Material curiosities: Primavera 2025

In its 34th year, Primavera—the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia’s annual survey of Australian artists 35 and under—might be about to age out of itself, but with age it seems, comes wisdom and perspective.

For over 40 years, Julie Rrap’s work has been animated by a paradoxical force: that throughout art history, women’s bodies are a ubiquitous motif—but only as objects, narrowly reduced to a set of predictable conventions. Her photography punctures and defangs the dull tropes produced by a male artist observing an idealised female sitter, making an argument against ideals and asserting that women live in messy, fine, imperfect bodies, the variety of which have rarely been shown in art.

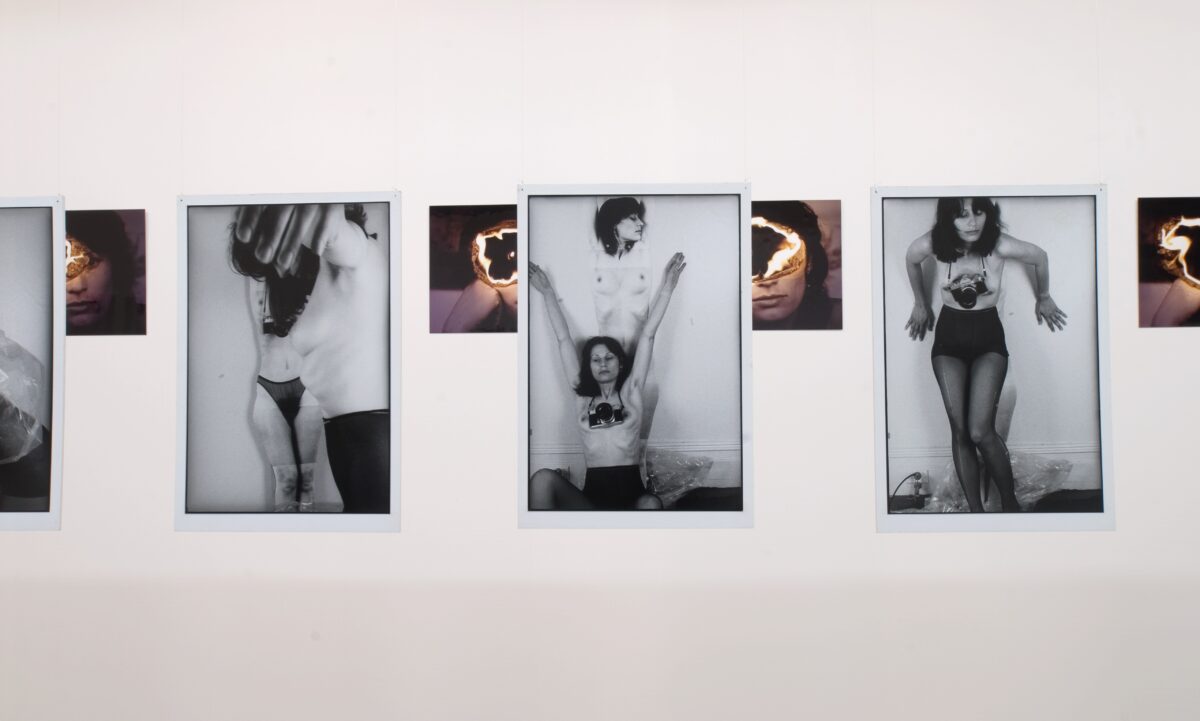

The work that brought Rrap to notice was Disclosures: A Photographic Construct, an installation in the Museum of Contemporary Art’s (MCA) collection, in which Rrap plays the role of photographer and model, showing the visual viewpoints of both sides. The work was made in 1982, when the term ‘the male gaze’ was barely a decade old. In it, she asks: can the nude become the artist? Can women artists contest how the female body has been shown throughout art history?

Rrap’s current survey Past Continuous at the MCA exhibits Disclosures with newer works that consider the cultural invisibility of the ageing female body. It amounts to a personal counter-canon that blocks the male gaze and is key to the story of feminist art on this continent.

Lauren Carroll Harris: Would you say that ageing is among the least visible, least accepted margins of not just art but of feminist art?

Julie Rrap: When I did Disclosures, it wasn’t well accepted among feminists. Subsequently, things moved on and feminists realised that you can use a naked, younger female body to critique how it’s used more broadly. But it was strange that there was quite a reaction against what I’d done. So how would they think of me now using my older body?

I would imagine there would be more empathy to the ageing female body now. In Disclosures, I was challenging the overexposure of young women’s bodies. But the naked older female body isn’t really represented anywhere very much, not even in art history. And when it has been, even portraits of older women’s faces, they’re not even associated with the wisdom of age, but more with old crones and witches. I’m interested in not just how we might think of that type of body as attractive or not, but also the idea of vulnerability. I don’t want people to think “I feel sorry for that old dear.” It’s to show strength in the older body. As soon as you get older you are immediately associated with being disabled in some form or another just because you’re old.

So I’m trying to get a balance between vulnerability and strength, with defiance in the face of getting older, and how that sits with a society that hasn’t been very receptive to that, and if you had to put it under registers of beauty or ugliness or the grotesque, it would probably not fall under the conventions of beauty. I hope it is thought-provoking: that the notion of a younger and female body is so associated with beauty that it is a form of conformity. It’s the way we’ve all been trained to think and there are histories of that to back it up.

LCH: Do you think there’s something distorted about the cultural discussion about women artists today? That it’s so anchored in exceptionalism, careerism, individualism, status and the rhetoric of greatness?

JR: Where we now talk about the marginalisation and invisibility of women artists through history, the exact same marginalisation and invisibility happens in other ways too: if you’re beyond the centralised cultures in Europe or America. It’s so interesting that people don’t reflect on their own habits of marginalisation. Often they only discuss the women artists from the same places. It’s very annoying as an Australian woman artist. Marginalisation comes in many forms, including that of other places.

LCH: There remains the dichotomy of the European metropole and the distant colony, or just the Anglophone world. And the elite, mythical rhetoric of greatness and artistic genius stays intact.

JR: You have to play to that tune. It’s hard to shrug off those old hierarchies of thought. The terminology is always still within that idea of the genius. Do we have to always position women artists as matching up to the male genius in that way? There’s so much myth-making.

LCH: In Australia, has one of the hierarchies been to privilege those making work relating to Australian national identity? Prizes, surveys and big exhibitions often prefer themes concerning Australia. Your work has never trafficked in those tropes.

JR: When I started out, I saw feminism as an international movement. I just always thought I made art in the world. There’s a narrowing of what can be Australian art and it’s wrong. In some ways, that’s why Australian art hasn’t been taken up more [overseas], because it’s placed within such a narrow vision. We all get boxed in by it.

LCH: A lot of artists of your generation embraced that national lens. But you didn’t. Your work has formal concerns. Why do you think form isn’t more valid for a discussion point?

JR: It doesn’t mean that you can’t work with that [national] lens, but it’s not the only lens. It’s limiting. Or there was a sense that you had to do landscape. I grew up in the bush. But I always worked with the body.

LCH: After seeing Disclosures exhibited alongside your newer material, I started thinking that part of what makes your whole body of work so interesting is that we see you making art through the passing of all these different waves of feminism, and yet your ideas still retain this currency despite cultural and social upheavals.

JR: Working with the body is such a classic idea. I’ve plugged into a very classical line of thought. The body has always been in art and there’s always been different ways to think about it and visualise it. So because that’s such a strong through line, my art can move through those different phases of time. At the beginning, my work was critiqued through self-conscious feminism. Now, I don’t know how it will be received. And when I have used a body it’s been my own, but you don’t find out much about me in that personal sense. You just see a body moving through time. I also think that this show is as much about time as it is about a body. I show a body through time.

LCH: That’s what we see in your works: a historical body.

JR: By using my body, I’m able to have a conversation with the future. When I made Overstepping with the high-heeled foot, I was going forward in time and wondering what people would change cosmetically. I’m also throwing back in time into the history of art. Art allows you to slide around across time, from centuries ago, to being predictive. You can time travel.

LCH: The word “disclosures” carries a very different contextual meaning now, since the MeToo movement. It became the word of the day in 2017.

JR: I hadn’t thought of that. That work is based on a statement from Susan Sontag’s book On Photography that I was reading at the time. She says that painting constructs and photography discloses. I love that book because it’s quite argumentative. You read it and agree with bits of it because she’s a wonderful writer and then you disagree with parts of her positioning. It was an interesting book to think about when using the camera. Here I was using the term “disclosures” in quite a structural way and now it has this complete other connotation. That’s good, isn’t it?

LCH: In putting this show together, do you now think differently about any of your earlier works? Or do you think that any of your older works resonate differently now in this era?

JR: When we were installing Disclosures, there were a lot of people working on it, different generations, many women. It was shot in just a room in my old crappy terrace house in St Peters, and it was a bit like Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. It’s quite innocent in a way. It’s highly constructed in its form. And playful. The stockings. The cover-up. The tease. But the installers’ observations were very much about social media now and the selfie.

LCH: That’s the other new context. The confessional bedroom is now the stage for the self on social media, the theatre of everyone’s lives. But your self-portraiture has never projected that kind of persona, which is what everyone now has through their branded online selves. Or a confessional lens of shame versus shamelessness.

JR: I knew that in Disclosures I was taking up two positions: my view of the room, and the camera’s view of me. I was playing a game. When you’re being photographed, you’re always looking at something, and the conceit of the work [was to see what the sitter sees]. I was having fun but very clued into how images get constructed and read. I’ve been reading Miranda July’s new novel.

LCH: Which concerns a protagonist’s revulsion at her own ageing body.

JR: And she’s only perimenopausal. She’s only 45. And the book takes place all within one room [like Disclosures]. I like Miranda July’s social media videos. She has that confessional thing, and the sexual thing, and a persona. She’s obviously from a different generation. I really love Rachel Cusk’s work too. She’s right in the hot zone but sitting outside watching.

LCH: All these reference points you mention are literary.

JR: I’m a great reader. I wanted to be a writer. I did a degree in literature.

LCH: But you think through images.

JR: I love reading literature. It feeds your imagination. You can be reading about important things and if someone articulates that in more lateral ways, then I find it a really good learning space. It’s part of my thinking space.

Julie Rrap: Past Continuous

Museum of Contemporary Art Australia

On now—16 February 2025

This article was originally published in the September/October 2024 print edition of Art Guide Australia.