Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

This article is written by Joanna Mendelssohn, The University of Melbourne.

A bit over 30 years ago, I met Arthur Boyd, and we talked about art. At the time the Art Gallery of NSW was preparing a huge retrospective exhibition of his life’s work. It was not uncommon for curators and art dealers to call him a “genius”. His response to this adulation was acute embarrassment.

He described his artistic career as “selfish” and saw his own art as ephemeral. The true value of his contribution to Australia, to the world, he said, was in the gift of the 1,000 hectares named Bundanon he and his wife Yvonne were donating to the people of Australia. The Boyds were determined no developer would turn this earthly paradise into real estate.

Arthur Boyd understood the tragedy of loss of place. In the 1960s the much loved Boyd family home, The Grange, Harkaway, had been demolished to become a quarry. His art – and that of generations of his family – had been nourished by its pastoral beauty, which was turned to rubble. Bundanon has been created in the spirit of The Grange, a place for artists and others to create and perform, surrounded by pastoral beauty.

The three separate exhibitions that come together in Tales of Land & Sea, speak to Boyd’s sense of justice, his desire to break down barriers between class and cultures, and his deep love of the ancient myths that still speak to humanity.

The year Arthur and Yvonne Boyd gave Bundanon to the Australian people, 1993, was also the year Arthur Boyd collaborated with a young Indonesian art student, Indra Diegan, on a visual retelling of one of the great West Javanese myths, Sankuriang.

It is a tale of gods who become animals, of love and jealousy, of incest and guilt.

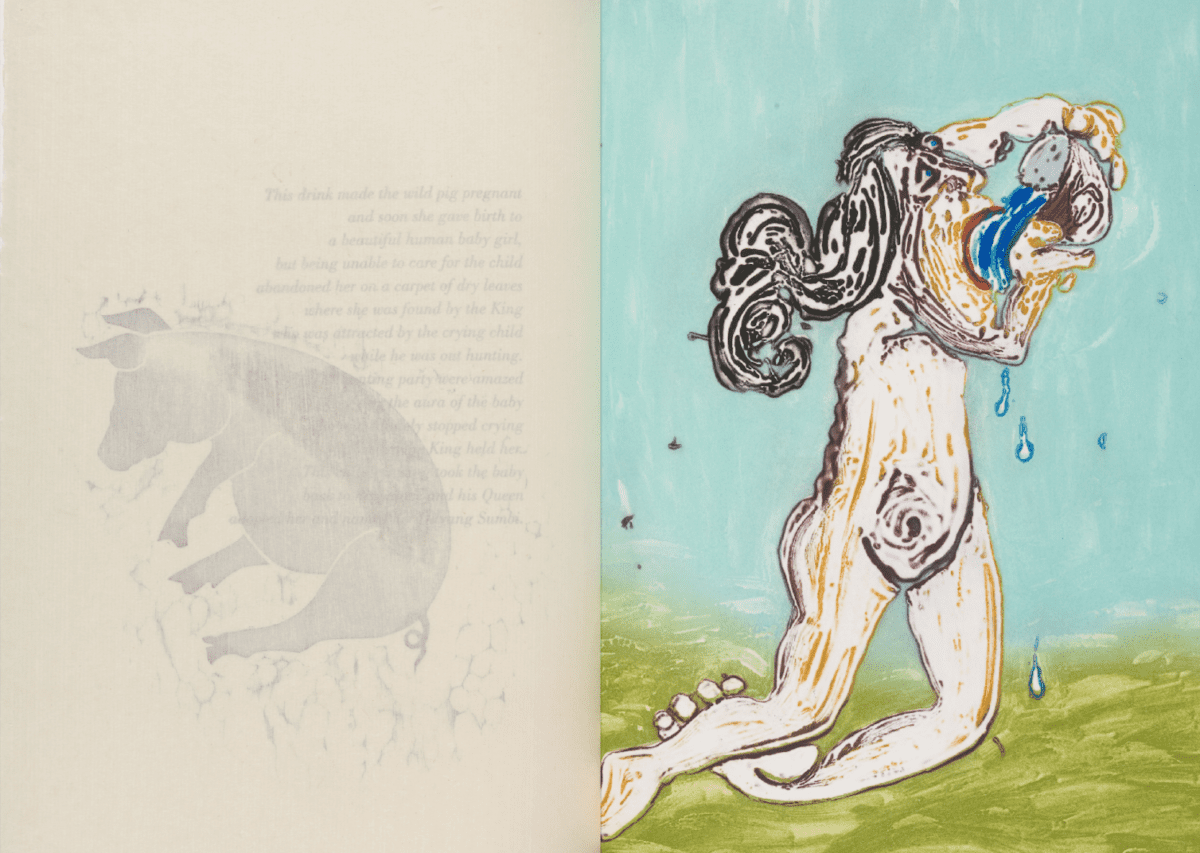

Boyd had been introduced to collotypes, a photographic mode of printmaking, by Diegan’s father some years before, and collaborating on her honours project was a natural outcome of the friendship.

Their final outcome was a book, whose beauty lies in this collaboration. Boyd’s intense, passionate prints work in harmony to create a visual conversation with Diegan’s delicate woodcuts. Only 12 copies were printed. The three in the Bundanon collection form the core of this small, exquisite exhibition.

In the adjoining large gallery is ayang-ayang, showing the work of the artist Jumaadi. Echoes in the form of shadows are at the heart of the exhibition.

In both Indonesia and Australia, colonisation led to mass displacement, exploitation and death. Jumaadi’s paintings draw both on the visual iconography and materials from traditional folk art, a connection emphasised by a separate display of historical Javanese artefacts, including exquisitely carved elaborate hair pieces displayed to throw deep shadows on the gallery wall.

The main exhibition space is dominated by a screening of a performance of wayang Kulit, Indonesian shadow puppetry.

In The Sea is Still a Mystery, a fisherman first catches an abundance of fish, but then his line draws up a bizarre array of sea creatures, a wrecked ship, strange objects (including old beds and a wedding dress) body parts, plants, ships carrying sheep and a head that looks like Captain Cook. The sea may give us life, but it is also the home of the dead.

Some of the subjects and themes in the wayang kulit are repeated and expanded in the paintings and buffalo hide pieces that fill the gallery. These include a series of large works he made during the COVID lockdown. Lovers are shown together, or separated by migration. A large wedding dress has many embryos growing at its base. The artist flies under the wing of a plane across the volcanic islands.

As an artist he can fly free, but the confined passengers may well be indentured labour, facing an uncertain future.

The third exhibition, Sancintya Mohini Simpson’s par-parā / phus-phusā (“to speak incessantly / to whisper”) is an exploration of the legacy of the artist’s maternal ancestors who were Indian indentured labourers, gulled into travelling to South Africa to work on the sugar fields.

Simpson makes the point that the great 19th century migration of Indians to the sugar fields of Africa, Fiji and the West Indies was hardly voluntary. The colonial powers saw them as a substitute for the recently freed slaves, and treated them accordingly.

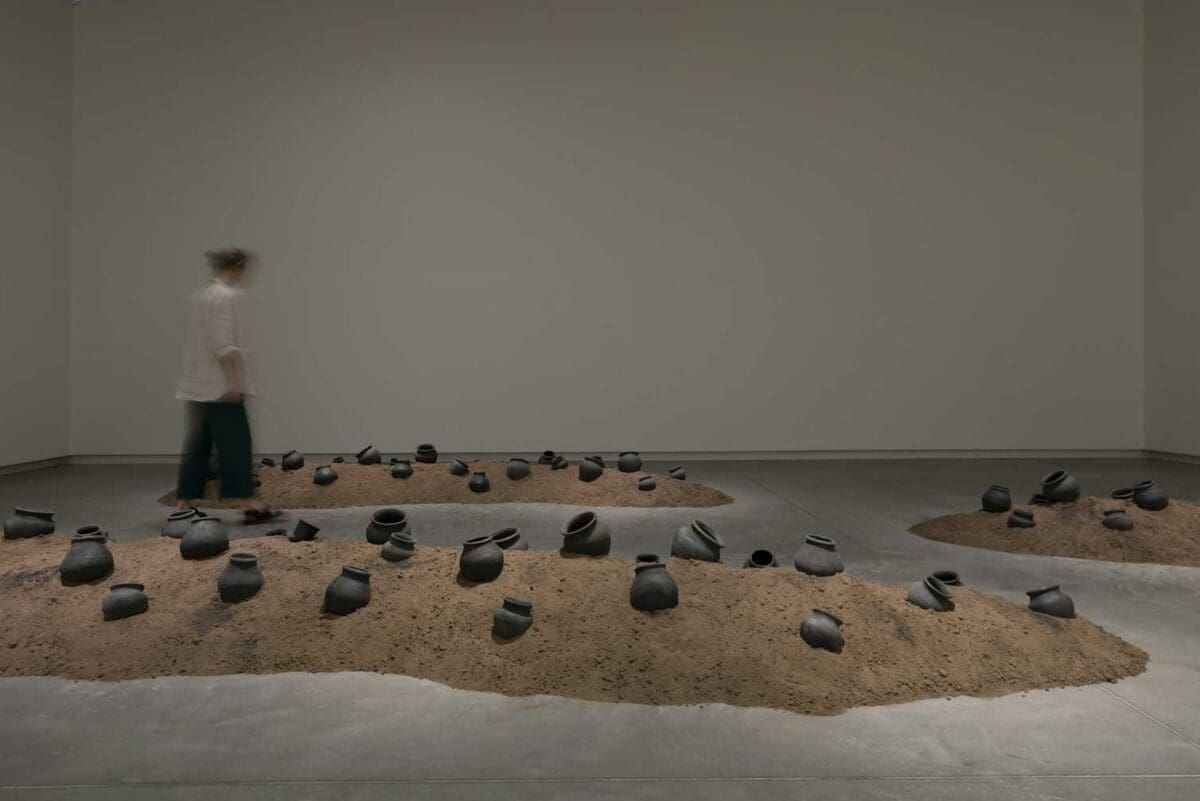

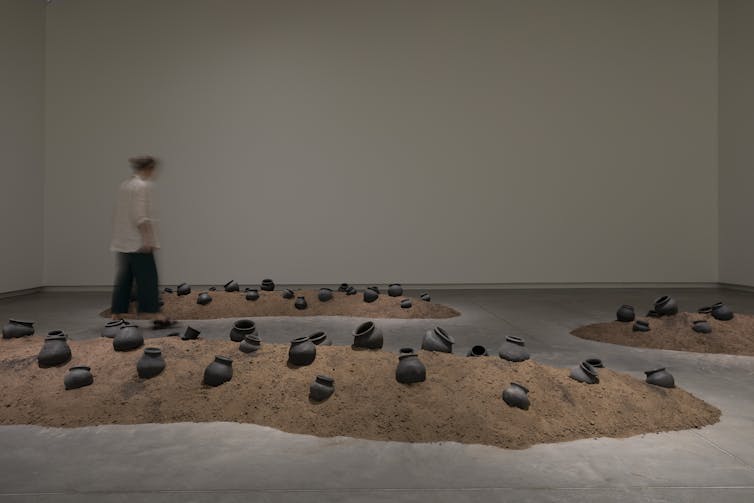

The main installation, Vessel (4) consists of mounds of earth from Bundanon, scattered with ash from caramel-smelling sugar cane. These hold a series of earthenware lotas, vessels used in sacred ceremonies, smeared with sugar cane ash to make them a dull grey.

This is the site for a sound installation piece Simpson performs with her sibling, Isha Ram Das. The lotas vibrate with an amplified sound when gently tapped by both artists in an echoing rhythm.

Their art speaks of labour and loss, of salt for the sea that divided the people from their homelands, and for the tears they shed when they realised they could never return.

As I was looking at the three exhibitions, by artists whose connections to Australia are via different parts of Asia, I thought of Arthur Boyd, and the way his family were also in transit between Australia and England. He knew, as they know, the yearning for the other, the distant ancestral land.

The Boyds’ vision of Bundanon has been fulfilled. Not only has the land been preserved and nourished, but at its heart there is a hub, a meeting place where artists in transit can stop, consider, and create.

Tales of Land and Sea

Bundanon Trust

2 March – 16 June 2024

Joanna Mendelssohn, Honorary (Senior Fellow) School of Culture and Communication University of Melbourne. Editor in Chief, Design and Art of Australia Online, The University of Melbourne

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.