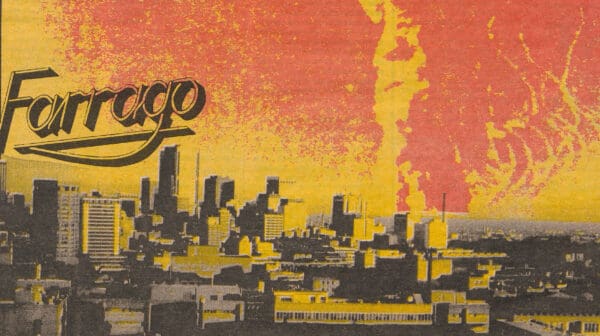

Farrago 100 years: Protecting Print Publishing

Farrago, the University of Melbourne’s student union newspaper-turnturned-magazine celebrates a hundred years of publication. At a time when print publishing in the arts is under increasing pressure, The George Paton Gallery is exhibiting ‘Farrago 100 Years’, celebrating the editorial legacy and design innovation of the periodical.