Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

For Gurindji/Malngin/Mudburra artist Brenda L Croft, culture and family always call back and she responds, as an act of survivance. These acts span across archival photography, printmaking and self-portraiture— with Croft working as a visual artist, academic and curator. Her career has moved from curating national exhibitions to the intimacy of poetry— all of which has seen her determined to uncover her family’s legacy, as evidence of their ongoing sovereignty.

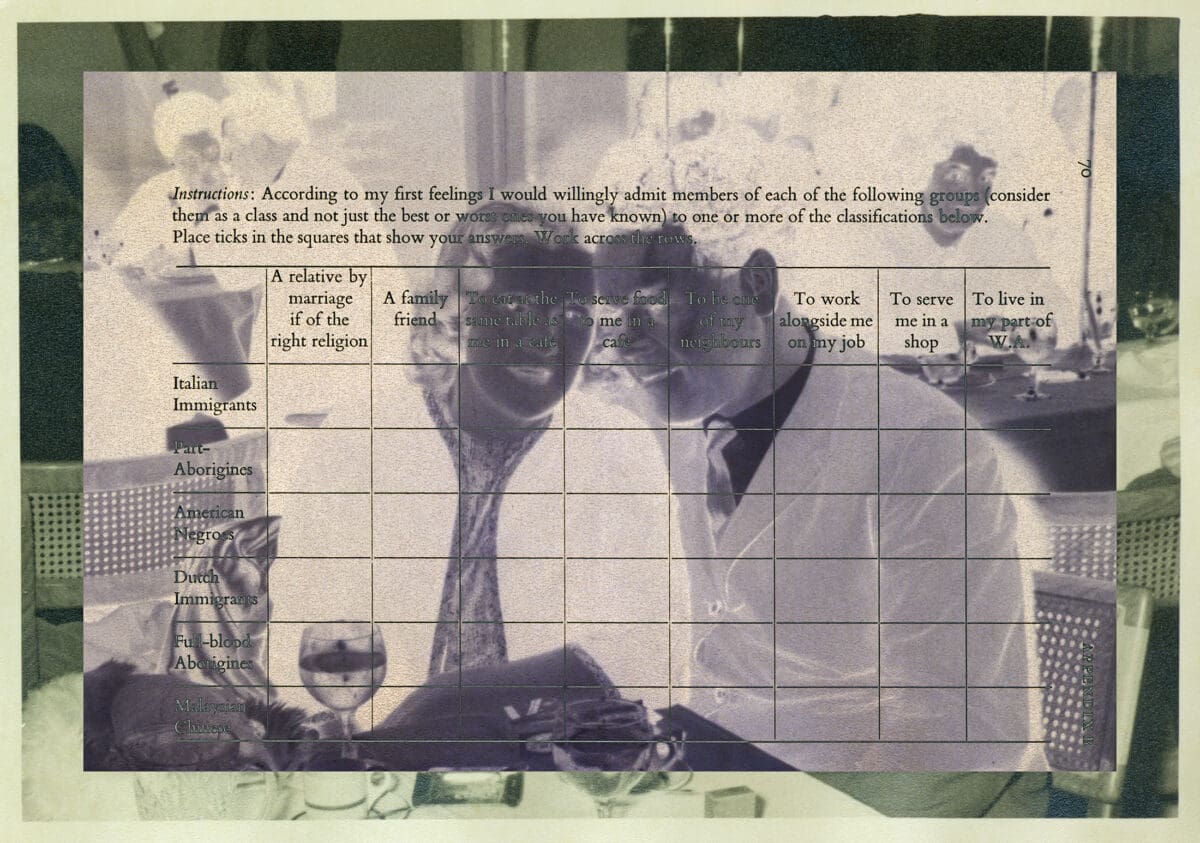

In her 2015 photo essay/poem SHUT/MOUTH/SCREAM she writes, “my mouth’ (tintype) is my silent shut-mouth scream to my grandmother over the decades.” The work uses archival photographic medical records of Croft’s grandmother’s mouth, from when she was studied by a doctor in the 1930s—and later had her son (Croft’s father) forcibly removed from her.

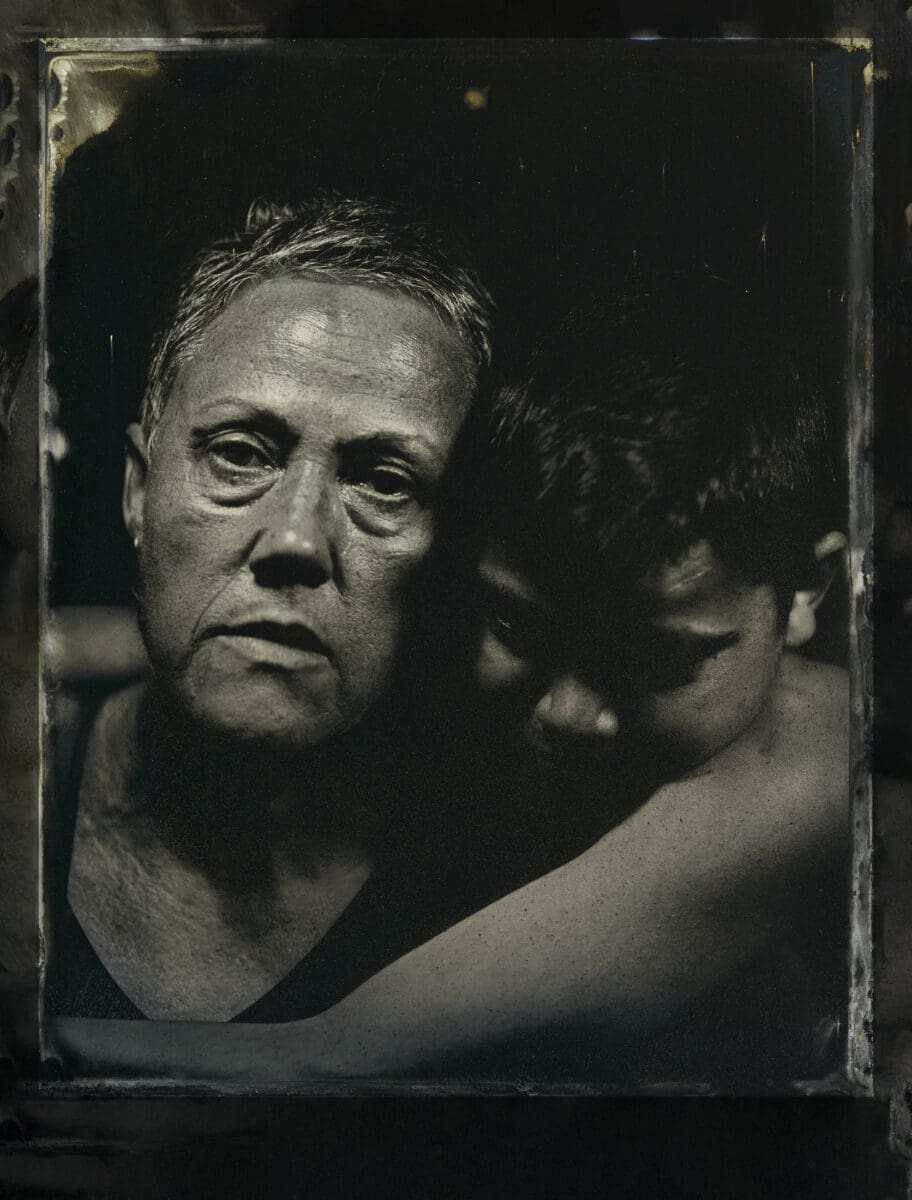

In many ways the work foreshadows Croft’s formidable return to art making, recently winning the ‘Work on Paper’ award at the 2023 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (NATSIAAs) for blood/memory: Brenda & Christopher II. Like SHUT/ MOUTH/SCREAM, this newer piece also illustrates how colonisation not only ruptured communities but became a binding force. In the portrait her son/nephew, Christopher, continues their blood/ kinship despite sharing a non-Indigenous ancestor, reinforcing that blood and culture isn’t diluted when mixed. It’s a parallel acknowledgement that while Croft’s father was taken from his mother, blood memories remain and reconnect communities.

The power of such work resonates in the aftermath of the referendum where uncertainty occupies our consciousness. It embodies the wider cultural resistance of First Nations artists who overshadow government agendas and conservative politics, bringing action and change in other ways. Croft is a leading force within this ever-growing movement, creating a body of work that fortifies ancestors’ past while building cultural pathways for future generations.

Her career evolved quickly when she moved to Sydney from Canberra to study a Bachelor of Visual Arts (Photography) at Sydney College of Arts in the early 1980s. At this time, Sydney’s Blak arts scene was a grounding point that enabled Croft to flourish, becoming a founding member of the Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Cooperative in 1987, the longest running Aboriginal owned and managed arts organisation. These experiences established an ethos and intent that she would bring to a range of institutional curatorial roles and her own practice.

From 1999 to 2001, Croft was curator of Indigenous Art at the Art Gallery of Western Australia. Then from 2002 to 2009, senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art at the National Gallery of Australia, where in 2007 she established the National Indigenous Art Triennial: Culture Warriors.

She also contributed to international curatorial projects, including the 2006 Australian Indigenous Art Commission for the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris; and the Australian exhibition at the 47th Venice Biennale.

During this period, she continued to produce a significant artistic output, developing the acclaimed photographic series In my mother’s garden (series 48 photographs), 1999. In the 2015 essay ‘Say my Name’ she describes how:

“My approach to curatorial work was conducted in a similar manner to how I made art. I curated exhibitions of work that I considered was not well represented in existing exhibitions and much of my artwork could be considered as abstract self-portraits, in that I attempted to represent Indigenous people and their environs as a reflection of my own experience of exclusion or invisibility.”

Her desire to represent a peoples and culture that continue to be erased has a gravitas stronger now than ever. As she further described in the essay, “As a curator, I did not want to merely push against the existing boundaries but to overturn existing expectations.”

It’s an intention that she continues to forge in a growing number of leadership roles such as her recent appointment to the prestigious Gough Whitlam and Malcolm Fraser Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University, which she will commence in 2024. In a recent ABC radio conversation with Larissa Behrendt, Croft explained how she plans to establish further cross-cultural exchange programs while at Harvard.

It’s a process ensuring that more First Nations people in both continents have the opportunity to pursue scholarships and research at Harvard and ANU— where she is currently Professor of Indigenous Art History & Curatorship, at the Centre for Art History and Art Theory.

Whether global, local, familial or monumental, the work of Croft continues to push colonial boundaries while fortifying alliances and legacies both past, present and future. As she explains:

“My practice-led research entails elements of all that I have been, all that I am—creative and visual, observant and literary, representational and analytical. Whatever may await me, it must involve engagement with, and for, my community/ ies, whether in my traditional homelands, or as part of the Indigenous diaspora that lives in every part of Australia—be it metropolitan, pastoral or remote.”

In tenuous times the artistic leadership, vision and community-making that Croft has established will continue to create alternative pathways that strengthen First Nations sovereignty and belonging, beyond the limits of government speak.

National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards (NATSIAA)

Group exhibition

Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory (Darwin NT)

On now—18 February

This article was originally published in the January/February 2024 print edition of Art Guide Australia.