Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

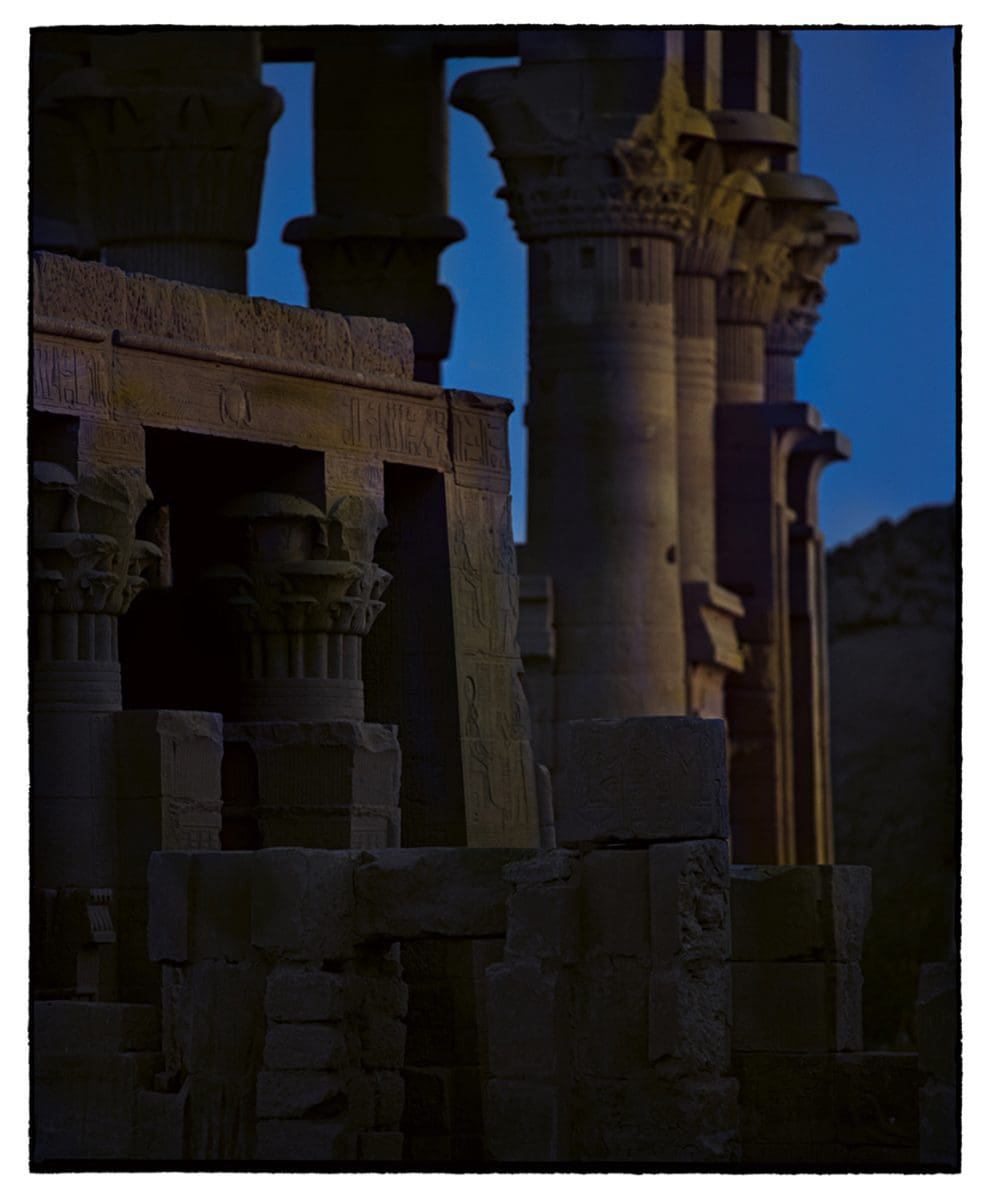

The light fades but the gods remain, the new Bill Henson exhibition at Monash Gallery of Art (MGA), Melbourne, opens with a pairing of opposites. As you enter the exhibition, Untitled 42, 1985-86, a photograph of a suburban house with a front lawn at either dawn or dusk, is to your right. To the far left is Untitled 86, a close-up of ancient Egyptian ruins. Between these two extremes of human habitation, there lies a tension – a tug-of-war between past, present, future, and also between here and there.

The exhibition features Henson’s series Untitled 1985–86– informally known as ‘the suburban series’ – and a new body of work commissioned by MGA for its 25th anniversary, Untitled 2018–19. Before being commissioned to create this series, Henson has had a long history with MGA having exhibited at the gallery, served on its board, judged the Bowness Prize (the annual photography prize associated with MGA) and curated exhibitions.

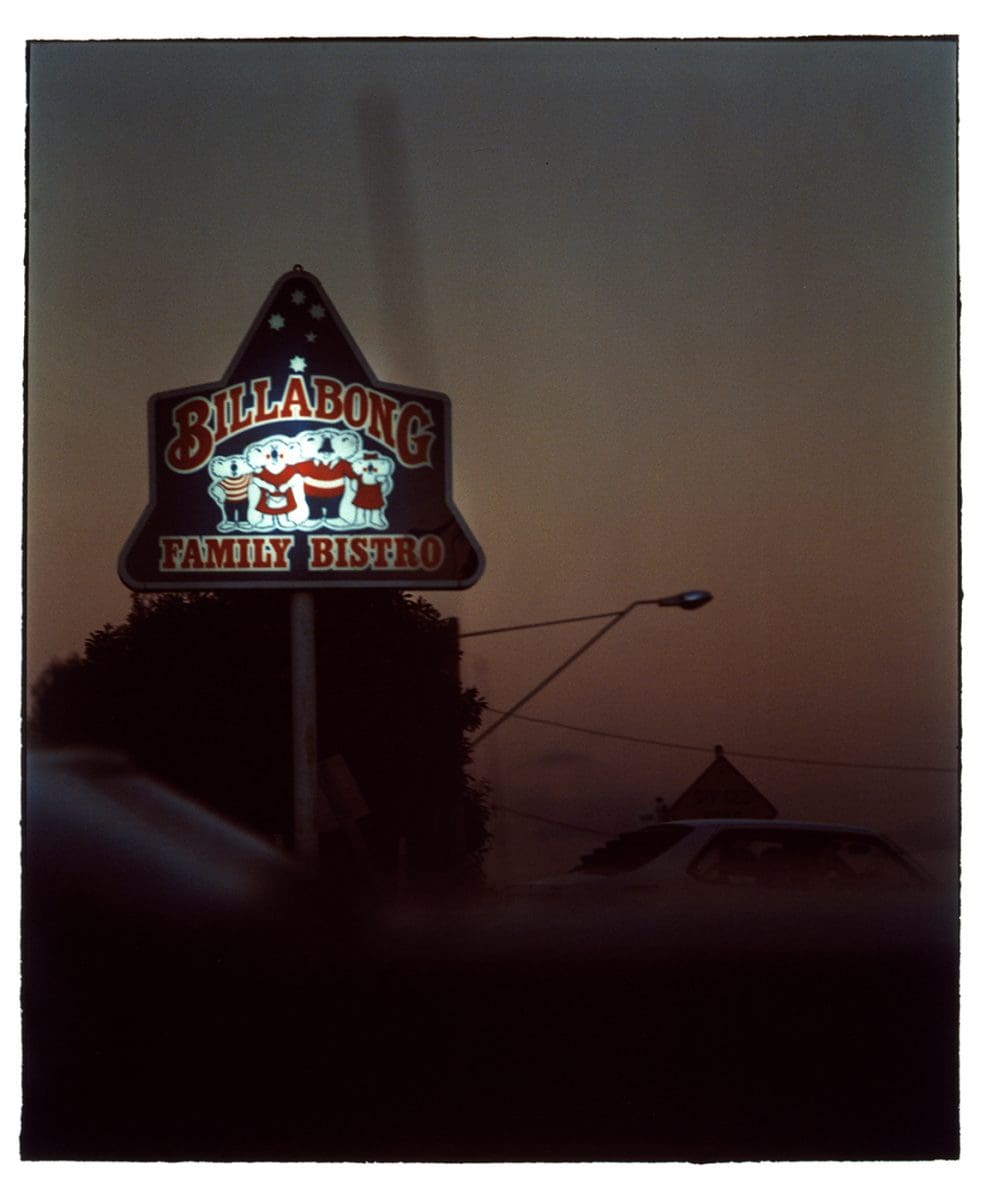

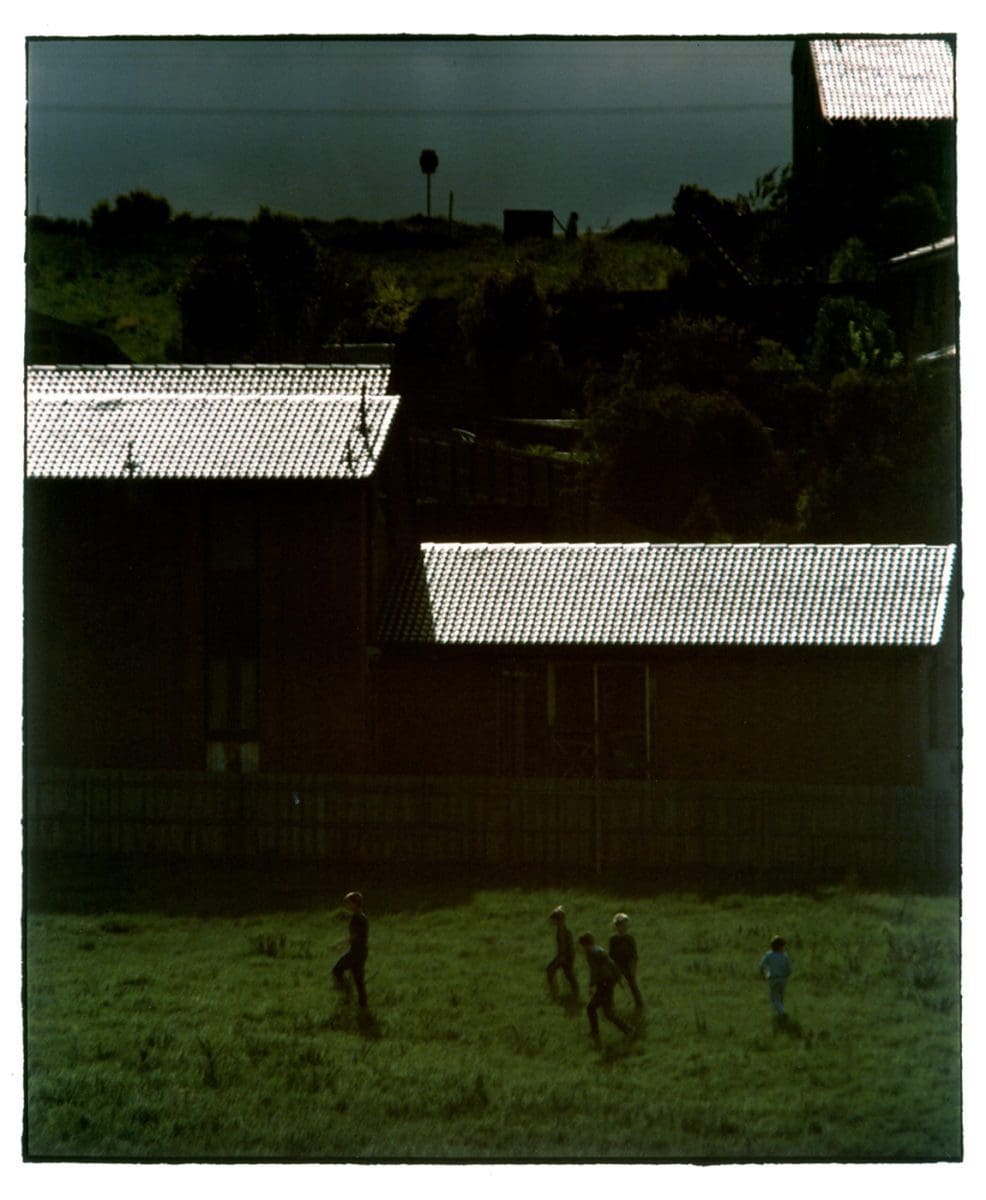

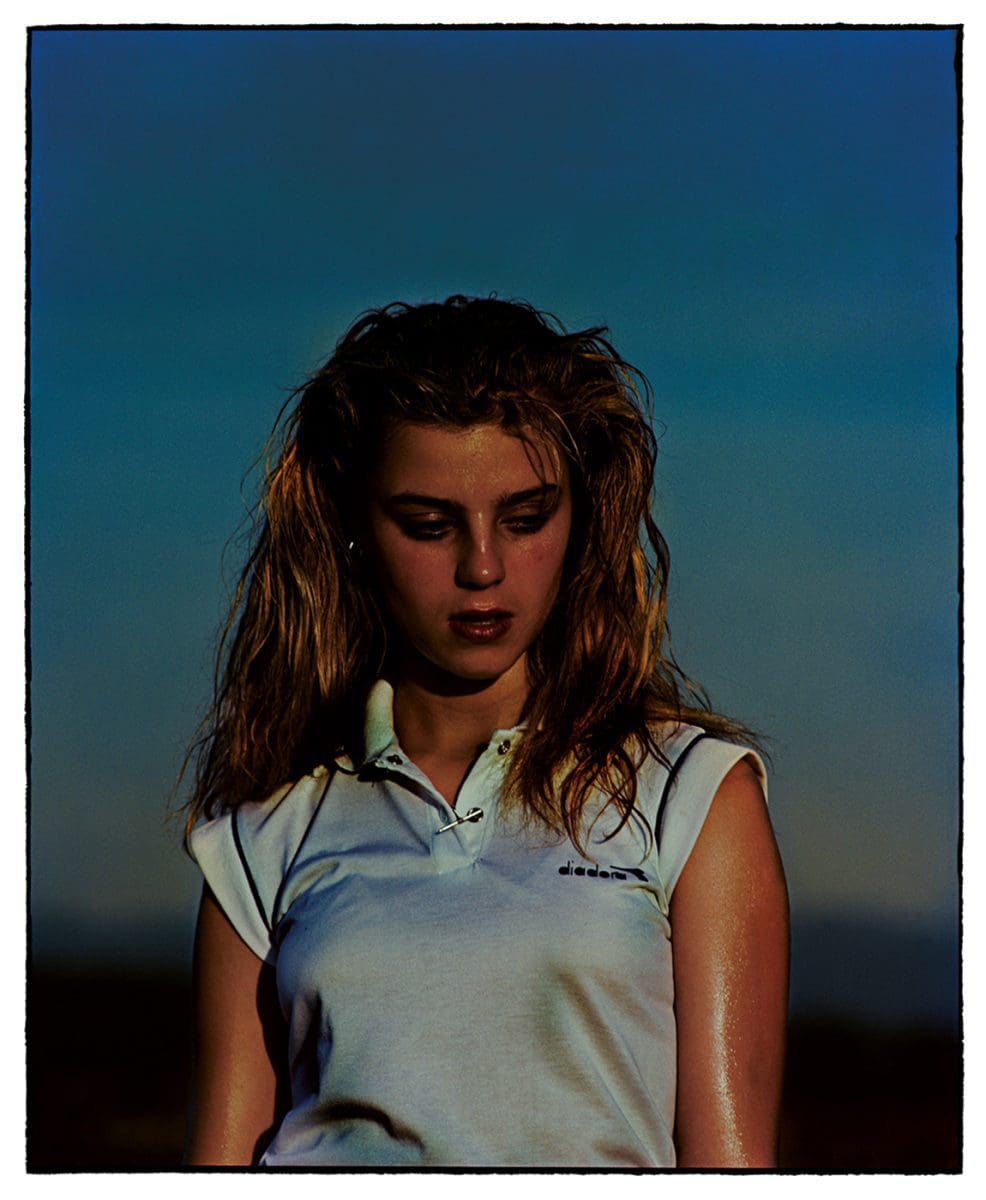

In The light fades but the gods remain, Henson’s old and new works are exhibited in two separate, but connected, rooms. The first space is painted dark but brightly lit, and features photographs from the aforementioned ‘suburban’ photographs. The series is a beautiful, moody and sombre visual meditation on Glen Waverley, the Melbourne suburb where Henson grew up, not far from MGA.

These photographs have been exhibited in numerous configurations since their very first showing, but this concise curation of the series features groupings of mostly two or three based on shifts of light, colour and tone. In this selection of just 21 works from the 154 that make up the series, the photographs, which measure around a metre wide, have been given plenty of room to breathe.

Sandwiched between scenes familiar to those who grew up in suburbia – the family bistro in Untitled 73, the glow of a Mobil petrol station in Untitled 76, the cluster of roofs in Untitled 31– are images of ancient Egyptian ruins, as well as scenes of children playing and the intimate portraits that Henson is renowned for.

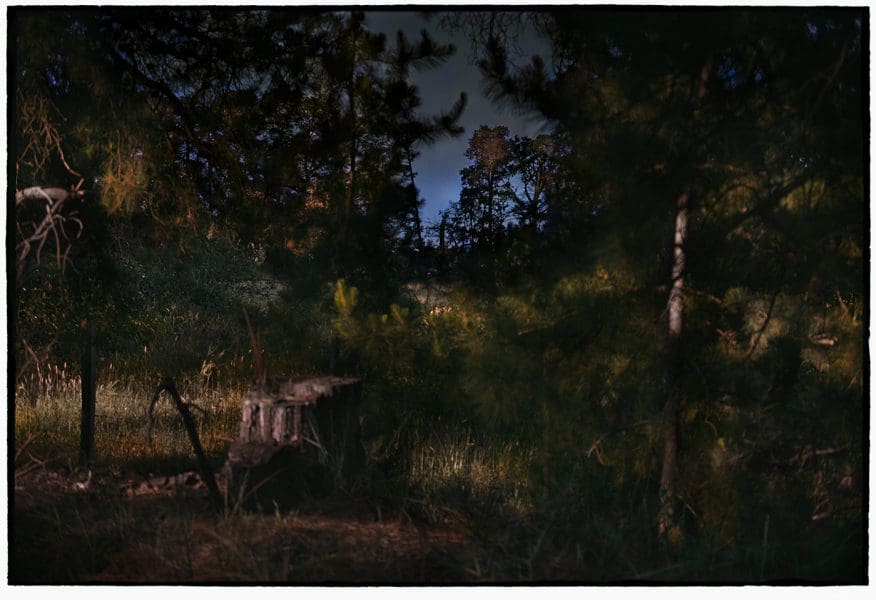

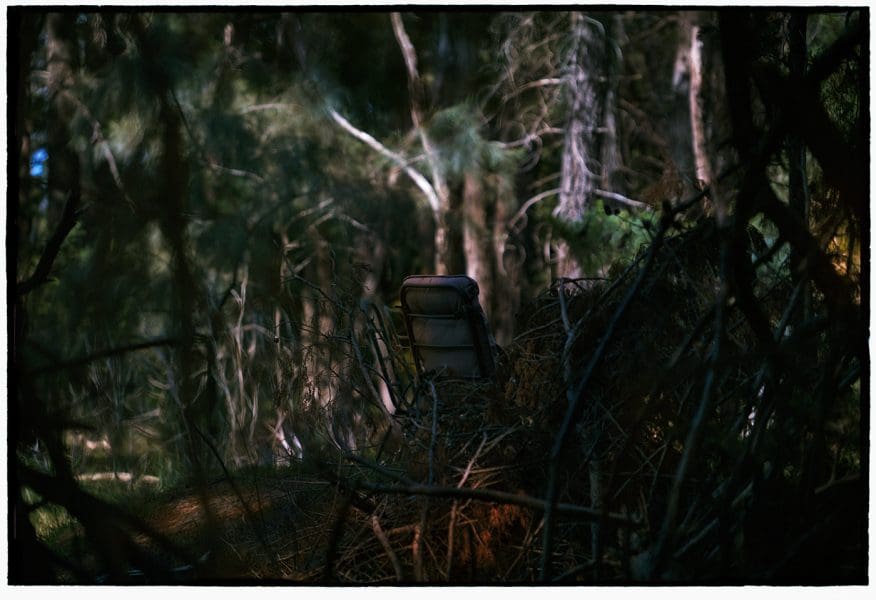

In contrast, the 11 photographs from Untitled 2018–19 that feature in the exhibition only bear traces of human habitation: chairs obscured by the bush/scrub in Untitled 9, fuzzy hints of houses in the far distance in Untitled 10.

Instead of revisiting the suburban series 30 years later, Henson has visited suburban peripheries – the places beyond the picket fences, places that once upon a time may have symbolised dreams and escapes. These scenes are hazy, their focal points a little unclear, indicating Henson’s absence from here all these years. It’s a return to ‘home,’ to the place where he grew up, but carrying the heavy sediment of time with him.

As in the first room, this second gallery space has also been painted black. These large works have again been given ample room to breathe. But the lighting is a little dimmer, a little softer (the brighter lights in the first gallery space detract a bit from Henson’s moody tones). And here, a lone bench in the middle of the room invites speculation on the fragility of memory, of hopes and dreams, of time and history.

The light fades but the gods remain

Bill Henson

Monash Gallery of Art

27 July – 29 September