The Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative has helped launch the careers of artists like Bronwyn Bancroft, Fiona Foley, Michael Riley, and Tracey Moffatt (who represented Australia at the Venice Biennale this year). Established specifically as an urban artists co-operative, Boomalli’s members have worked exhaustively to provide opportunities to Aboriginal artists both in Sydney and across regional New South Wales, and to locate and run exhibition spaces (they’ve moved several times). This has all had to happen in the face of the too-familiar, endless search for funding, so it’s not surprising that their 30-year anniversary show, The Boomalli Ten, exudes energy and pride. Showcasing the work of its founding members, the exhibition is packed with works from the 1980s up to the present day. The Boomalli Ten feels like a celebration not just of those 10 artists but more broadly of the Indigenous Australian art now flourishing in the post-colonial present.

Artists document their scene when they know something important is happening.

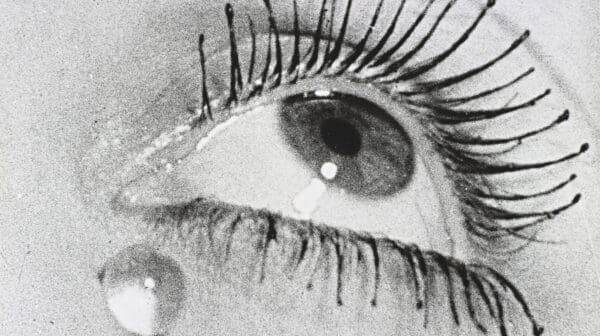

There’s a strong sense here of artists making their own history as they went. Michael Riley’s short documentary Boomalli: 5 Koori Artists, 1987, is at the literal centre of the exhibition. In fact, Riley is everywhere in this show which includes two works from his celebrated cloud series and two short films. His modest photograph Alice and Tracey, 1990, is a quiet refutation of past Indigenous representation. Referencing 19th century commercial and ethnographic portraiture in his unaffected portrayal of two women whose direct gaze meets the viewer’s, Riley both declares the primacy of Aboriginal self-representation and refuses to allow a single reading of past imaging histories.

Brenda L. Croft repeats something of this strategy and intent in her two commanding wet-plate self-portraits ABO.riginal and Mixed-blood, both produced in 2016. With a 26-year gap between Riley and Croft’s works, the ongoing quest for self-determination and expression that these works allude to resonates with the viewer, although the polemic tone of Croft’s work seems to be at odds with its poetic potential. Another striking self-portrait, Fiona Foley’s HHH#3, 2004, comically inverts tropes of white supremacist identity. Given the ugly images of far-right protests that have been filling our screens lately, this work stings the viewer with its continued relevance more than a decade after it was made.

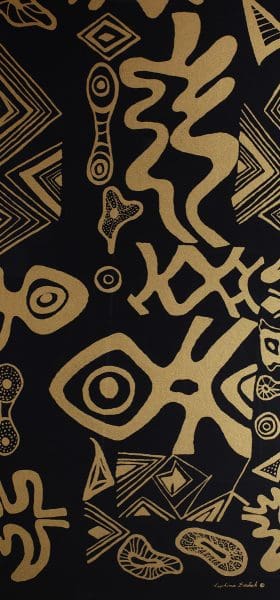

Printmaking, particularly screen printing, has always played a central role in many Boomalli artist’s practices. Euphemia Bostock’s print Possum Skin, 1986, and Spirit Ark, 2016, by Aron Meeks are lush examples. A work that demands to bust out of the gallery and become a commemorative street mural is the large collaborative painting by Blak Douglas, Joe Hurst, Djon Mundine, and Jeffrey Samuels, derived from Margaret Olah’s photograph of the original 10 Boomalli members.

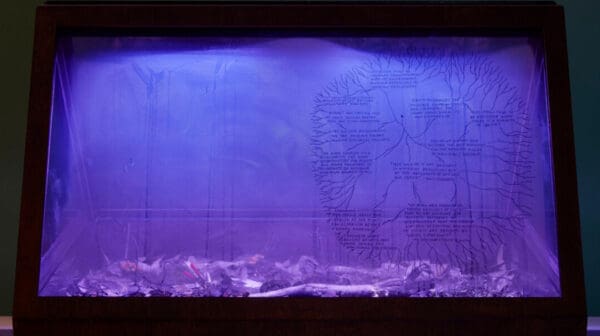

Lacking the resources of a larger, better-endowed institution, occasionally the presentation of The Boomalli Ten is less than slick.

Frustrating audio leaks and reduced audio-visual quality diminish the viewing experience of Riley’s and Moffatt’s important early films. Given the significance of this show, both Boomalli and the artists deserve better.

However, the sum of The Boomalli Ten is greater than its parts. Boomalli means ‘to strike or make a mark’ in the Gamileroi, Bundjalung and Wiradjuri languages. This diverse exhibition shows us the ripples Boomalli has pushed out to the lasting benefit of contemporary Australian art, and it recognises the Boomalli artists, curators, administrators and workers who have laboured for Australia’s cultural enrichment.

The Boomalli Ten

Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative

3 November – 28 January