Making Space at the Table

NAP Contemporary’s group show, The Elephant Table, platforms six artists and voices—creating chaos, connection and conversation.

The first time I interviewed Ben Quilty I had to convince the magazine I was writing for (not this one) that he was worthy of a profile piece. I talked them into it, but they only gave me 500 words. This was 2008, before he won the Archibald Prize and became an official Australian war artist, before Ben Quilty became a media sensation. Times certainly have changed.

These days you almost can’t turn on the telly or open a newspaper without catching a glimpse of Quilty. In the weeks leading up to this, our third interview, the artist was featured in The Guardian, The Sydney Morning Herald, Art Net News and on Julia Zemiro’s Home Delivery on ABC TV. And there were probably more appearances that I missed.

We are meeting at CarriageWorks where Quilty is about to present at the glitzy 2016 APRA music awards. I put it to him when he arrives (looking, if not exactly red-carpet ready, like it won’t take much to get there) that he is everywhere.

He concedes that it’s true and admits that he has to turn things down all the time now. “It’s bizarre,” he says. “Ten years ago I couldn’t get a show in Sydney anywhere.” Actually, ten years ago, almost to the day, his first solo show at Sydney’s now defunct Grantpirrie Gallery closed. It was a sell-out affair (if I recall correctly) that featured massive portraits of his old white van morphing into a skull. But I’m not about to quibble. The point is, a lot can happen in a decade.

In fact, a lot can happen in an even shorter amount of time. It was the work he made when he back got back from his 2011 stint in Afghanistan as an official war artist that really catapulted him into the full glare of the media spotlight. His show, After Afghanistan, toured the country until April this year and something about his paint smeared portraits of Australian soldiers (nude, vulnerable and painfully human) touched a nerve with the wider public.

Which is not to say that Quilty doesn’t have his detractors. Australians love nothing better than lopping the heads off tall poppies, it’s a persistent cultural trait.

In 2015 Quilty was nominated for Australian of the Year as an artist and human rights campaigner. I ask him if this was a conscious decision, did he just wake up one day and decide to add human rights campaigner to his job description? “No way,” he says. “I was just standing up for my mate.” (The friend in question was convicted drug trafficker Myuran Sukumaran who was executed by an Indonesian firing squad despite the best efforts of Quilty and many others.) Quilty didn’t win the accolade but the label stuck. He is both an artist and an activist. And he’s done apologising for it.

“At school I never thought I’d admit that I was an artist,” he explains. “Later, when I became an artist, I never admitted that was what I did. And now I think, bugger that. I am an artist and it’s really important that some of us are doing it, against all the odds, against absolutely zero support from the broader society… I do have things that I want to say. And I don’t really take the backward step of feeling guilty about that.”

For Quilty, it’s important that artists weigh-in on social issues, travel to war zones, stand up for citizens on death row. Because artists, while observers, do more than just record. “We are meant to go and look at something and come away and respond to it. And that’s why it’s so different to journalistic practice as a visual language,” he says. “What we make is a reaction, so we can engage in so many different ways. We can bring our life experience and our philosophy into play, and actually create dialogue about that situation… So that is why it is so powerful that artists are given these opportunities. Because that’s what we are meant to do, I think. And given those opportunities, I can’t say no. Not when they are so big and profound and I feel like I am watching history moving in front of me. No way.”

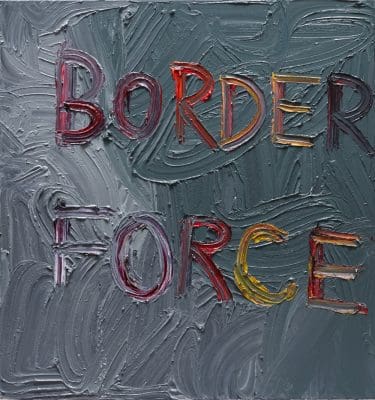

Quilty’s latest opportunity was a World Vision sponsored trip with the writer Richard Flanagan. In January 2016 they travelled together to Syrian refugee camps in Lebanon, Greece and Serbia in order to raise public awareness about the scale of this ongoing crisis. Quilty returned with a renewed sense of the triviality of “first-world problems” and the injustice of Australia’s treatment of refugees, a policy which he describes as barbaric and lacking in foresight.

Looking to the future it seems obvious to Quilty (as it does to many of us) that the current tide of refugees heading to our shores is just a trickle. The real deluge will come as global populations continue to increase and environmental calamites force mass migrations. “And,” Quilty says with both exasperation and disgust, “we are already freaking out about refugees who are coming legitimately because we started a fire storm in Iraq.”

Instead of sheltering behind what Quilty calls our “natural wall” and a cruel xenophobic refugee policy utterly lacking in human compassion, the artist hopes that we can begin to “engage in a proper, serious, deep political debate.”

For Quilty this means making artworks that highlight the issues, but it also means actually talking to politicians. After all, as he points out, they are the ones who make the policies that form our country. “And I want to be in that debate,” he says. “I am really lucky to have a voice. It’s a huge privilege. And there should be more artists doing it.”

Quilty is highly critical of current governmental policies. Citing as examples the refusal to sanction same sex marriage, the closing down of art schools and the incarceration of refugees, he says, “We have a serious lack of leadership at the moment.” But Quilty hasn’t given up on Australia. He is very proud of the fact that next year is the 50th anniversary of the last time the death penalty was used in Australia. It didn’t happen in his lifetime, but this change still gives him hope. “We have the foundations of a brilliant contemporary society,” he says. “The bricks are just cracking at the moment. And with guidance, and the right people standing up, it will find itself again.”