Finding New Spaces Together

‘Vádye Eshgh (The Valley of Love)’ is a collaboration between Second Generation Collective and Abdul-Rahman Abdullah weaving through themes of beauty, diversity and the rebuilding of identity.

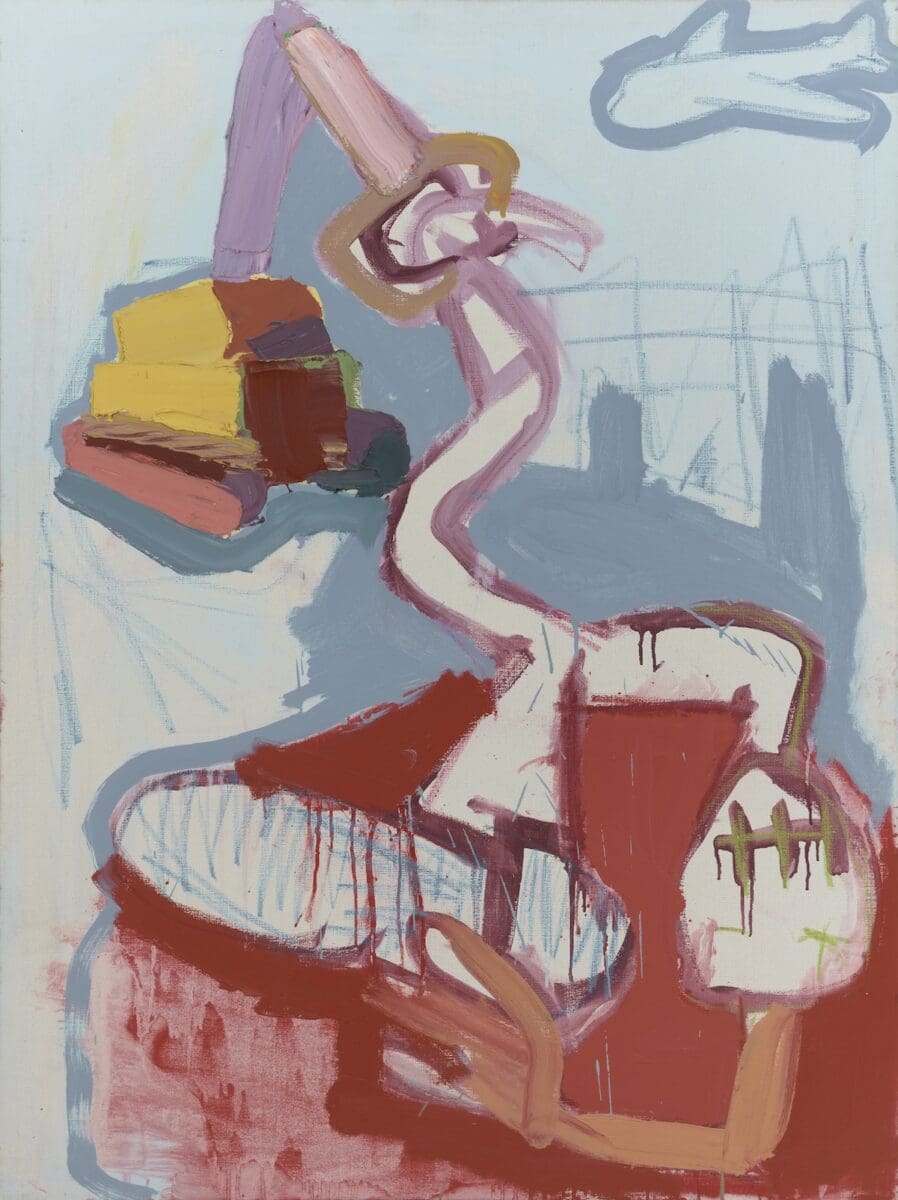

Ben Quilty, Homeland, 2014, oil on linen, 202 x 265 cm.

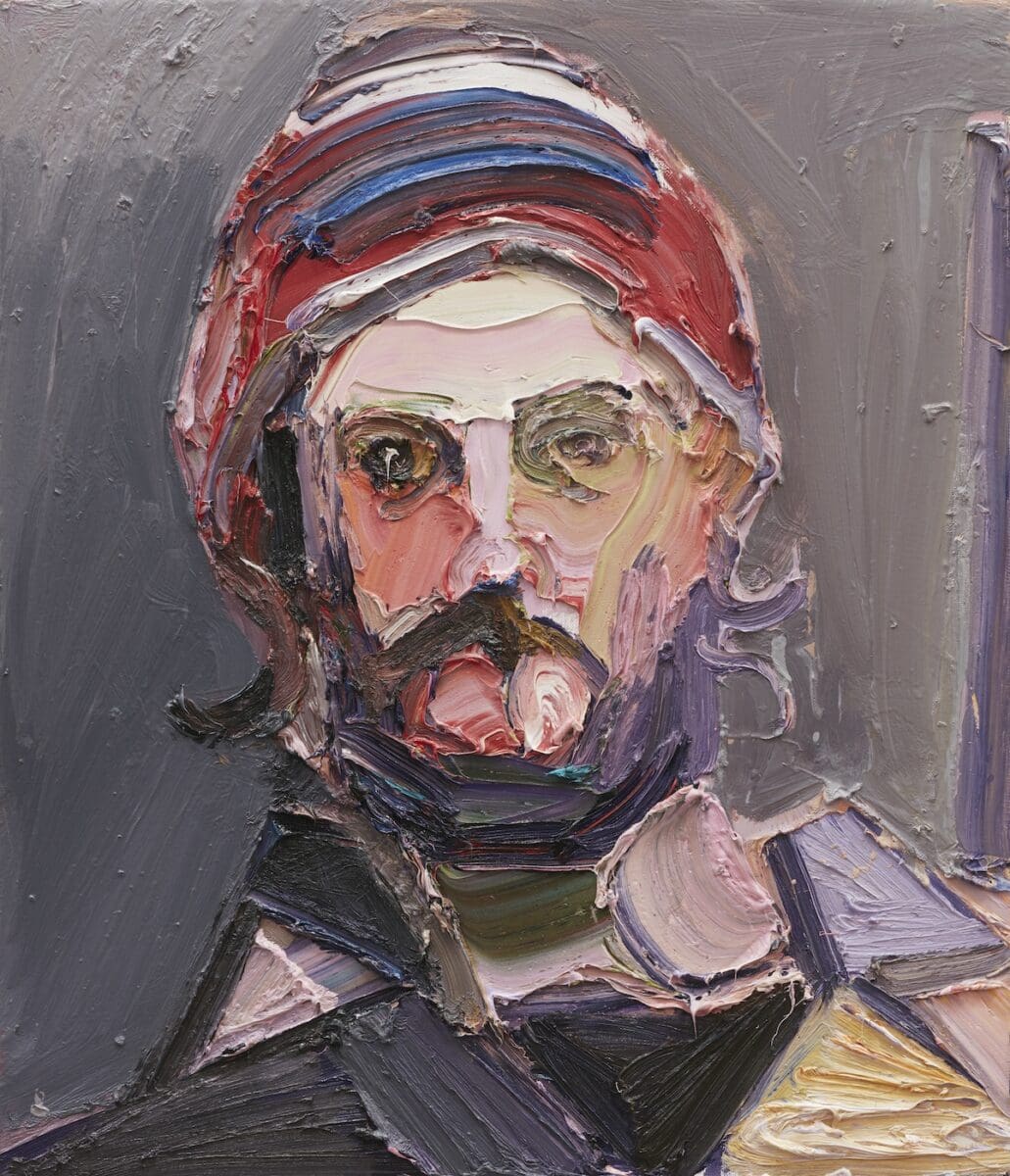

Ben Quilty, Self After Injury Study, 2018, oil on linen, 71 x 61 cm.

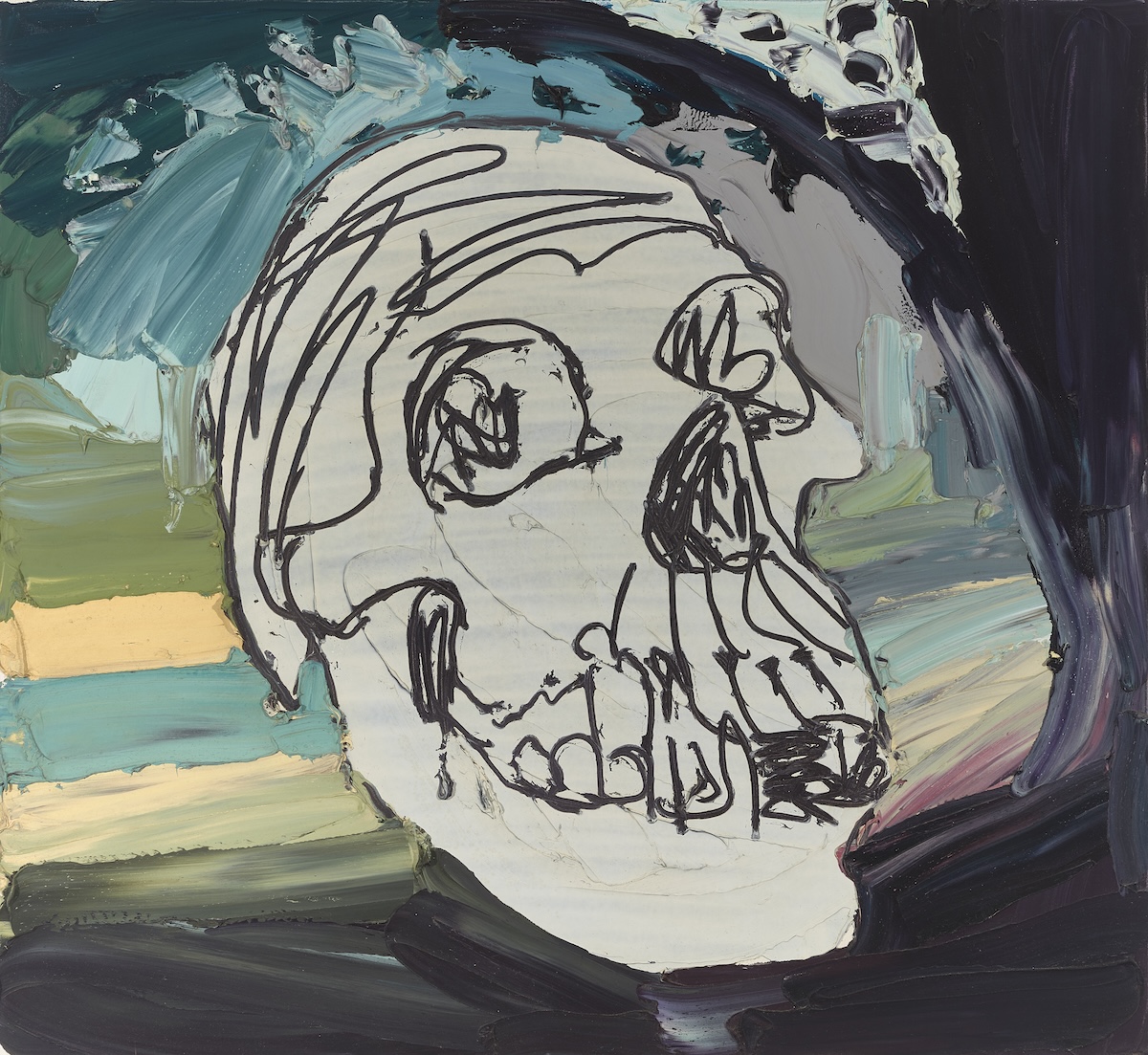

A Torana’s crumpled bonnet. The haunted gaze of a soldier. Skulls and Rorschach blots done in a thick, bruising impasto. The signifiers of a culture shaped by undercurrents of violence and a white, male psyche at war with itself have animated the paintings of Ben Quilty for the last two decades. Here, Quilty—the subject of Ben Quilty: 20 Years, an upcoming retrospective at Jan Murphy Gallery—talks to Georgia Spain about the wrestle with mythology that has defined his career. He also shares, with his fellow painter, the contradictions of joy and suffering and a belief in art as an antidote to an increasingly volatile world.

Georgia Spain: Tell me Ben, what have you been working on?

Ben Quilty: I’m about to go to Korea with Jan Murphy Gallery for a two-person show with Betty Muffler. I’m a huge fan of Betty’s. I’ve just been to her homeland Indulkana and art center, Iwantja.

Betty’s one of the senior people in that community. Jan wanted to put us in a show together and I couldn’t do that without at least contemplating a way of responding to Betty’s work. There’s Betty with 60,000 years of accumulated cultural knowledge, and here’s me with 160 years in Australia, and unknowable Irish DNA in my blood. I’m making more and more works that are delving into Catholicism from when I was a kid and the violence of that kind of upbringing. And how we create these myths and figureheads as a way of hiding from the fact that we don’t have a thousand years of accumulated cultural knowledge, let alone 60,000 years. So, I made a series of gnome paintings. The gnomes will just be a salon hang—almost like some colonial trophy wall of gnome heads. Then, in the other part of the space are these massive, mesmerisingly mythical paintings by Betty Muffler.

GS: They’re both tied to ideas of mysticism and myth. But like you say, we have so little to grasp onto that we try clinging onto anything. It’s like, gnomes—that’ll do!

BQ: Yep that’ll do, that’s all we’ve got.

GS: They’re flimsy myths and there’s something comical about that too.

BQ: Yes, like Santa Claus. Santa’s this massive big bloke who smokes a lot of cigarettes and breaks into kids’ rooms in the middle of the night. There are ways to read the mythology around that Christian event. It’s mad.

GS: Your work is humorous but it also carries a darkness and grittiness.

BQ: Thanks. Well, you and I are using paint to try and pose similar questions. I think that’s what drew me to your work at the beginning, that it felt like you were exploring. And without that cultural background, it’s an eternal search. I remember in the 90s, there was this big move to Buddhism, and then [the next decade] we see Buddhist monks running through refugee camps in the Rakhine State killing Rohingya people. I think with such short tracks on the planet culturally speaking, we are searching for something to cling onto. And you and I have painting. There [are] no rules, no guidelines. We can go anywhere.

GS: Yes, there’s this endless well of things to draw from: the turmoil, the anguish, the pain of the world. It’s overwhelming at the moment. It’s everywhere you look. That’s something I think about in my practice. How can I use painting as a way to process that?

BQ: At the end of the day we’re just trying to get ideas out of our head about who we are and how we feel about being alive on the planet. And for you and I, it’s very much within the boundaries of having this really short cultural and national genetic identity. So, what are we saying? How are we responding? We can’t tell people how we think, unlike Betty Muffler, who has the most profound way of communicating her understanding of who she is. I think that explains the mad fight for a search for our own identity in the West, because we are so brief.

GS: Many of your paintings [feature] images of fighters. That’s a recurring motif in your work. Do you struggle with the act of painting? Does making paintings have to feel hard?

BQ: The harder it is the better they become. And really, hard in what context? We’re not living in a Rohingya refugee camp. For some reason our community has a lot of mental blocks around creativity. I think the notion of a ‘practice’ is an attempt to overcome all of that. It’s just turning on a tap rather than having to navigate writer’s block, which is all made-up rubbish. We’re alive and we’ve got access to coloured mud and a brush. So, go for it and find the confidence to just pour out your ideas. The biggest part of that is not being worried about making a mistake.

GS: And to not worry what anyone else really thinks about it?

BQ: That’s the most important thing. And then it becomes as close as you can get to a spiritual pursuit, like a religious pursuit. You and your “God”, you know? It’s powerful.

GS: It’s a powerful medium. Your paintings communicate who you are, they’re undeniably you. I think that extends to everything we make as artists, that we can’t escape or hide from who we are.

BQ: Yes, and yours too. But we’ve got to push it outside that. It’s so easy for that visual language to become the most important thing in a painter’s practice. You can get stuck in that. It’s like handwriting and your handwriting’s neat so then you just keep writing neatly. If I’m in a comfort zone, then I’ve got to get out of there.

GS: How do you personally do that? Do you set yourself parameters?

BQ: I change materials often. I’ve been working in acrylic recently, which I find mind-blowingly difficult. It’s just not got the lustre. There are so many different ways of working—using ink or making sculpture. I’ve just made a bronze with oil-based clay. Then, when I come back to paint it always feels like I’ve reinvigorated something.

GS: I know you have a deep commitment to having a routine and structure around your practice. Is it a struggle to find the right balance with the other important things your life?

BQ: Well, there’s nothing I want to do more which makes it easy to have that practice so rigid, but it fits in around other people. There are three people in my home, and I have to fit around them. I don’t work into the middle of the night. I probably did a lot more late nights before we had kids.

GS: You’re not afraid to tackle the ugliness of the world in your work. You don’t paint pretty things for the sake of painting pretty things, right?

BQ: What’s the point of that when the most vulnerable humans are being decimated and I have Indigenous friends who are living with the greatest social inequality? There’s too much to talk about. There’s too much to make work about and a lot of it, for me, comes from anger, in the sense that injustice really boils me. And through painting you’re responding to something in a far more measured way than social media. You’ve got to go through a process, and it takes weeks, if not months or years to actually respond. It’s a far more sophisticated way of responding.

A lot of the work I’m making at the moment is about climate. About how, for example, Australia’s become the dumping ground for huge V8 cars. Most other countries have realised that encouraging self-indulgent burning of fossil fuels is going to kill us all. And yet we have more of them than most other countries on the planet. There is so much to make work about.

GS: Is painting always a place for letting out that anger, fury, rage?

BQ: I’m probably a much happier person because I have an outlet for that anxiety and anger. I think now in 2024, we’re more aware of what’s happening all over the planet. Whereas a hundred years ago, people were living in blissful ignorance.

GS: It’s a blessing and a curse, I think, having access to everything. The constant reminder of the paradox that joy and suffering exist simultaneously.

BQ: I recently went down a bird flu rabbit hole about what was going to happen to several threatened bird species, particularly black swans in Australia. My phone just keeps feeding me this stuff. Now [that] we have these phones where we can look at anything anywhere in the world right now without moving, it feels like a lot of us have become more parochial. We have access to everything and seem to look inward more than ever.

GS: How do you stay optimistic about the future of the world?

BQ: I’ve been criticised for being pessimistic in the past. I am very aware that we’re a tiny blip in the universe and I have spent a lot of time camped out with people who have pretty profound understanding of how they fit into the universe. Most of my work is about humans, so it’s never going to be really pretty. But I like being human. I love being a dad. I love my kids. I love [my wife] Kylie. I love being alive, and spending time in my studio is such a privilege. At the same time, I want to make a difference. I want to stand up for stuff. I’m never going to stop doing that.

Ben Quilty: 20 Years

Jan Murphy Gallery

19 November—7 December

Twitcher

Maitland Regional Gallery

On now—16 February 2025

This article was originally published in the November/December print issue of Art Guide Australia.