Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

The exhibition Sappers & Shrapnel: contemporary art and the art of the trenches is timed to coincide with Remembrance Day, 11 November. Curated by Lisa Slade, this powerful exhibition about not forgetting brings together the work of contemporary artists (including Tony Albert, Olga Cironis, Nicholas Folland, Brett Graham, Fiona Hall, Richard Lewer, Alasdair McLuckie, Baden Pailthorpe, Ben Quilty, Sera Waters and the Tjanpi Desert Weavers) with trench art from the collection of the Australian War Memorial. These works, both old and new, are essays in human acts of destruction and creativity.

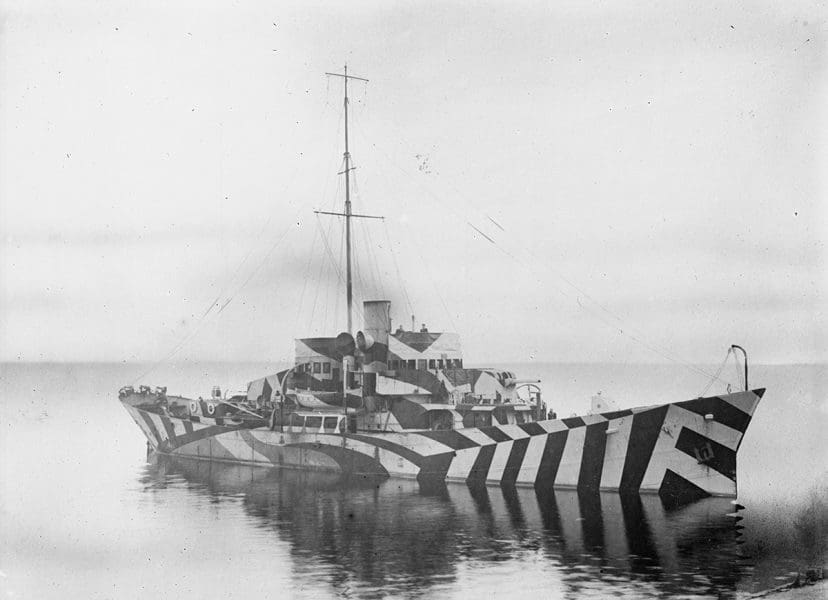

Trench art (especially works made by the prolific Sapper Stanley K. Pearl, a Tasmanian army engineer who fought in France during World War I) is featured at the heart of Sappers & Shrapnel. In Map of Tasmania, 1917, Pearl used a belt buckle that once belonged to a German soldier which bears the hole made by the bullet that killed him. Slade says this sort of work, made in the trenches of France from scraps of the everyday, “disproves the idea that art is a luxury, as creativity is expressed even in the most dire of circumstances.”

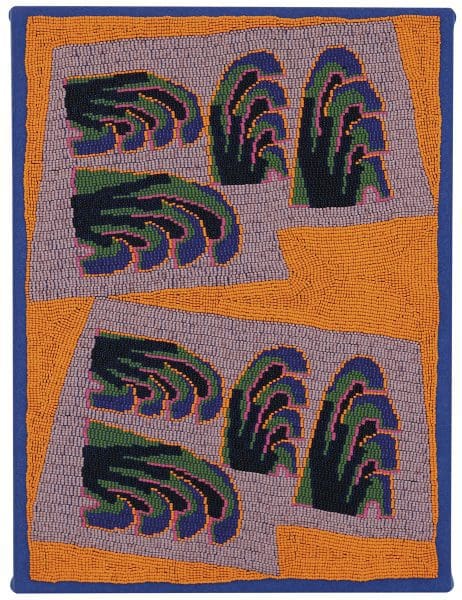

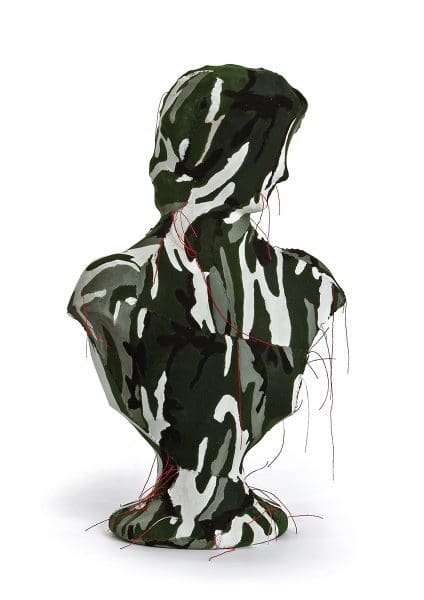

Sappers & Shrapnel also reminds us that conflict occurs in broader contexts than theatres of war. The Tjanpi Desert Weavers (Rene Wanuny Kulitja, Judy Ukampari Trigger, Erica Ikungka Shorty, Lucille Armstrong, Mary Katajuku Pan, Janet Inyika, Niningka Lewis and Freda Teamay) use camouflage military garments for Tjituru-tjituru, 2016, evoking the enduring anxiety of the dispossessed. Ben Quilty collected life vests, found on the beaches of Greek islands, discarded by Syrian refugees fleeing conflict. He pieces these together in Teeth, 2016, assembling the flotsam and jetsam of precarious lives.

It is surprising to find the waste of war repurposed as the stuff of art. The effect is often Dada-esque in its incongruity. Pearl transformed a German shell case into a vase, to “take a single flower,” according to the Australian War Memorial. Two more shell cases are used to make Alarm Clock, 1918, which is decorated with the Rising Sun badge of Pearl’s mate who died at Noreuil. Neither trophy nor souvenir, this clock marks instead, according to Slade, the everyday endeavour, even in war, to create.

This reappropriation of familiar items is also found in contemporary artworks. The vernacular becomes unsettling, as we consider the fragility of the everyday. Richard Lewer’s mixed media dioramas turn toy soldiers and doll houses into theatres of violence and desolation. The problematised familiarity of kitsch Australiana in Tony Albert’s work speaks to the diversity of the experience of war, and the failure of the nation to recognise the role of its Indigenous soldiers.

Trench art like Sapper Pearl’s, which has long eluded categorisation, is here presented by Slade as critical practice. This exhibition brings together works made from the shrapnel of a century of conflict, lest we forget the destruction of war and the endurance of creativity.

Sappers & Shrapnel: contemporary art and the art of the trenches

Art Gallery of South Australia

11 November – 29 January