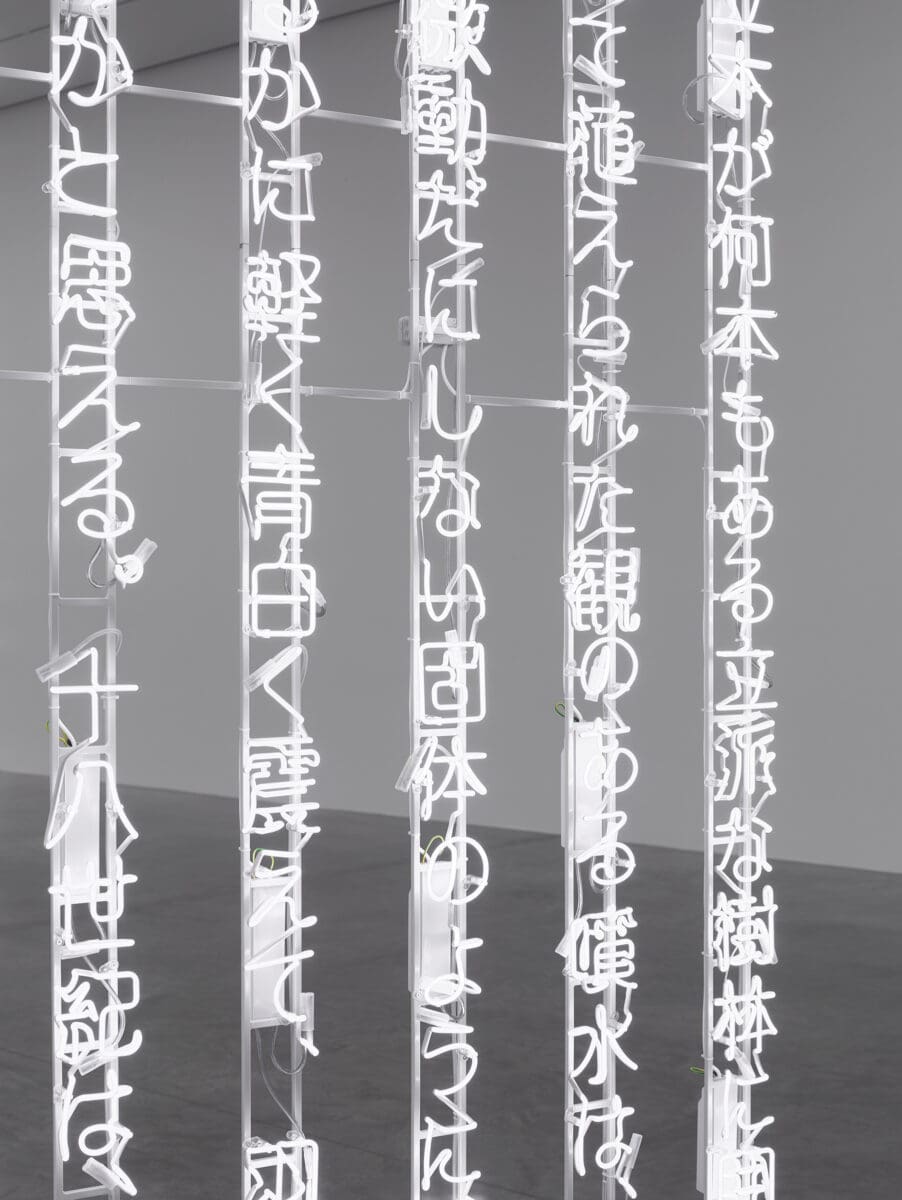

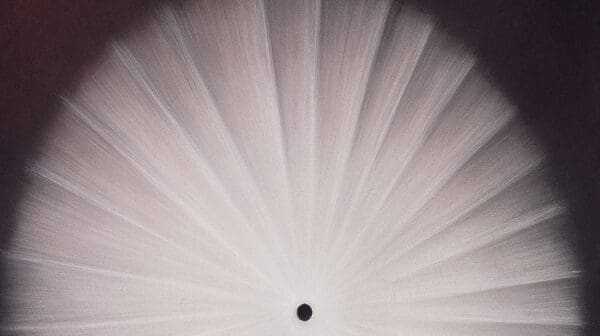

But still, how do literature and music leap into neon light? In the case of the exhibition’s centrepiece F=O=U=N=T=A=I=N (2020), an unbroken paragraph from Marcel Proust’s Sodome et Gomorrhe (Sodom and Gomorrah, 1921–22) is translated into Japanese. Neon kanji characters hang suspended on a porous wall that stretches ten metres long and stands three metres tall. The characters narrate Proust’s passage about a fountain, its splashing droplets made luminous by the sun. Here, language folds into form: each character a delicate sculpture lit internally rather than by the sun, the scene left to be imagined by those who consult the accompanying translation.

At large, the exhibition imagines the gallery as garden. Far from a cut-and-paste of previous works, the artist considers each exhibiting space deeply, responding to the “volume of a room, its light, its auditory properties, [and] its history”, making the experience of the work “entirely differently from place to place”, Strongman observes. At the MCA, ambient sounds from the outside whisper into the room as part of Two Gravity Gongs (2025) and uncovered windows frame views of the harbour. Distant trees, glittering ocean, and ferries to-ing and fro-ing become integral to the work, collapsing artwork, viewer, and environment.

For Evans, the garden is both “talisman and method”, a structuring principle that shapes how this exhibition unfolds. As Strongman explains, the garden offers a model for intuitive, non-linear experience: “You can make a purposeful line through the garden or you can drift, stopping and starting wherever you like … you can never experience a garden the same way twice.” In Still Life (In course of arrangement…) (2025), plants rotate slowly, barely detectable, on turntables mirroring their imperceptible cellular growth. Spotlights on each lend a “cinematic quality”, offering a microscope to their movement. The botanical selection is deliberate—there were citrus trees in Athens, Japanese pines in Tokyo, and at the MCA various species native to Warrane, selected in collaboration with Aboriginal-owned plant nursery, IndigiGrow.

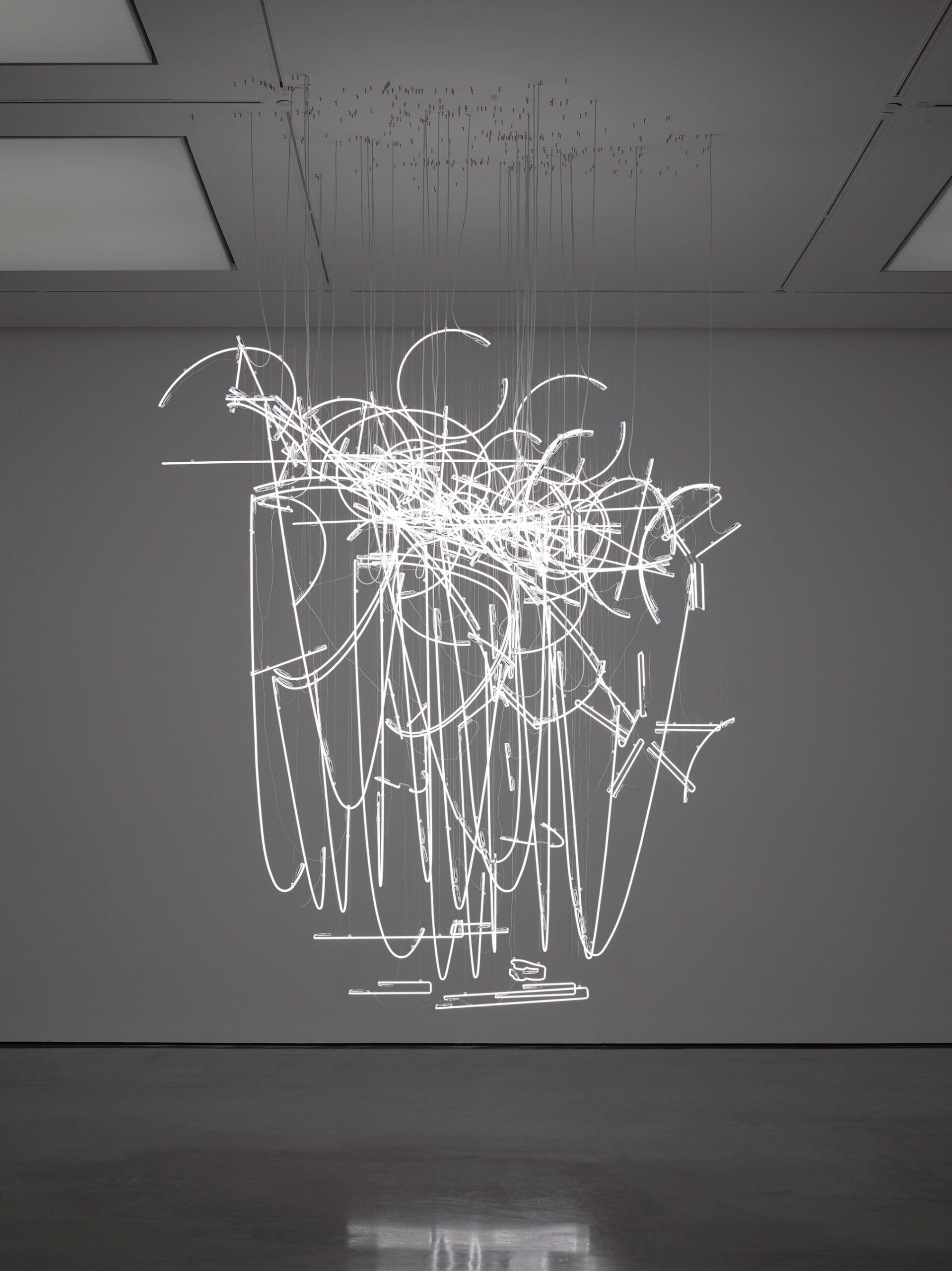

Neon Forms (after Noh) (2015–ongoing) draws on the artist’s long-standing fascination with Japanese Noh theatre. Suspended in space, unruly scribbles of white light echo kata diagrams—choreographic notations that guide performers through the stylised movements central to the form’s centuries-old tradition. Evans’ approach resonates strongly with 14th-century Noh because despite the intricacy of its instruction, its aesthetics lean towards the allusive. Removed from their context, the choreographic scores enter a new universe of meaning, becoming, in the words of Zoe Stillpass, curator at the Centre Pompidou-Metz, “a disembodied dance without the dancers”.

In re-situating forms, Evans exposes a beauty often latent in its original setting. While his work is in dialogue with a pantheon of historical figures and ideas, it is ultimately the viewer with whom it most intimately converses, loosening inherited systems of knowledge and letting them flow from new vessels. Like The Oak Tree he encountered as a teenager, each work is animated by audience imagination. Across the chorus of light, shadows, sound, and kinetic plants of …. in light of the visible, more than anything, the profound sensuality of it all draws you in.

…. in light of the visible

Cerith Wyn Evans

Museum of Contemporary Art

(Sydney/Gadigal Country NSW)

Until 19 October

This article was originally published in the July/August 2025 print edition of Art Guide Australia.