Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello’s Glass Acts

Telstra National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards 2025 finalist Jennifer Kemarre Martiniello has spent decades crafting an art practice that weaves together memory, heritage and form.

Reflecting on Carol Jerrems’ work has me thinking of matrilineal lines of artistic enquiry, mentors, and the complex relationship between portraits and truth-telling. My research led me to the Rare Book Room at the State Library of Victoria for A Book About Australian Women; to a discussion with the director of curatorial and collection at the National Portrait Gallery, Isobel Parker Philip, about the impetus behind Carol Jerrems: Portraits; to conversations with contemporary photographers Anu Kumar, Ying Ang and Katrin Koenning; to considerations of the triumphs and gaps in feminist thinking of the 1970s. In a landscape where we are continually redefining the needs, structures and permutations of feminism (and of writing and photography), we must consistently challenge our understandings by both looking at the past and considering the needs of the future. This intention exemplifies Jerrems’ legacy—a practice that continues to spark current photographic discourse.

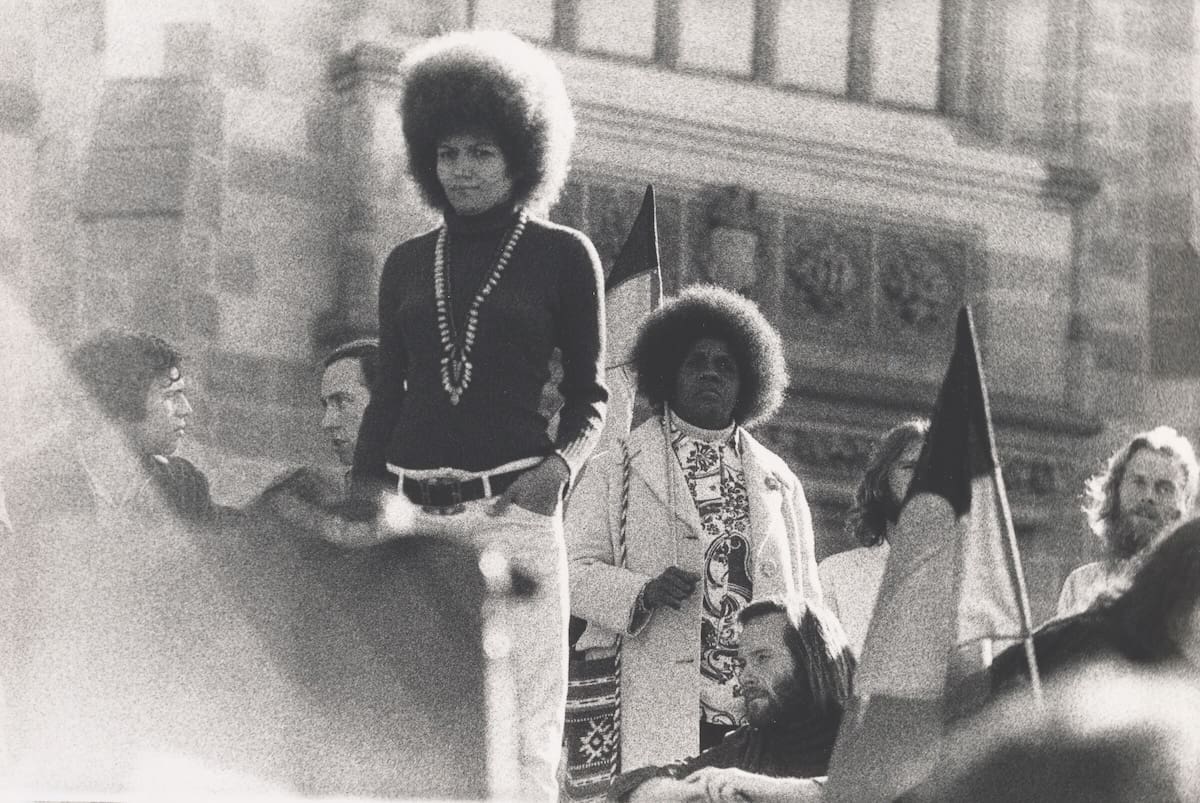

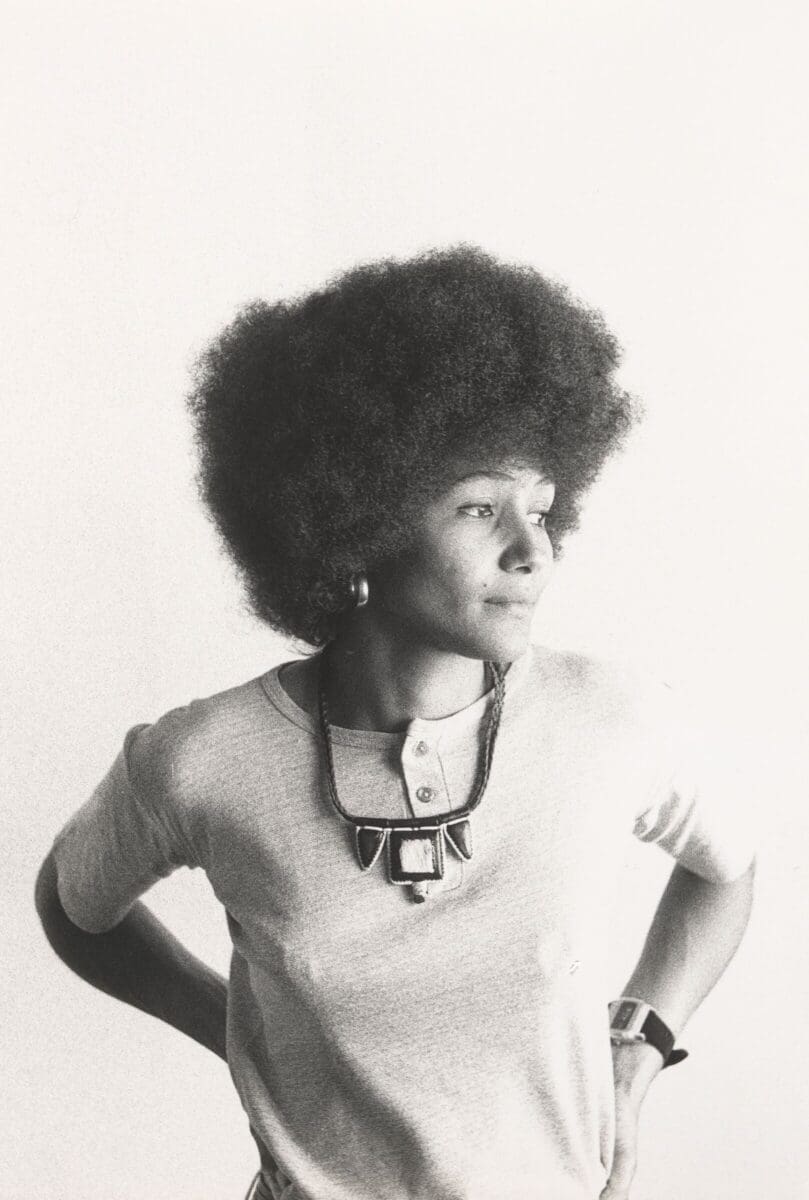

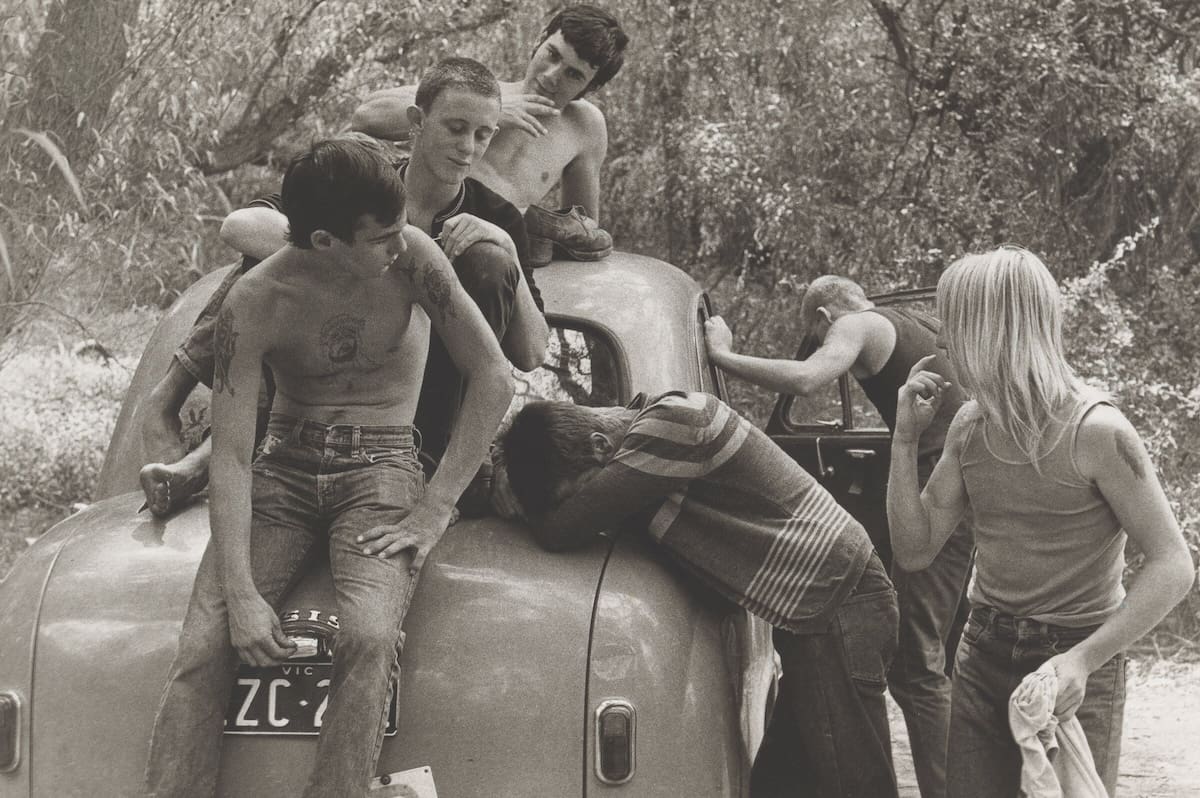

Carol Jerrems: Portraits celebrates Jerrems’s oeuvre, one that charts 1970s social change through feminism, First Nations activism, youth subcultures, and art. The exhibition was inspired by and coincides with the 50th anniversary of A Book About Australian Women by Jerrems and Virginia Fraser, originally published by Outback Press. Parker sees the book as a “chronicle of the era’s cultural moments and reflection of the profound intimacy, care and tenderness of Jerrems’ work—encapsulated in the soft glances between subject and photographer”. The book showcases Jerrems’ portraits of diverse Australian women, coupled with texts edited by Fraser. In Parker’s words, “[Jerrems and Fraser’s] contributions operate on different planes, but they are pushing at the same approach—this is not meant to be comprehensive.” They speak to the plurality and multiplicity of female experience. We know writing and photography cannot be comprehensive—it’s this openness that allows them to be apt vehicles for the in-flux challenges of feminism. Recognising that a continuum of feminist voice is important for action, Jerrems looked to her peers as experienced mentors and agents of progress. We look to Jerrems, and the writers that travelled aside her, to ascertain where to go next.

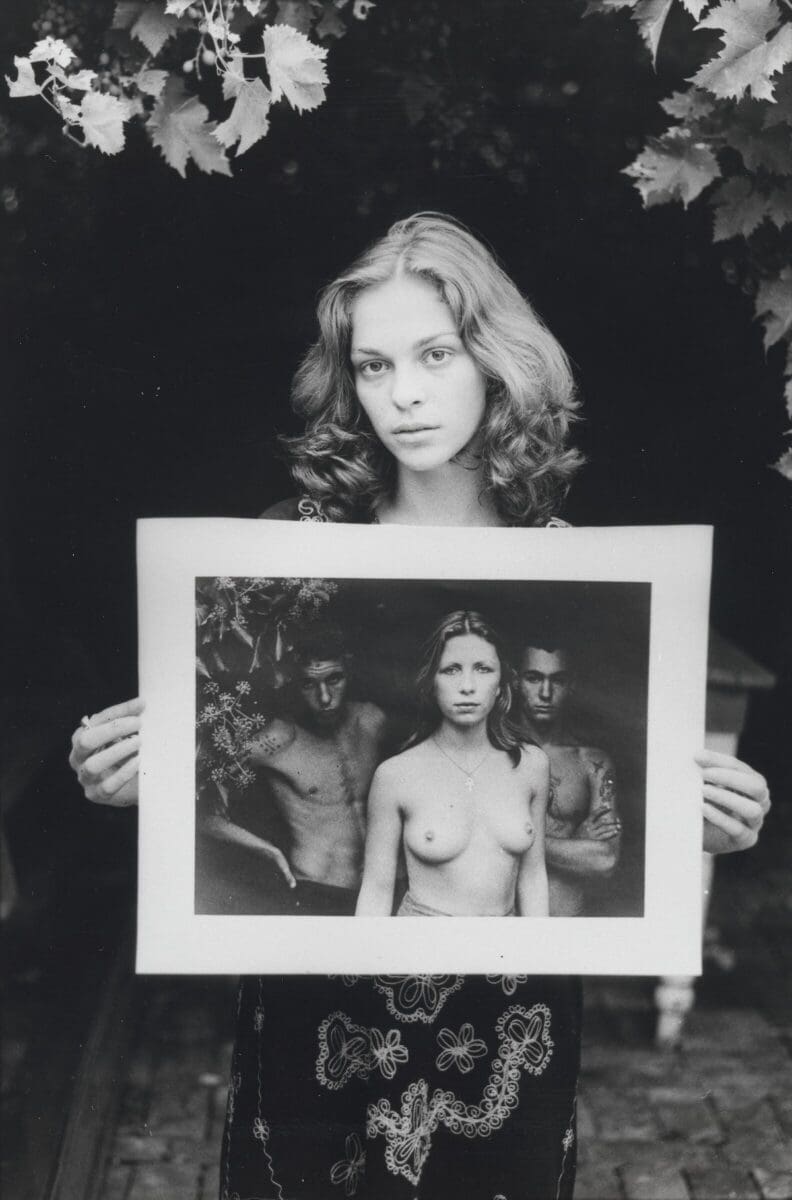

A key photograph in the book is the portrait of writer Anne Summers, taken as she was finishing her 1975 classic Damned Whores and God’s Police. It imagines the anxiety accompanying the final stages of writing. Summers reflects, “I was afraid I was not up to the task […] which was nothing less than to rewrite our history.” This book is an important tome towards the progression of Australian feminism. It sought to dismantle the prominence of the ‘nuclear family’, acknowledge the realities of domestic violence, and spoke of the economic disparities between men and women. It also reflects the gaps in feminist thinking of the time. There is a complete lack of awareness of the need for space for non-binary / gender-fluid individuals under the umbrella of feminism, and a lack of the acknowledgement of different racial experiences of feminism. We know that issues faced by First Nations and POC women at the hands of the patriarchy are usually coupled with additional discriminations than that experienced by white women. The book provides a snapshot of Summers’ experience that led others to challenge normative thought. Summers’ snapshot has been built upon, as more diverse voices have been welcomed and as our vocabularies have expanded. Reflecting on the importance of intergenerational exchange, I decided to read the most recent printing of the book non-chronologically—I flicked forward and read the initial book of 1974, before returning to the beginning to read successive introductions written for reprints published in 1994, 1995, 2002 and 2016. I finished with the initial introduction from 1974.

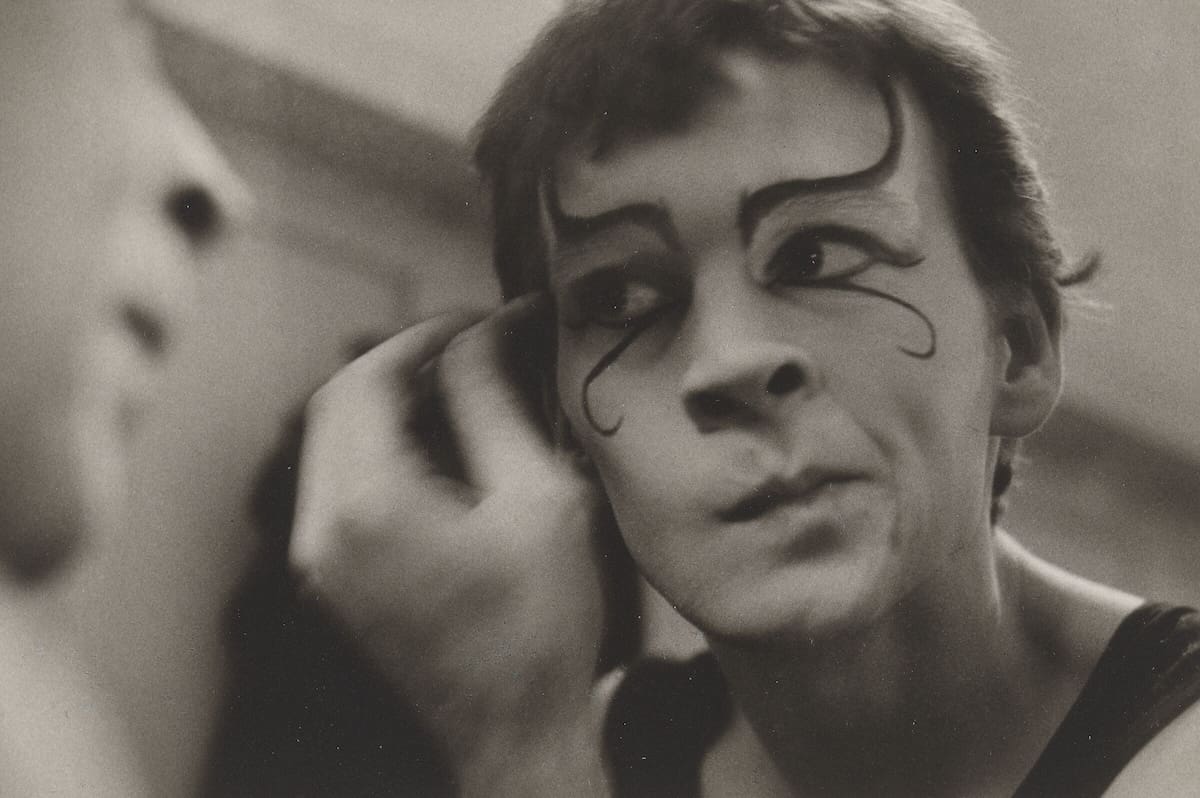

Through Jerrems’ photographs we look to the past to understand the present. Summers recounts, “in order to start devising serious strategies for liberation in our own time, a more precise understanding of that place and time was necessary. […] Because our history was rarely written, or failed to be absorbed into the mainstream […] each new wave of activities has almost always had to begin all over again.” Summers writes with self-transparency– something many of her literary predecessors couldn’t do, often needing to conceal their gender to be published. With each move towards transparent understandings of our progress, failures and challenges, we become individually more acquainted with our true selves. Jerrems’ magic lies in her ability to create a comfort and trust with her subjects. Parker notes, “her work is candid, not set in a studio […] but there is always an element of choreography. She is attentive to how images can be gestures of honest storytelling.” Jerrems’ oeuvre provides reflections of diverse women, presented without hierarchy—predecessors to the force of Australian women since, that have contributed to feminism on their own terms.

It’s no coincidence that NPG has staged a concurrent exhibition, if only we could take the time: contemporary Australian photography, featuring three current female photographers: Ying Ang, Katrin Koenning and Anu Kumar. As Parker explains, “when you see their work, you appreciate how Jerrems’s legacy is still present and informing how we think about photography.” They echo Jerrems’ feminist underpinnings as they speak to their own experiences, while gesturing to legacies from the past. When speaking of the relationship between feminism and practice, Koenning acknowledges, “a good mentor can be like a compass” and wonders, “if any creative act performed by a woman is inherently an act of resistance?” Ang understands that mentors, “show us possible ways forward, by illuminating the ways forged through the past” and sees her work as “feminist practice by virtue of the black hole of female-led stories and experiences in art history.” It was Indian photographer Dayanita Singh who encouraged Kumar to “continue to tell the story” of her Indian heritage. Meeting the same challenge faced by Jerrems, Kumar notes, “my aim is to be able to take a portrait. It’s a very complex art, to be able to truly capture someone in an image. My grandmother never got the opportunity to work. My mother became a doctor, but didn’t have the opportunity to pursue art. I—the third generation—have the privilege of pursuing a career as an artist. I don’t take this lightly—it is a feminist act to be making work.”

As I end my research with the initial 1974 introduction Summers wrote for Damned Whores and God’s Police, I find her reflection on the portrait that led me to this book: “in 1974 Carol Jerrems photographed me. She was just starting to make her mark […] and I was struggling to finish this book. Six years later, Carol died aged just 30. Most of her portfolio was portraits of women, young and old, most of them not well known, many of them, like me, just starting out. Carol caught something in me that day. I look ruminative, brooding, slightly sceptical. It’s as if I am wondering where this whole women thing is going to end up. I still am…”

Carol Jerrems: Portraits

National Portrait Gallery

On now—2 March

This article was originally published in the January/February 2025 print issue of Art Guide Australia.