Piercing the veil

A new exhibition at Buxton Contemporary finds a rich complexity in the shadowy terrain between life and death.

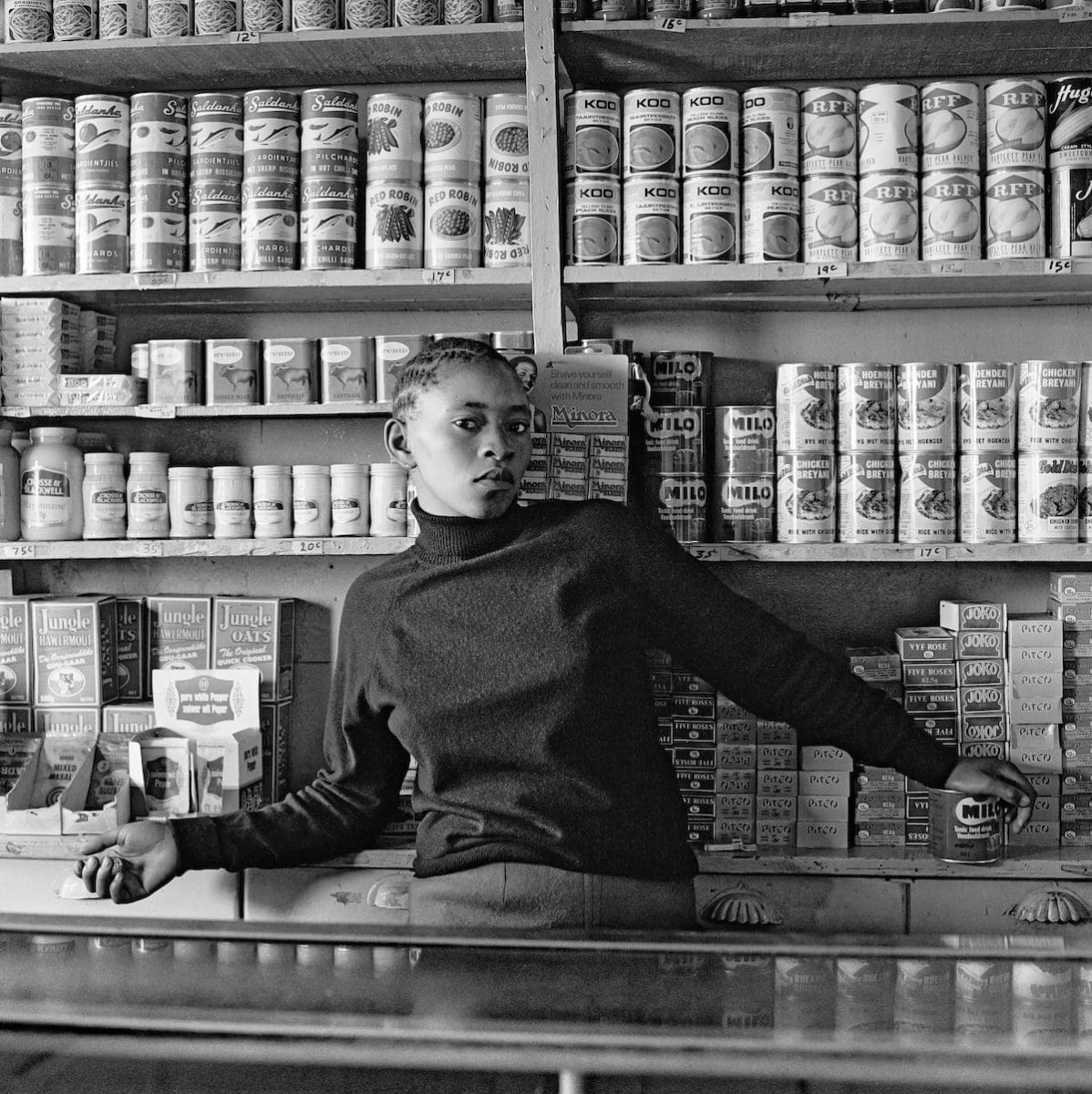

David Goldblatt, Shop assistant, Orlando West, 1972, 1972, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © the artist.

David Goldblatt, Blitz Maaneveld at the Terrace, Woodstock, Cape Town, where he murdered a man with whom he had been gambling. 7 October 2008, 2008, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town and Pace/MacGill, New York © the artist.

David Goldblatt, Young men with dompas (an identity document that every African had to carry), White City, Jabavu, Soweto, 1972, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © the artist.

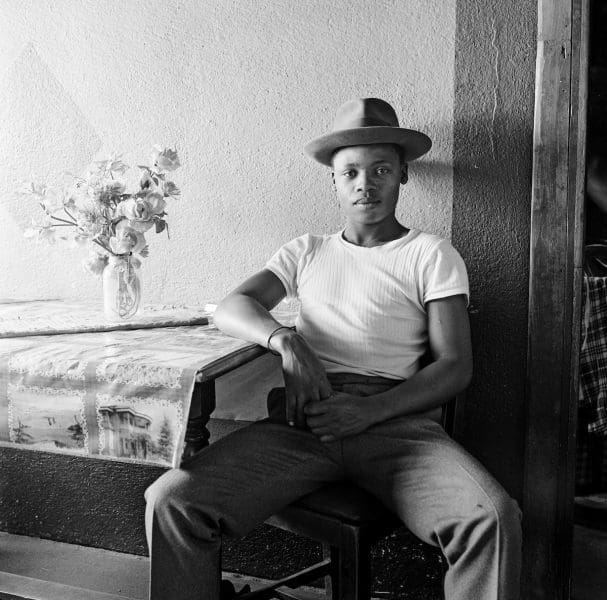

David Goldblatt, Young man at home, White City, Jabavu, Soweto, 1972, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © the artist.

David Goldblatt, Waitress, Bezuidenhout Park, 1973, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © the artist.

David Goldblatt, Patience Poni visiting her parents, Ruth and Jackson Poni, 1510A Emdeni South, Soweto, 1972, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © the artist.

David Goldblatt, Hold-up in Hillbrow, Johannesburg, 1963, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © the artist.

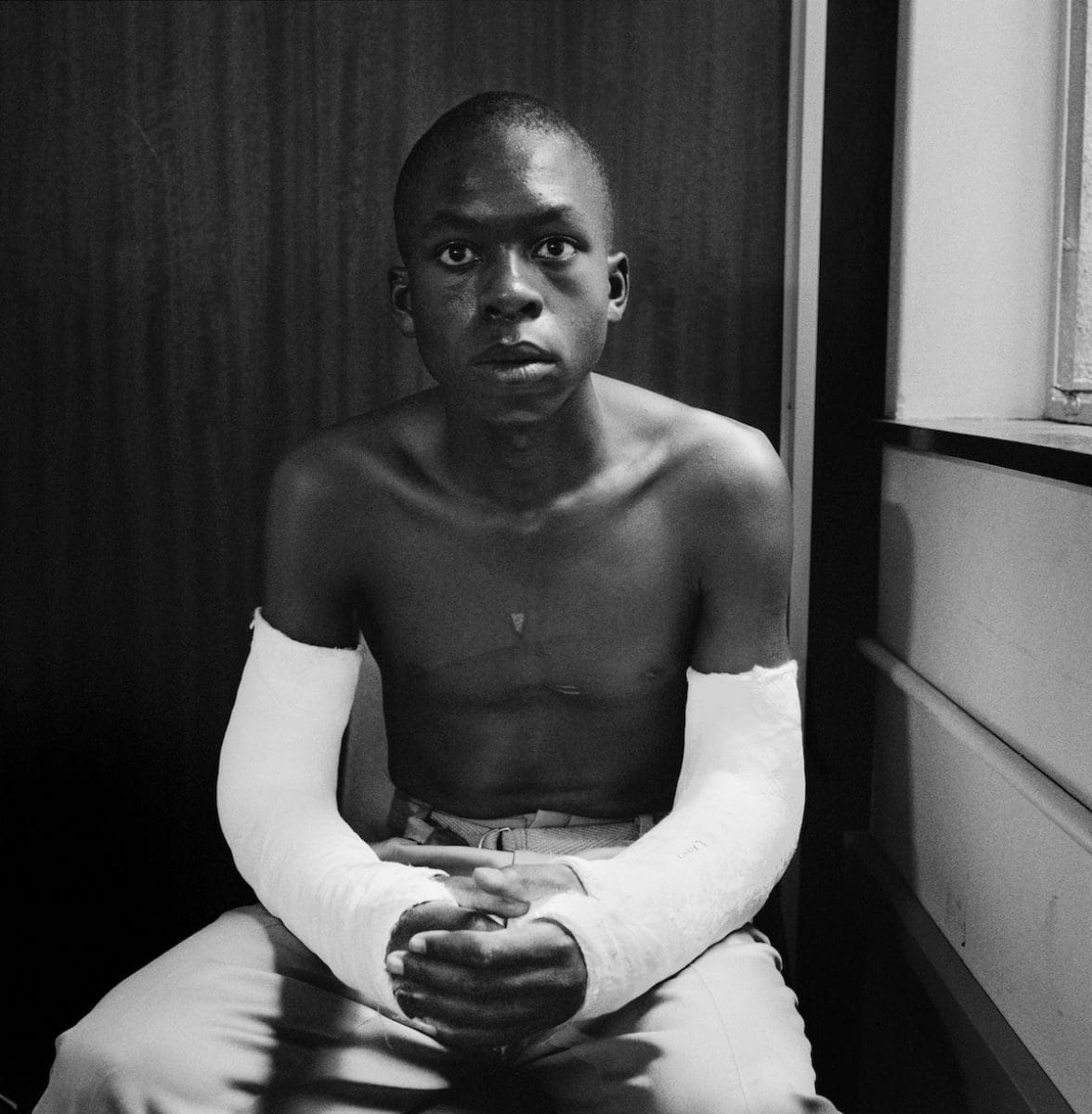

David Goldblatt, Fifteen-year old Lawrence Matjee after his assault and detention by the Security Police, Khotso House, de Villiers Street, 1985, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © the artist.

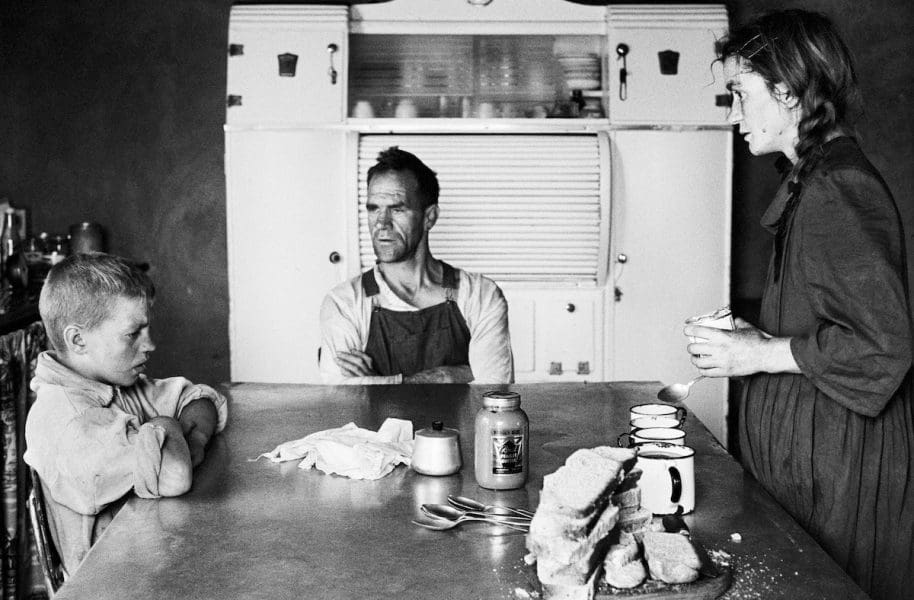

David Goldblatt, A plot-holder, his wife and their eldest son at lunch, Wheatlands, Randfontein, 1962, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © the artist.

David Goldblatt, Eyesight testing at the Vosloosrus Eye Clinic of the Boksburg Lions Club, 1980, silver gelatin photograph on fibre-based paper. Image courtesy the artist and Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg and Cape Town © the artist.

In early 2018 Rachel Kent, chief curator of Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, was working with South African photographer David Goldblatt to develop the largest retrospective of his work ever held in the southern hemisphere. Describing the experience as “a huge privilege,” Kent spent time road-tripping across South Africa with Goldblatt, taking in the landscape and landmarks that have informed his images. It proved to be one of his last trips as on June 25, just months before he was due to fly to Australia for the exhibition opening, Goldblatt passed away at age 87.

An unexpectedly timely exhibition, David Goldblatt: 1948–2018 spans the photographer’s lengthy career and brings together Goldblatt’s most significant works including early vintage prints and material from his personal archives. Best known for his portraits of South Africans taken throughout the four decades of apartheid, Goldblatt worked predominantly in black and white to create images of immense depth and compassion.

Born in Randfontein in 1930, Goldblatt was the grandson of Lithuanian-Jewish migrants who traveled to South Africa in 1890 to escape religious persecution. He was gifted his first camera by his brother in the 1940s and was deeply inspired by writers and the documentary style of American magazines, Life and Look. Maintaining his creative interests, Goldblatt went on to study at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg while his parents worked in the clothing business they owned. For a short period of time in the 1960s, Goldblatt worked with them before his father’s death led him to sell the business and pursue photography full-time.

Even before he began working as a professional photographer, Goldblatt was using his camera to document the people, architecture and industry that surrounded him. In 1948 the system of apartheid began in South Africa and Goldblatt was focusing his lens on the human side of racial segregation and its devasting effect, taking many portraits of people on the streets, in their workplace or at home. As a result, a significant portion of Goldblatt’s career and also the MCA exhibition, is his photographic documentation of South Africa under apartheid from 1948 to 1991.

One of these images is Goldblatt’s Young men with dompas (an identity document that every black South African had to carry), White City, Jabavu, Soweto, 1972. A major component of apartheid, the ‘dompa’ passbook contained fingerprints, photographs and information on a person’s birth, ancestry and employment. During apartheid, each of these factors determined how long individuals were permitted to stay in a certain area. In urban locations this was no more than 72 hours at a time, with failure to present a passbook resulting in immediate arrest and imprisonment.

MCA director, Elizabeth Ann Macgregor, believes Goldblatt’s practice “does not stray from the complexities of his country of birth but resonates with other global histories (including Australia’s own) through narratives of race and racism, and industry and the land.” Apartheid was in fact modeled on Queensland’s Aboriginal Protection Act of 1897, where large numbers of Aboriginal people were stripped of basic rights and forcibly removed to remote areas, much like the racial segregation implemented in South Africa.

The connection to Australia’s history also ripples through Goldblatt’s On the Mines series, a collection he began in the 1960s to document the dismantling of the mining industry near Randfontein. Spurred on by what these images revealed, On the Mines led Goldblatt to photograph the extraction methods of blue asbestos in the Northern Cape of South Africa and the after-effects of asbestos mining in the small West Australian town of Wittenoom. It also signified Goldblatt’s first foray into colour photography as it allowed him to depict the unnaturally vibrant blue of discarded asbestos tailings in contrast to the landscape.

Not far from the centre of Wittenoom was the site of mining company Australia Blue Asbestos. The inspiration behind the lyrics of Midnight Oil’s Blue Sky Mine, Australia Blue Asbestos closed in 1966 but remained at the centre of a monumental industrial disaster involving severe illness, multiple fatalities and environmental damage. As this was similar to what was occurring in the mining communities of South Africa, Goldblatt traveled to Wittenoom to add to his Asbestos series, further illustrating the ongoing damage caused by mining in two separate yet inherently connected regions.

Over six decades, Goldblatt amassed a vast collection of images documenting what was around him – the rise and fall of apartheid, the South African landscape and the lives of the people who lived there. Not an artist to shy away from difficult material, Goldblatt’s legacy is embodied within his ability to not only capture key moments in history through photography but to capture them with a palpable humanity.

David Goldblatt: Photographs 1948–2018

Museum of Contemporary Art

19 October—3 March 2019

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2018 print issue of Art Guide Australia.