Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

Since the 1990s, American photographer Catherine Opie has been internationally renowned for capturing friends and family, queer domestic life, and defining political moments. Entwining identity and sexuality, kinship and community, Opie’s first Australian survey is now showing in Melbourne.

When Los Angeles-based photographer Catherine Opie was eight years old, she completed a school assignment on early 20th century American photographer Lewis Hine. Soon after, she requested a camera for her ninth birthday. She has been photographing the world around her ever since. Family, friends and community have remained consistent subjects in her visuals, and it is this desire to document community and the constructs of identity that endures as a staple of her photographic practice.

For over 30 years, Opie has been amassing an immense oeuvre covering queer portraiture, ceramics, abstract landscapes, collage, documentary photography and film. Providing visual commentary on the American cultural landscape with photographic series devoted to urban mini-malls, butch lesbian communities, Los Angeles freeways and Californian surf culture, Opie focuses predominantly on marginalised communities and those who belong to them.

While Binding Ties at Heide Museum of Modern Art is the first survey exhibition of Opie’s work in Australia, her work was exhibited previously at Heide in 1994, when 18 of Opie’s photographs were curated into the group exhibition Persona Cognita. Curator of Binding Ties, Brooke Babington, believes it is time to reassess Opie’s work considering how much our understanding of gender and sexuality has shifted.

“The limits of community and family have become increasingly porous, and our concept of citizenship has become more inclusive and accountable,”

Babington says. “I feel that on a personal level but also collectively, our sense of community has become more refined. While her [Opie’s] historical work deals with these issues and is the most well known, her overarching practice is a lot broader. This is reflected in the theme of affiliation underpinning Binding Ties. It goes through four stages where we consider individuality, cultural identification, community and family.”

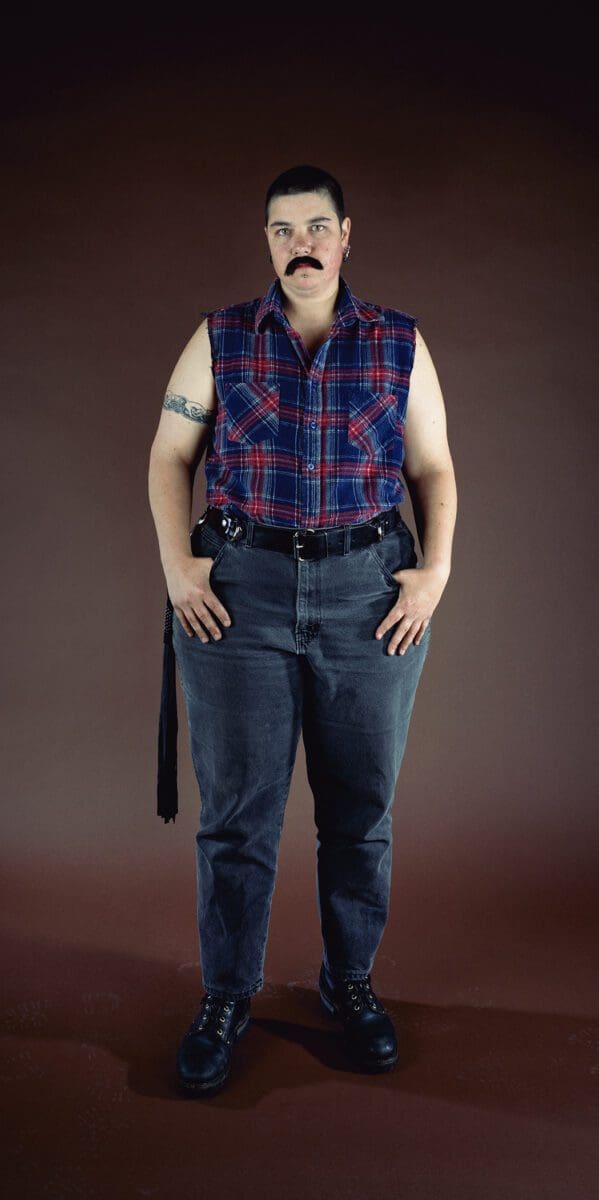

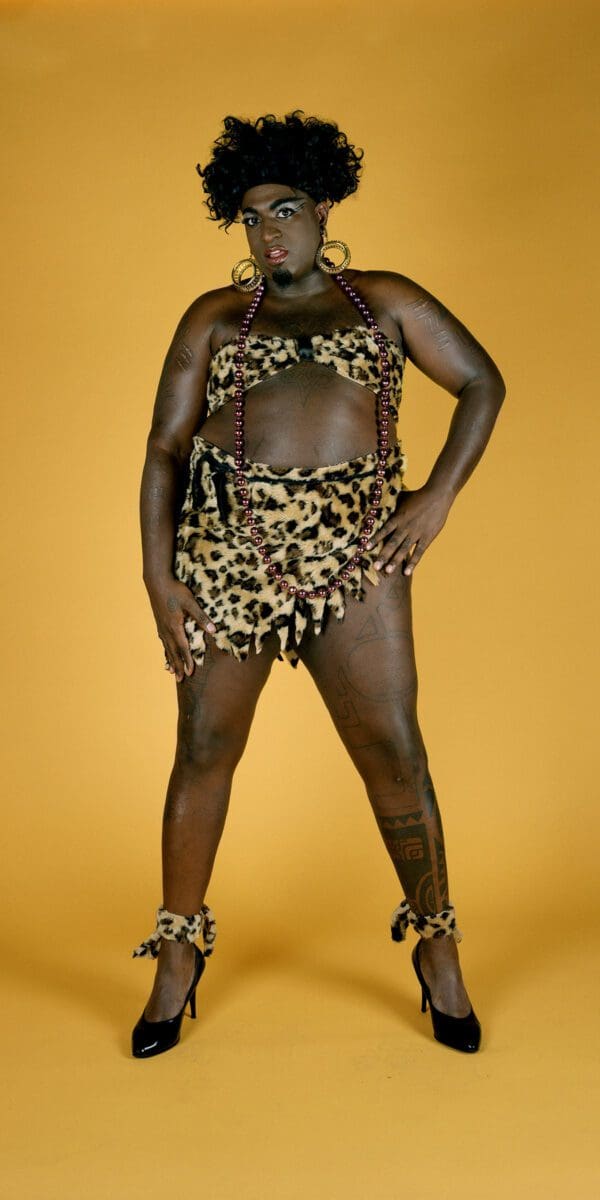

The importance of the chosen family over the traditional nuclear model is a clear focus running through Binding Ties and Opie’s work in general. The bonds of kinship we form with our chosen families and extended communities are vital sources of support and connection. This is particularly evident in Opie’s Being and Having, portraits taken in the early 90s, where she produced numerous images of friends in the LGBTIQ+ community and BDSM groups. Mimicking the style of Hans Holbein’s royal, Renaissance-era portraits, many of these images placed the sitter centrally in front of a single colour background.

Speaking in a video interview with the Tate gallery in 2018, Opie explained the broader implications of works like those in her Domestic series, 1995-98, where she photographed queer families and couples in their home environments. “Without representation you can’t make change happen,” Opie explained. “Community is a way to begin to articulate the more complex ideas around that.”

Pouring over the photo essays in LIFE and Look magazines as a child, Opie’s early experiences of image making shaped her view of how individual photographs speak of a larger narrative. Representations of the individual give way to depictions of the wider cultural landscape and Opie has taken in everything from high school football games in Texas and ice fishing houses in Minnesota, to Californian surfers and Elizabeth Taylor’s home in Bel Air.

In a 2022 interview with UK magazine The Gentlewoman, Opie said, “My work really does need me to be out in the world listening, talking, looking, thinking. A lot of my work is about revealing different ideas of systems: either community or identity. But what is identity? And how do we begin to unpack it? And how do we unpack it in relationship to physical structures?”

Travel has been a regular occurrence throughout Opie’s practice. At various times, Opie has crisscrossed the US to photograph the crowds at Obama’s inauguration, the 2007 Women’s Marches and the Tea Party gatherings.

Most recently, she travelled in an RV from Los Angeles, California to Richmond, Virginia, documenting monuments and memorials as she went. In Untitled #4 (from the monument/monumental series), 2020, the viewer is positioned looking up at a monument of confederate civil war general Robert E. Lee, the whole statue covered in a tangle of graffiti rising like an angry tide—a potent visual reflection of protests linked to the Black Lives Matter movement.

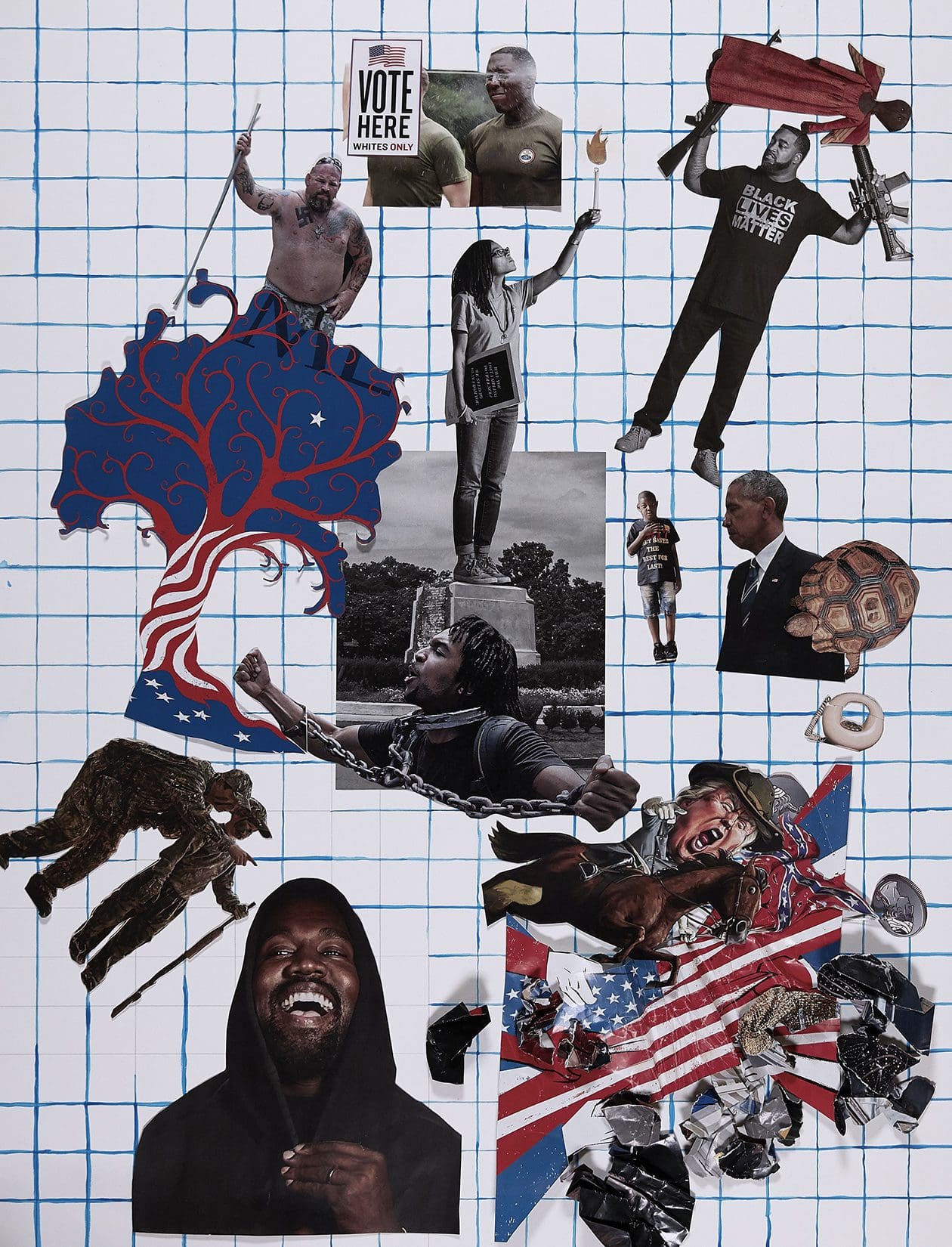

Prior to the monument/monumental series, Opie created Political Collage, 2019, a series of video works displayed on digital kiosks designed to look like iPhones. Each collage illustrates a political issue—gun laws, immigration—all topics high on the agenda of the Trump administration. Animated using stop motion, the collages are populated with cut outs from books and magazines skittishly moving about on a hand painted blue grid background. During her 2021 Monsen Photography Lecture, Opie admitted, “It was almost impossible not to make political work at this time.”

Also influenced by the portraits of Dutch photographer Rineke Dijkstra and the work of American photographer Dorothea Lange, Opie finds honesty and beauty in things unseen or hidden. By photographing the smaller pockets of society, politics and everyday life, Opie unearths the intricate communal fabric that binds us together. “Every viewer comes with a different experience,” Opie explained to the Tate. “It’s about the humanistic expectations that we have gazing upon a portrait, a landscape, or a situation. If you can walk away having a better understanding and openness of being human, that is what I care about the most.”

Catherine Opie: Binding Ties

Heide Museum of Modern Art

(Melbourne VIC)

Until 9 July

This article was originally published in the May/June 2023 print edition of Art Guide Australia.