Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

In 2015, Sydney-based artist Caroline Rothwell undertook a residency at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, United Kingdom. While there, she had access to the original colour plates used to create Joseph Banks’s Florilegium, an illustrated document of botanical specimens collected during Captain Cook’s voyages around the Pacific, from 1768 to 1771. Systematically gathering thousands of specimens, Banks eventually took botanicals from Kamay/Botany Bay, the site of first contact between Europeans and the traditional owners of the Dharawal nation.

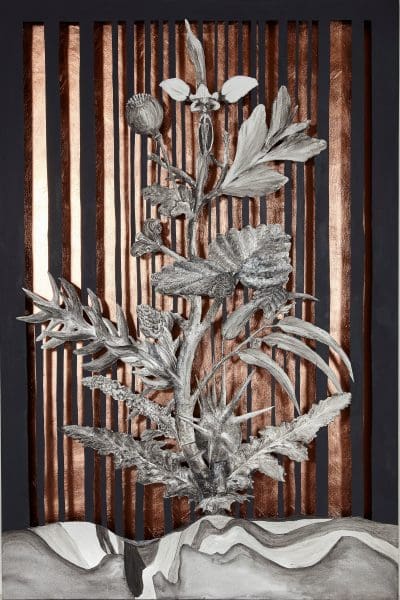

Using a set of prints from Banks’s Florilegium as a conceptual springboard, Rothwell has created Horizon, an exhibition of sculpture, drawing and animation. It explores the increasingly entangled connection between humans and nature. Taking a visual cue from the landscape around Sydney’s Hazelhurst Gallery, much of Horizon was conceived during walks Rothwell took through the Kurnell National Park, located within the Kamay Botany Bay National Park.

In visiting the places Banks would have traversed, Rothwell noted what had changed from the late 1700s to now. “I went to these areas at the same time of year and found some of the plants flowering a little earlier,” she says. “I noted things that weren’t present, as much as things that were. Horizon is about looking back at the archives but also thinking about generative forces, whether they are positive or negative.” Reflecting these natural and human-imposed changes, in Horizon Rothwell has subtly doctored images from Banks’s Florilegium. Each doctored plant sprouts a delicate pink tongue curling around its blooms and leaves. Cutting through Banks’s finely rendered illustrations with a scalpel blade, Rothwell inserted her watercoloured tongues through the paper to appear as though they were part of the original image. Referring to this technique as splicing, Rothwell says, “The tongues look quite snake-like and consuming. I like the double edge of these perfect prints and these quite abject forms; they grow into something else.”

Rothwell’s tongues also appear in a series of orchid-like sculptures—brightly coloured, spindly arrangements that look like they stem from science fiction, but partly centre on colonisation. “The complex thing about Florilegium is that the specimens are so epically rendered and so beautiful, yet they are also symbols of colonial invasion. Something so potentially benign can end up being so political.”

This way of thinking flows through to Rothwell’s use of carbon emissions as a drawing material. Comprised of fossil fuel by-products, Rothwell mixes blackened dust with binder to create an ink reminiscent of Lamp Black, an ink derived from lamp soot commonly used in the Victorian era. For Horizon, Rothwell has animated her emission drawings into moving filigrees and decorative steampunk machinations. Similar to her animation Carbon Emission 5, Constructivist Rococo, recently included in The National 2021 at the Museum of Contemporary Art, in Horizon viewers must look through a peephole in a doorway to see the animation unfold. “Because I come from a sculptural background, I’m always thinking about the body, the human relationship to architectural scale, of how we relate to work in a space,” Rothwell explains. “When you are looking through this peephole with just your eye and the animation’s eye, it’s an intimate connection. A doorway is like a portal into the home and the mind, it’s a very personal space.”

Rothwell has used carbon emissions as a material prior to Horizon, and much of her recent work has been spurred on by residencies undertaken in the past seven years. In 2014 Rothwell undertook a residency in upstate New York and was consequently invited in 2015 to create a work for Temple Contemporary at Temple University in Philadelphia— and it was there her experimentations with fossil fuel emissions took a pivotal turn. Bringing attention to endangered species, Rothwell used soot collected from Temple University’s smoke stack to paint huge murals of plants on the side of the Temple Montgomery Garage. Over time the images faded. In a poetic conglomeration of beauty and toxicity, Rothwell’s carbon emission drawings speak to the inherently political nature of her imagery and how it communicates beyond just the visual.

Most recently, Rothwell has been collaborating with Google Creative Labs on Infinite Herbarium—an app-based archive of futuristic hybrid plants derived from images contained within the open source Biodiversity Heritage Library. Combining human interaction, multi-channel projections, and scientific illustration data, users are able to morph two plants together to create a new species within seconds.

Again, touching on the idea of collecting and categorising, for Rothwell this process fills in the gaps of history and illustrates a potential future. “With archives I’m always fascinated by what is left out. An archive is always written from a particular perspective—Indigenous stories and women’s stories get left out. I’m interested in reclaiming these botanical worlds.”

A contrast to the delicate botanicals seen in Banks’s Florilegium, the specimens in Infinite Herbarium are projected at human scale, their undulating forms taking on the appearance of lungs, hearts and limbs. “At such a huge scale, the plants become very bodily. I want these forms to be bigger than us so it’s not us imposing, it’s them imposing on us.”

Horizon

Hazelhurst Regional Gallery

26 June—5 September*

The National 2021: New Australian Art

Museum of Contemporary Art

26 March—22 August*

*Please note due to COVID-19 restrictions in Sydney, the Museum of Contemporary Art and Hazelhurst Regional Gallery are currently closed. Exhibition dates may also change. Please refer to the gallery websites for reopening dates.

Bloom Lab

Caroline Rothwell

Tolarno Galleries

4 September—2 October**

**Please note due to COVID-19 restrictions in Melbourne, Tolarno Galleries is currently closed. Exhibition dates may also change. Please refer to the gallery website for reopening dates.

This article was originally published in the July/August 2021 print edition of Art Guide Australia.