Place-driven Practice

Running for just two weeks across various locations in greater Walyalup, the Fremantle Biennale: Sanctuary, seeks to invite artists and audiences to engage with the built, natural and historic environment of the region.

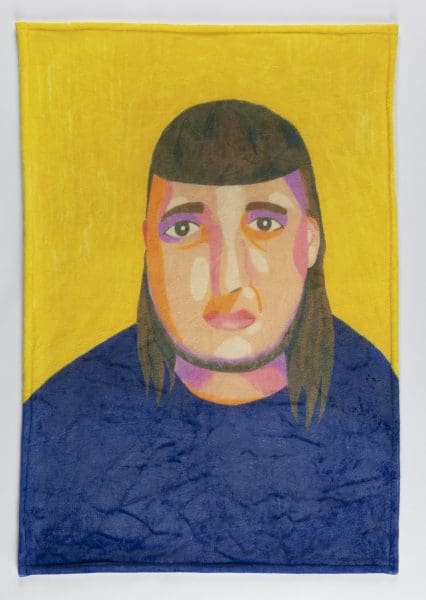

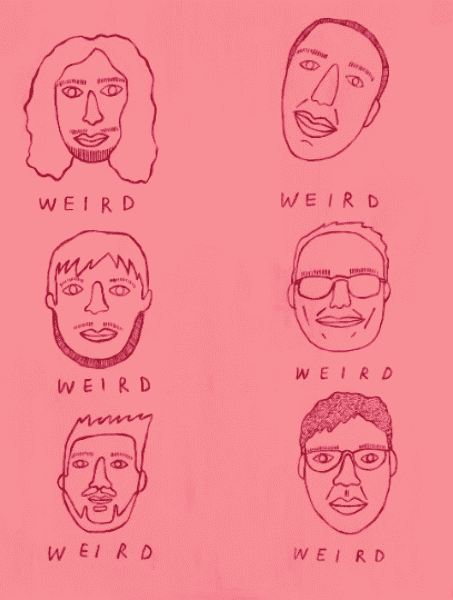

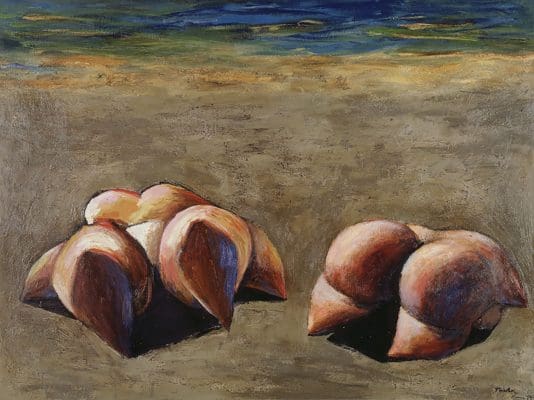

We all like to people-watch, but in the hands of Perth-based artist Carla Adams the study of Homo sapiens takes on a proto-scientific rigour and scale that approaches substantive data. The artist’s droll assessments of online dating culture draw on her extensive observation of platforms like Tinder and eHarmony. Her study of opening lines and profile pictures reveal trends in the way people represent themselves online, brook interactions with strangers, bid for attention and negotiate gender. In sorry I was/am too much, Adams presents her work alongside a selection of Albert Tucker’s paintings and drawings from the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA) collection. The artist spoke to Sheridan Hart about the complexities of this cross-historical pairing, exhibiting in a state gallery, and of course, the colour pink.

Sheridan Hart: The title for this show is an apology. Where did it come from?

Carla Adams: It’s from my visual diary, [AGWA curator] Robert Cook picked it out. It seemed to encapsulate something about the way people are made to feel that they take up too much time or space. I think women, especially, can relate to feeling too smart, funny or needy. There is also a nod to that millennial mood of celebrating being a mess.

SH: How did you approach the artist/curator relationship?

CA: At first it felt weird that anybody would be interested. This is not just humility: I know how the trick is done. I sit in the studio talking to guys online, so the magic of the final work is demystified for me.

Robert Cook wrote a beautiful essay and when I read it I had this overwhelming feeling and was crying. To have someone, especially a man, get such personal, feminism-centred work, was so exciting. This has been a great opportunity for me to reach a wider audience.

SH: You are a prolific, forward-looking exhibitor. This show has retrospective elements: what has it been like to look back?

CA: There’s this feeling that when an exhibition ends, the work becomes old work and you can’t show it again. I think lots of artists feel it, especially if you’re not a very commercial artist. Seeing my work all together has reiterated a kind of ‘big three’ for me. If it’s funny, has a strong title and a good story behind it; then it feels finished, like it’s doing its job.

SH: You are running public workshops for the exhibition. How has it been to meet your audience?

CA: It has been fascinating. I’ve noticed even young people have been echoing the show’s critical take on Tinder. A drawing titled Men who have been mean to me on tinder has been reposted several times. Perhaps people relate to what it’s like to be a woman using online dating, or to reclaim some of those negative feelings. Coming up, I’m giving an artist’s talk, hosting a singles’ Valentine’s Day workshop and doing a reading of my work 1000 Tinder Opening Lines.

SH: Has any feedback surprised you?

CA: The ABC posted an article about the show which quickly got over 90 comments. They were all so funny. Some people said my work was misandrist, others discussed internet privacy.

Interestingly, it is always men who have a problem with privacy in my work. One of them called me deplorable, for taking ‘these poor men’s’ profiles and making them public. While it’s never my intention to make fun or be cruel, the profiles were already public, populated by the users themselves. For my work Describe Yourself in One Word, I asked 1000 male Tinder users to describe themselves. Some I told about the project, others I didn’t.

The ABC discussion made me think about how attacked people feel when they go outside their bubble and interact with non-like-minded people.

SH: Your method involves collecting hundreds of interactions from online dating. What drives this volume of research?

CA: At the heart of me there’s a detective who needs to gather all the data. It also comes from the fact that people have emotional reactions to my work. I get a lot of ‘Not all men…’ or ‘That’s not my experience…’ And maybe subconsciously I’ve found a way to reply with data. I mean, 69 men said ‘horny’ for their one-word descriptor. The numbers don’t lie.

SH: Cook placed your work alongside that of Albert Tucker (1914-1999), an Australian modernist icon. How did that strike you?

CA: It seemed strange at first, but when I saw his works up close (for example his painting of fleshy, bathing women), it made sense from a material perspective. Put his drawings beside my visual diaries and there are interesting similarities. The immediacy of marks, interpretation of figures.

Somebody asked me if Tucker would like the show. I wondered about that. I employed an internet psychic to ask Tucker’s ghost. The answer was wishy-washy. Obviously.

Ultimately, I think he would not like it. His pain, his views on women, these things mean he wouldn’t understand it as we do. I also think maybe that doesn’t matter. I do feel a closeness to him, though. When I see his work, I think ‘Oh, there’s my mate Albert.’ I sympathise with his experience of emoting and processing trauma through art.

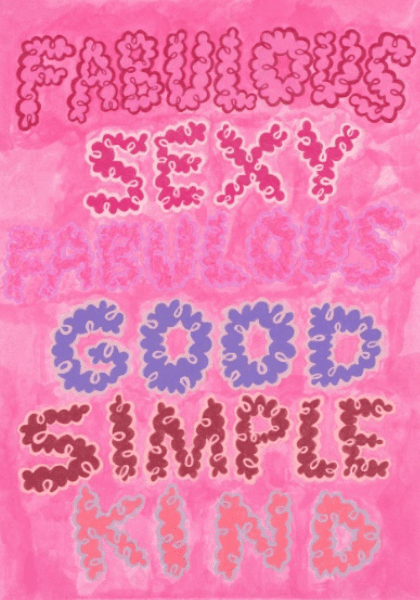

SH: When I first saw your name billed alongside Tucker’s, I found myself scanning his work for pink, which you use liberally. What’s your relationship with pink?

CA: I used to hate pink. I’m a goth at heart. So it just wasn’t on the cards, style-wise. Now, I can’t get enough. In this exhibition, the walls are pink.

In 2016, the Pantone colour of the year was Rose Quartz, also known as millennial pink. It became such a trend for fashion, homewares, technology, devices; everything was that soft, baby pink. So much so that it has become a neutral. If you go to Kmart to buy a cushion, they will come in black, cream and pink, as though pink is nothing now, like white. Pink will live on. Mark my words.

sorry I was/am too much

Carla Adams and Albert Tucker

Art Gallery of Western Australia

12 December – 15 March 2021