It’s quite strange that the opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 is also the year of greatest unemployment in Australian history. This conflicting juxtaposition, between triumph and troubled times, progression and dystopia, is what propels The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia’s show Brave New World: Australia 1930s.

Traversing painting, photography, video and design, the show aims for an expansive exploration of Australian life in the 1930s, surveying the new designs, technological advancements and growing engagement with the outside world from this period. As curator Isobel Crombie explains, “The 1930s in Australia isn’t the straightforward picture many people present it as; either art-deco or the Great Depression, where none of the complexities and juxtapositions are shown.”

Divided into themes, the show begins with ‘utopian cities,’ focussing on the progressive energy of urban development and women’s rights.

As Crombie points out, “At this time artists picked up on ideas of the modern city as optimistic and progressive, and part of that wass about the role of women, who were branching out from more traditional aspects of life.”

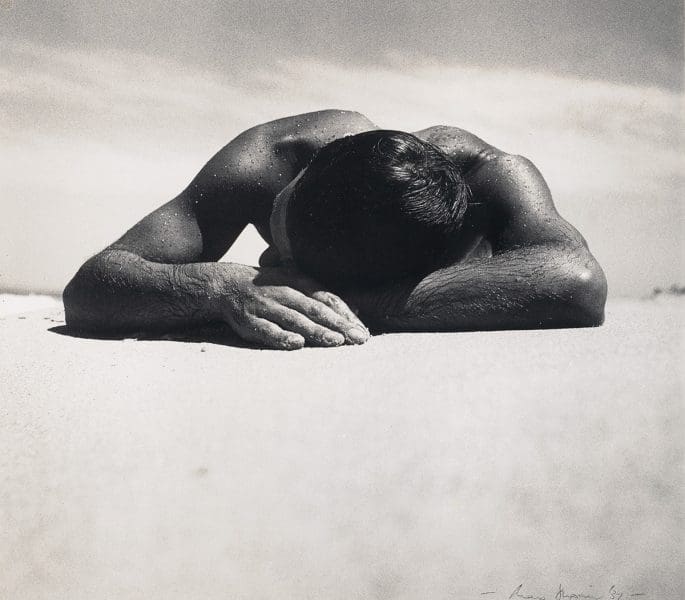

Yet it’s the body that sits as a pivotal site in Brave New World. “The body in the period was seen to symbolise a lot of the conflicting ideas of the time,” explains the curator. “It was a utopian form but it was also a physical form that was prey to a lot in the period; it was a force of optimism and degeneration.” This juxtaposition is shown through the works of Max Dupain, Charles Meere and Olive Cotton, as well as through a pair of stained glass windows (recently found in a local lifesaving club) showing a female lifesaver, a rarity for the time.

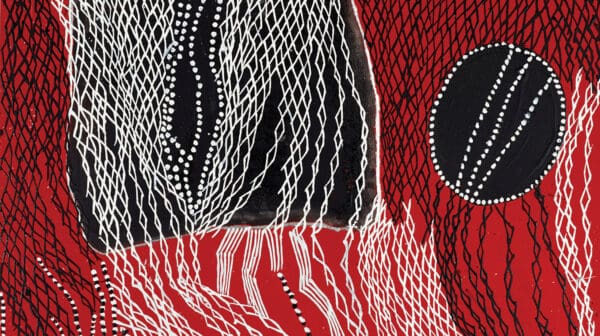

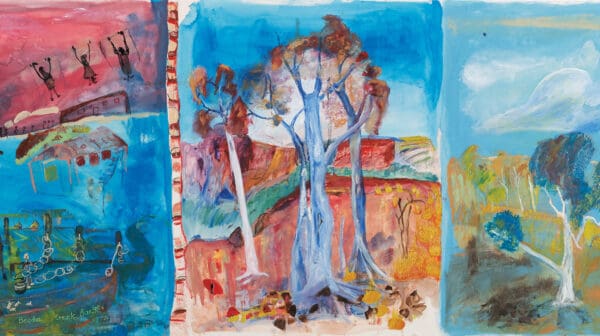

Another overarching (and much contested) theme is the Australian landscape. Crombie insists that “One of the great myths around this period is how the Australian landscape came to represent something intrinsically Australian; but of course generally speaking it was a white Australia.” Through the landscape, an emerging dialogue between conservative and modern art begins to play out. It also generated growing attention to Indigenous artists (Albert Namatjira held first exhibition during the decade) and the claim for land rights.

Considering that the title of the show is a reference to Aldous Huxley’s novel, there is clearly an unsettling aspect to the 1930s period.

This isn’t simply a reference to the Great Depression or being caught between two world wars, but also about questions of eugenics, the White Australia policy and national identity. “The conversations about eugenics are part of a global interest in how to form societies and Australians definitely engaged with those ideas, which you can see filtering through these works,” says Crombie.

Brave New World: Australia 1930s

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

14 July – 15 October