Poetics of Relation

Tender Comrade, currently on show at Sydney’s White Rabbit Gallery, creates a new vocabulary of queer kinship by reimagining the relationship between artworks, bodies and space.

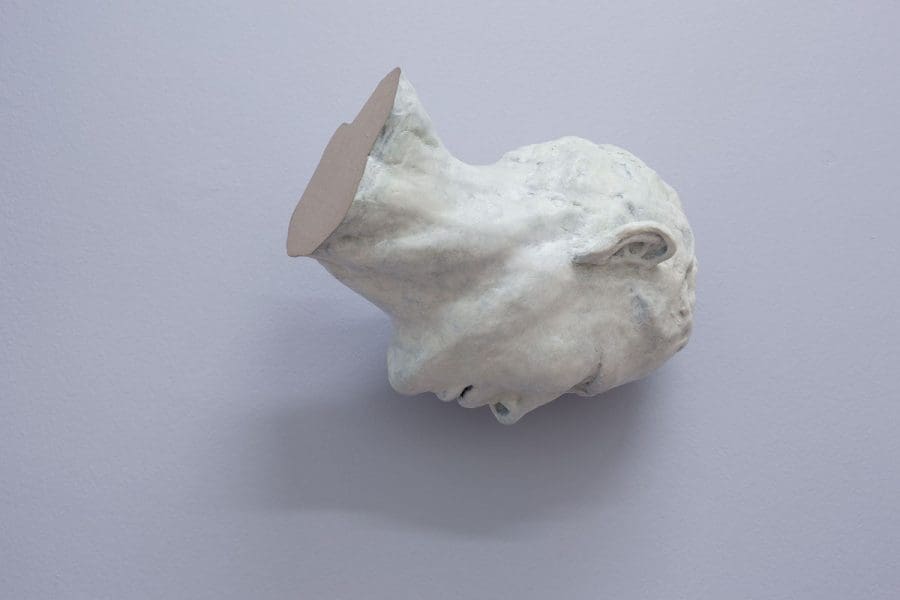

Her/e, an exhibition by Cate Consandine at Sarah Scout Presents in Melbourne, was riddled with dense ambiguous zones within both landscape and psychological-scapes. The show consisted of a video work, A Woman of the Future (2016) and three sculptures of heads, presented one per room, and hung at precarious angles on walls painted lilac. Her/e felt like a presentation of a shifting, unsettled state and unplaced desire. Caught between the ephemerality of film and the solidity of sculpture and installation, the works elastically expanded into a charge that permeated the gallery’s air between the sparse hang of works.

A woman walks across the Painted Desert in South Australia in A Woman of the Future. It is dusk, but instead of the ubiquitous Australian rusts and reds the scene is drenched in a violet science fiction hue. A man enters the frame from behind the protagonist, revealing that the woman is not alone. They grasp hands and awkwardly spin – the movement is shot from the man’s perspective. The camera falls to the ground (perhaps, along with the man?) and she walks away. Consandine has said that the isolation found in the desert landscape speaks to “a kind of longing” that can’t be pinpointed, and these spaces become overlaid with anxiety. In this video work, isolation, longing and a sense of unease knot around each other to uncomfortable ends.

A Woman of the Future was exhibited in 2016 as part of The Wandering Eye/I at the Centre of Contemporary Photography, curated by Consandine. Included were works by Brook Andrew and Stephen Garrett whose shared approach to landscape was described by former CCP director Naomi Cass as anxiously questioning cultural identity. One reading of the work could be that the sense of longing encountered here is the search for a sense of national place, and the anxiety of being on stolen land.

However, in this presentation the agitated and ambiguous state speaks of something buried deeper that can’t be readily identified. Longing is desire, and to desire is to yearn for something, but here the object is unclear. This feeling was present in the rest of the works in the exhibition. The purple sunset in the video was reflected in the purple paint on discrete walls of the gallery. The disembodied sculptural heads in polished cast bronze were covered with white patina but the weight associated with traditional sculpture – commemorative and designed for longevity – was usurped by their fractured nature and placement on the wall. They gave the impression of falling, positioned upside down with their crowns touching the wall. Like the video, there was a mix of the commonplace and traditional – the landscape as subject and the classical nature of sculpture, but the pervading mood was very much contemporary and apprehensive. There was also a faint gothic undercurrent to the exhibition. This was heightened by the historic architecture of the gallery with its three rooms coming off a hallway, which recalled gothic novels where labyrinthine rooms add to psychological tension.

Her/e spoke of unsettled movement between a sense of self and place, the focus shifted from the landscape to the female protagonist and back again. This repositioning occurred not only within the works themselves but also across each other in the exhibition, from film to sculpture, to installation, creating an evocative exhibition that haunted.

Her/e was at Sarah Scout Presents, Melbourne from 8 June to 7 July.

This article originally appeared in the September/October print issue of Art Guide Australia.