While the school gym has launched many an athletic career, there is perhaps only one art prize that was born among the treadmills and the barbells. Now in its 21st iteration, the Redlands Konica Minolta Art Prize had its genesis in the Redlands high school gym and has emerged as a heavyweight, with a month-long exhibition held each year at the National Art School in Sydney.

This year, former prize winner Callum Morton selected 20 established artists, who in turn nominated 20 emerging artists. The artists vying for the $25,000 established artist Main Award and the $10,000 Emerging Artist Prize included established artists: Daniel von Sturmer, Jon Campbell, Christian Thompson, Agatha Gothe-Snape and Damiano Bertoli; and emerging artists: James Tylor, Pitcha Makin Fellas, Kenny Pittock, Taree Mackenzie and Jamie O’Connell. Diena Georgetti and Kenny Pittock.

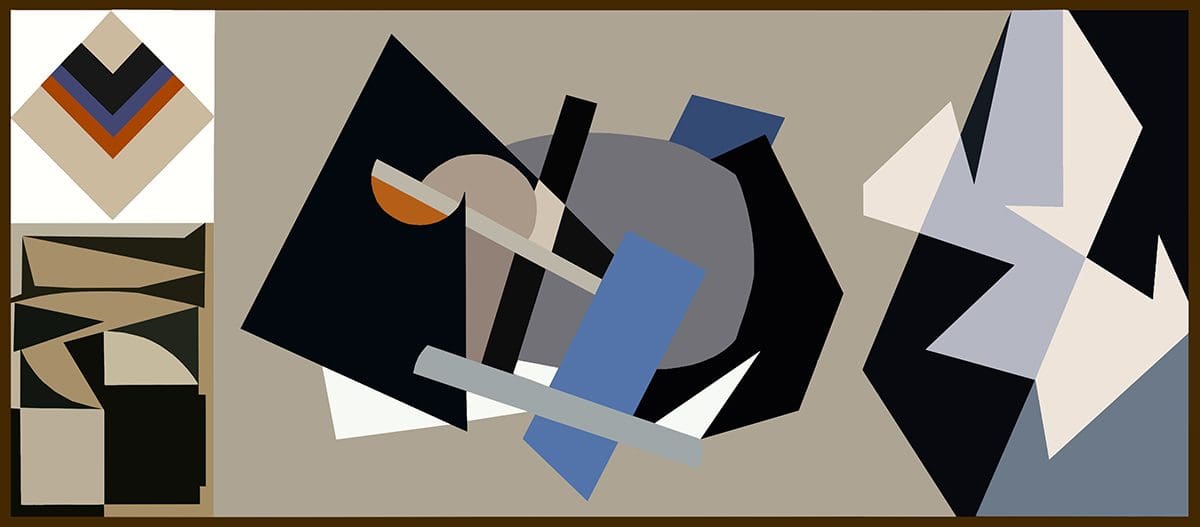

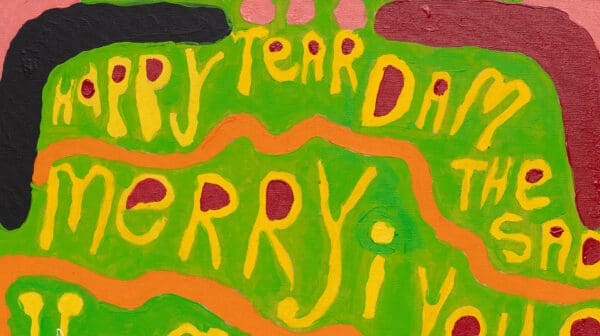

Diena Georgetti was awarded the established category for her work The Humanity of Construction Painting, 2017 and Kenny Pittock was awarded the emerging artist category for his work Fifty-two found shopping lists written by people who need milk, 2016.

Toby Fehily spoke to Morton about the prize and what it reveals about the Australian art world more broadly.

Toby Fehily: What was your process for selecting the artists?

Callum Morton: The first thing I did was make sure I chose artists that had never been included in the prize before. The other thing I did was include collaborative groups, because they hadn’t been included at all in the past. And finally, I was interested in having artists who have a direct connection to that younger generation, whether it’s through teaching, through community, or what have you.

TF: Do you think artist groups or collaborations are underrepresented across the board?

CM: I think the narrative of the market is around the individual artist: it’s easier to sell. Traditionally, people don’t really know how to handle collective artists, unless they’ve been working like that from the beginning and they remain like that. There are a number of collaborative groups I know that also work individually. DAMP is an example, all those artists work individually as well as work collectively.

There is this sort of myopia, I think, in the way we regard that sort of work. Which is not to say we’re blind to it. Museum shows have included a lot of these artist many times. It’s nothing new.

TF: Is there anything you’re hoping to see more of from the emerging artists?

CM: Oh, no. No, no, no. I’m just curious. I’m always curious about what the younger generation is doing. The younger generation can ask very critical questions, particularly early on in their practices, that older generations don’t necessarily do. I think they can teach you a lot about what’s important in the world.

I teach and run the art school at Monash University and it’s always a surprise to see what the students are interested in each year. There is quite a lot of flux in it. Some years they might be super interested in theory and in other years they might be interested in materiality or whatever it is. I’m always very interested to see what they come up with.

TF: What do you think it is that makes this prize so important?

CM: I think what’s important is that it does recognise this continuum across generations, this idea of one generation supporting the next, rather than the Oedipal idea of the avant-garde of each generation replacing the next and killing the former and so on.

And the show is held in an art school, it’s generated from a secondary school, so it’s a lot about education and a lot of education is about that continuum. It’s a very specific prize like that. It has still got all the other stuff to do with prizes: excellent work, a couple of winners, a lot of press, and so on. But I think that structure is very particular and very interesting.

TF: You won the prize in 2013. Have you noticed any changes to the prize or the Australian art world more broadly since then?

CM: The way we’re regarding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture now is quite different. The major state galleries and national galleries for many years have been striving to include the breadth of those cultures in the national dialogue. It has really advanced, and the kind of argument and the complexity of the argument has changed a lot in that time.

If you look at the prize from 1996 through, you can actually trace, to some extent, the way things are moving stylistically, intellectually, what have you, through the Australian art world. This is what is always interesting about prize shows. They’re always going to mark a shift, all the shifts, in the culture, and that’s one of the more recent ones.

TF: What do you have coming up next?

CM: I’ve got a big project in Denmark as part of the European Capital of Culture, in a town called Silkeborg. So I’ve been working on that mostly. I’ve been over a few times because there’s some kinetic work, so there’s a lot of production going on over there at the moment. I’ve got a show at Roslyn Oxley9 coming up this year and I’ve got some public projects too. There’s quite a lot on.

Redlands Konica Minolta Prize 2017

National Art School

28 March — 20 May